Why Cutting Historic Preservation Tax Credits Won't Be Easy

Mineral Point, Wisconsin Shutterstock

Connecting state and local government leaders

Preservation advocates, small town mayors, commercial developers and builders argue the credits more than cover their costs by generating jobs and tax revenue.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts and was written by Elaine S. Povich.

Warning to congressional Republicans who want to kill the federal Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit, a Reagan-era program to revitalize historic buildings, as a way to save $1 billion annually: It doesn’t die easily.

Efforts to roll back similar tax credits in a handful of states have run into opposition from preservation advocates, small town mayors, commercial developers and builders, all of whom depend on the credits to fund the reconstruction and revitalization of historic downtowns and rural buildings—and argue the credits more than cover their costs by generating jobs and tax revenue.

In Wisconsin, Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican, pushed for years to kill the state credit, but faced opposition from developers and preservationists. This year, he managed to trim the credit back, capping it at $500,000 per project. The result: Developers are trying to get a flood of construction projects in under the wire before the cap takes effect in July—and state legislators have vowed to raise the cap next year.

In Nebraska, a slew of bills were introduced in 2017 that would have ended the credit in 2018 or capped it, according to Trevor Jones, director of the Nebraska State Historical Society. They were then folded into an omnibus tax reform bill that failed to pass. Lobbying by business and preservation groups killed the stand-alone bills, he said, adding that the same forces are prepared to fight the proposal next year.

Jones pointed to a University of Nebraska-Lincoln study that found that in 2015, the first year of the credit, projects undertaken had a $120.7 million impact on the Nebraska economy, created 1,635 full-time jobs, and contributed $5.1 million in state and local taxes. The state spends $15 million a year on the program.

And in Missouri, Gov. Eric Greitens, a Republican, campaigned last year on getting rid of “special interest tax credits,” including the state’s historic preservation tax credit, which cost the state $1.1 billion over a decade.

Supporters of the historic preservation tax credit are gearing up for what they expect to be a struggle to protect it. Jim Farrell, a lobbyist and political strategist in St. Louis who works with preservation advocates, said the program has helped more than 80 communities around the state, both urban and rural, and spurred almost $9 billion of private investment.

Farrell has traveled across Missouri to draw attention to projects that have saved buildings and spurred adjacent development. “Without a doubt, the majority of these projects would never have happened without the credit,” he said.

Other states have moved to expand or redistribute their historic preservation tax credit. West Virginia this year boosted the credit from a maximum of 10 percent of the cost of a project to 25 percent, on a par with surrounding states. Alabama renewed its credit this year, and rewrote the formula so that rural counties could be eligible for 40 percent of the credits, the lion’s share of which had previously gone to larger communities like Birmingham and Mobile.

According to John Leith-Tetrault, chairman of the Historic Tax Credit Coalition, a D.C.-based lobbying organization of preservationists and financial, real estate and development companies, without the credit many of the restoration projects that have helped revitalize downtowns across the country would never have happened.

Restoration projects typically cost more than new construction because many of the projects face environmental issues and must meet costly preservation standards, Leith-Tetrault said. “The purpose of the credit is to close the financing gap between what a bank will lend on a project and what it actually costs.”

But in a time of tight budgets, proponents say, that may not be enough to protect the credits.

According to Michael Novogradac — a managing partner of the accounting firm Novogradac & Company LLP and board member of the Historic Tax Credit Coalition lobbying group who hosts the weekly podcast “Tax Credit Tuesday” — House and Senate tax writers, trying to find ways to pay for tax cuts, may “go looking for all these little credits.”

Sprucing Up the Elks Club

The federal version of the tax credit was made permanent under the Reagan administration and has been used in every state and nearly every county over the past few years.

