Loose Credit, Rust Belt Woes Lead to Foreclosure Uptick

Shutterstock

Connecting state and local government leaders

Beyond the Rust Belt in some of the high-flying real estate markets in cities like Denver and Austin, the rare increases in foreclosures may be early warning signs of trouble ahead.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Tim Henderson.

Foreclosure starts have begun to edge up in some of the nation’s hottest housing markets, an unsettling development that worries some economists.

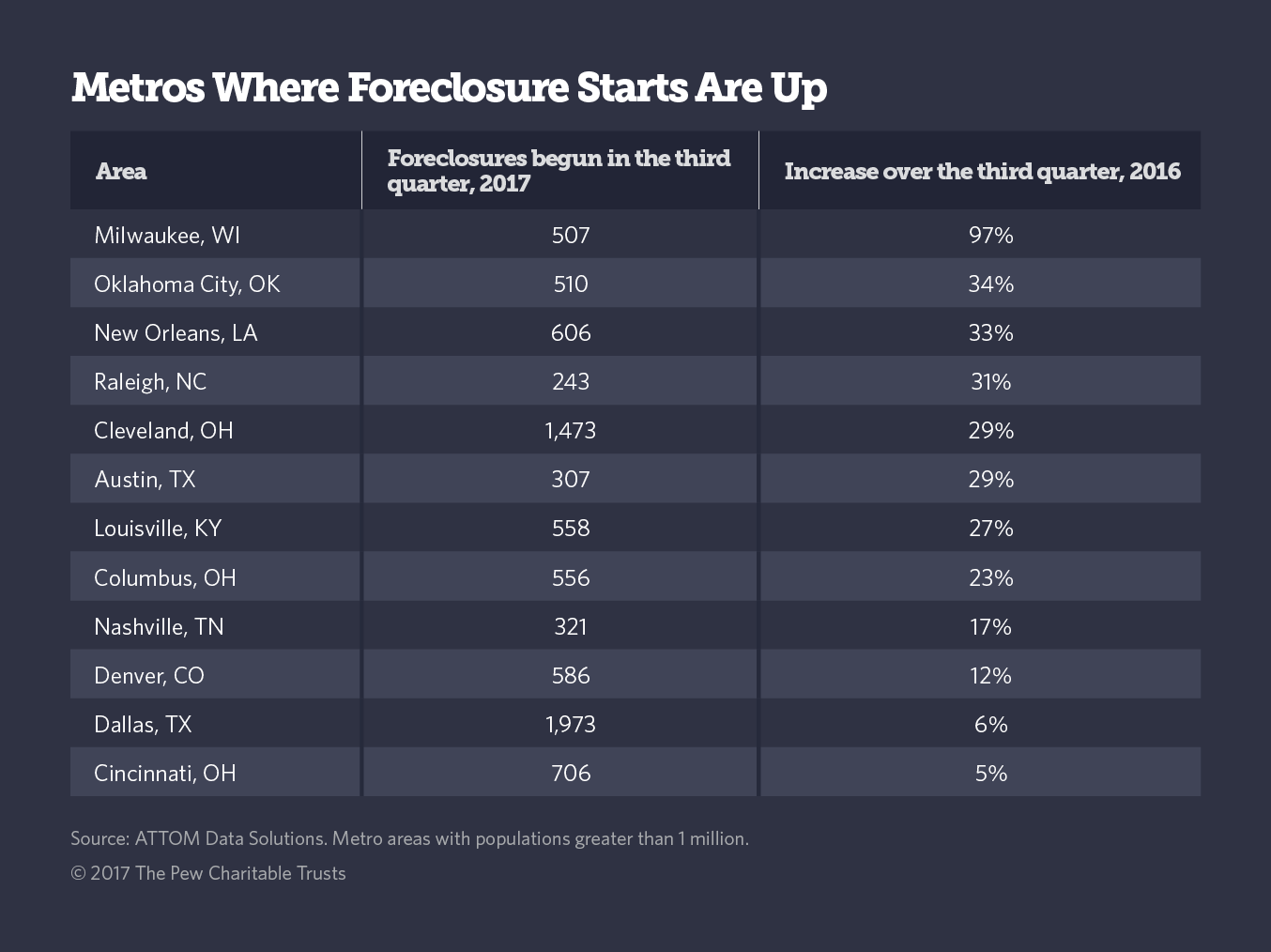

Nearly a quarter of the nation’s large metro areas saw upticks in foreclosure starts, the point when banks take the first step to foreclose on a delinquent home loan, in the third quarter of this year. That included a surprising number of some of the hottest inland housing markets, such as Denver, Austin, Dallas, Nashville and Columbus, Ohio.

The apparent causes are varied—a heartland affordability crisis, underemployment for many in the middle class, banks that offer loose credit and low down payments, debt-stricken retirees—but experts fear rising foreclosure rates could spell trouble for roaring housing markets in some cities while also hampering economic recovery in the Rust Belt.

The increases could signal that some of the weaker housing markets, as in Cleveland, may see more homeowners go underwater, owing more on their mortgage than their homes are worth, triggering a cascade of foreclosures similar to the one from 10 years ago, said James Gaines, chief economist at Texas A&M University’s Real Estate Center.

But for some of the high-flying real estate markets in cities like Denver and Austin, the rare increases may be early warning signs of trouble to come if credit gets too loose, said Daren Blomquist, a vice president at ATTOM Data Solutions, which tracks foreclosure starts.

To be sure, in some cases, an increase in foreclosures could paradoxically be a good thing if the shift signals streamlined procedures that help get abandoned homes back on the market, or if banks are finally starting to foreclose distressed properties because higher property values make it worthwhile.

Austin and Columbus posted their largest increases in foreclosure starts since 2012, the bottom of the housing bust, while Nashville and Dallas had seen foreclosure starts drop for about two years before the recent increase.

In some of the stronger markets, banks may see more incentive to foreclose quickly because the homes likely could be sold at a profit, Gaines said.

There’s a tendency for banks to lend too much when prices are rising and resale value is harder to predict, but “in a rising market, they’re going to be OK anyway,” Gaines said.

The upturns could spell trouble, though, for bustling housing markets in middle America, which have been fueled recently by buyers’ sticker shock in coastal areas, a strengthening economy and looser credit, starting in 2014, with down payments as low as 3 percent.

The highest rates of foreclosure in Austin, Dallas, Denver, Nashville and Columbus are for mortgages that started in 2014, Blomquist said. That looser credit, meant to entice first-time buyers to the market, has added instability to the housing market because homeowners have less incentive to weather hard times and keep paying the mortgage, he said.

“With lower down payments, the borrower has less skin in the game, and that’s just inherently more risky,” he said. “It can take a few years for the chickens to come home to roost, and I think that’s what’s starting to happen.”

Foreclosures in the Rust Belt

But foreclosures are up in some struggling regions too. In Ohio, where three metro areas saw upticks, foreclosure has been a fact of life despite rising housing prices since 2000, said Donald Haurin, a real estate economist at Ohio State University.

“It’s a typical Rust Belt story, so one hypothesis is that we’ve returned to that story,” Haurin said. As in the booming housing markets, loosening of credit and lower down payments also contribute to the foreclosure rate, he said.

Ohio has one of the highest unemployment rates in the country at 5.1 percent, behind only Alaska and New Mexico.

In one sense, foreclosures may be a good thing for Ohio’s state economy, said state Rep. Jonathan Dever, a Republican from Madeira, near Cincinnati.

Cleveland and Cincinnati have been plagued by so-called “zombie homes,” abandoned properties that banks have not foreclosed because the cost of doing so could be more than the homes are worth.

A 2016 Ohio law streamlined the foreclosure process for abandoned houses so they can be sold and put back on the market, said Dever, who sponsored the bill. At the same time, there are options to help homeowners stay in a home while they try to work out financial problems.

For instance, if the bank agrees, a homeowner in foreclosure can give up title to the home and pay rent for up to two years, Dever said.

“These houses were just sitting there contributing to blight and crime, and now the banks can sell them, people get more housing, and neighborhoods don’t have the problems,” Dever said. “Everybody’s happy.”

Wisconsin, where Milwaukee foreclosure starts nearly doubled to 507, also enacted a law last year cutting foreclosure times for abandoned homes.

Andrew Reschovsky, a fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and a former economics professor at the University of Wisconsin, said actual foreclosures — rather than the foreclosure starts tracked by ATTOM — are still down in Milwaukee, and it’s too soon to say whether the recent increase is a sign of trouble to come.

Nationwide, a Low Ebb

Despite the increases in some cities, foreclosures are at a low ebb nationally.

Banks started the foreclosure process on only 93,724 properties in the third quarter, down 16 percent from the previous year to the lowest level since 2005, when ATTOM Data Solutions began tracking them.

Anything banks can do, as in Ohio, to keep homeowners in their homes during foreclosure is “a great idea,” said David Berenbaum, CEO of the Homeownership Preservation Foundation, a nonprofit that operates a telephone hotline for homeowners who face foreclosure.

The foundation handles between 800 and 1,100 calls a day, he said. That’s down slightly from 2016, but people are calling later in the process, when their financial troubles are harder to reverse.

“For some reason they’re waiting longer to ask for help,” Berenbaum said, “and they’re already further behind.”

Job security has improved somewhat as unemployment declines, he said, but he hears from many middle-class people who are underemployed in part-time or low-paying jobs and can no longer keep up with payments.

“A stronger economy doesn’t necessarily translate into stronger income for homeowners,” Berenbaum said.

A growing reason for falling behind: Baby boomers reaching retirement age while still carrying their children’s student debt, Berenbaum said.

And the number of foreclosure starts could grow soon in places like Houston and South Florida, Gaines said, because so many people were not able to get to work in the aftermath of this year’s storms.

NEXT STORY: Collins Files SALT Amendment, as Senate Votes to Debate Tax Bill