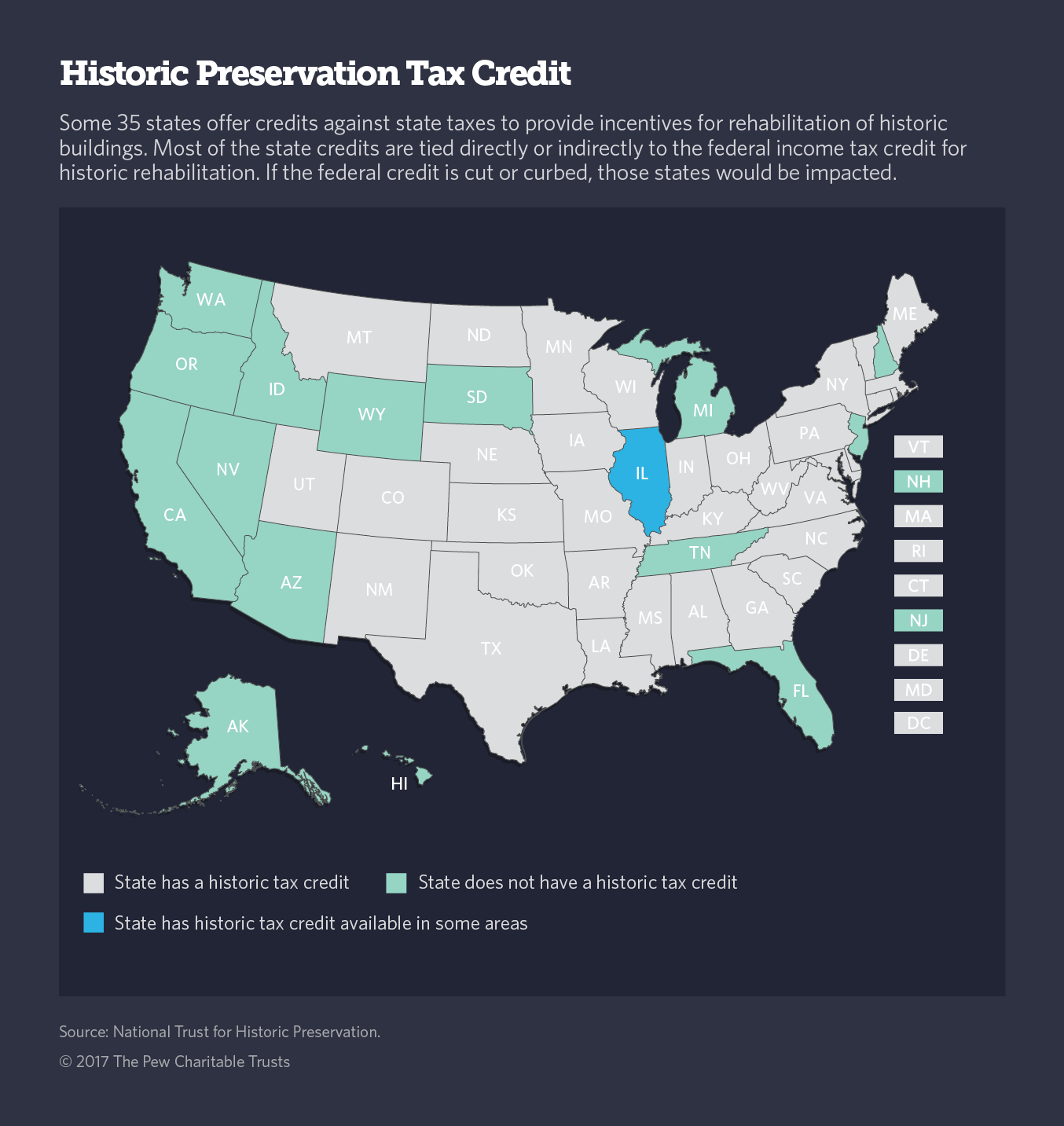

Thirty-five states have their own credits, most modeled after the federal one. In half a dozen states, a project must get federal preservation credits before it qualifies for state credits. But even if they are not directly tied to the federal program, expensive projects often combine federal and state credits to come up with enough money.

According to a study by Rutgers University and the National Park Service, which helps administer the program, the federal credit created 108,528 new jobs in fiscal 2016 and is responsible for $120.8 billion in investment in urban and rural communities over the life of the program.

Advocates argue that the federal credit returns $1.20 for every dollar spent in the form of property taxes, income taxes on construction workers and taxes from ancillary businesses that spring up around the rehabbed property.

They make a similar argument about the state credits. In Wisconsin — where the credits have been used for the conversion of the historic Kenosha Elks Club into a boutique hotel — a study by the Historic Preservation Institute at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and the accounting firm Baker Tilly showed the state receives 110 percent over its initial investment in the first 10 years of the project, including higher property tax payments on redeveloped properties.

But critics say they are a giveaway to developers and that the buildings deemed “historic” are just plain old, and not worth preserving. Critics also argue that the money spent for the credit could be better used for other things.

For example, a 2014 report by the Missouri state auditor called the state’s program an inefficient use of resources: “Only 49 cents to 85 cents of every tax credit dollar issued actually goes toward rehabilitation costs.”

According to an analysis of the Republican tax bill approved in the House this month, eliminating the federal credit would save $1 billion annually by 2021. That’s the bottom line for budget writers: It saves money, to make up for tax cuts elsewhere in the GOP tax plan.

In the Senate, the initial Republican bill would have cut the federal credit in half. But after U.S. Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana heard from constituents who support the credit, including Preserve Louisiana, a coalition of developers and preservationists, he successfully pushed to reinstate the original 20 percent credit.

The Louisiana group was one of several that mobilized to protect the federal credits. The American Institute of Architects, among many financial, legal, investment and real estate groups, as well as Sherwin-Williams, the paint company, immediately organized a lobbying campaign in an attempt to save the credit.

Eric Hein, executive director of the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers, says as in Washington, those who want to curb the state credits also look at it as a cost-saving mechanism, because the state doesn’t have to lay out the money for the credit. But, Hein said, “They don’t look at economic activity generated by the credit and buildings brought back on line that were generating nothing.”

Renee Kuhlman, director of policy outreach at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, said advocates for preservation are fighting on two fronts: in the states and in Washington. And she suggested that state lawmakers are often persuaded by successful redevelopment projects in their towns.

“Because the program works in small towns and big cities, I think legislatures understand that,” she said. “Despite some effort to limit these programs, they haven’t been successful. These programs are job creators, and that’s what state legislators are really looking for.”

NEXT STORY: As States Face Sluggish Revenue Growth, They’re Threatened by Federal Policies