Why It’s Getting Easier for Marijuana Companies to Open Bank Accounts

A medical marijuana dispensary in Springfield, Or.

Connecting state and local government leaders

Banks and credit unions are becoming more comfortable serving marijuana businesses. But the progress could be wiped out by President Trump’s Justice Department.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Sophie Quinton.

State and local officials in places that recently legalized marijuana are bracing for the arrival of a sector that largely runs on cash. They’re anxiously envisioning burglars targeting dispensaries and business owners showing up at tax offices with duffel bags full of money.

But the marijuana industry’s banking problems may be more manageable than many officials realize.

Just ask Washington state, which last year successfully pushed almost all legal marijuana businesses to open bank accounts and pay their taxes with a check or other non-cash method. Or Hawaii, which earlier this year announced a “cashless” system for buying medical marijuana, reliant on a technology analogous to PayPal.

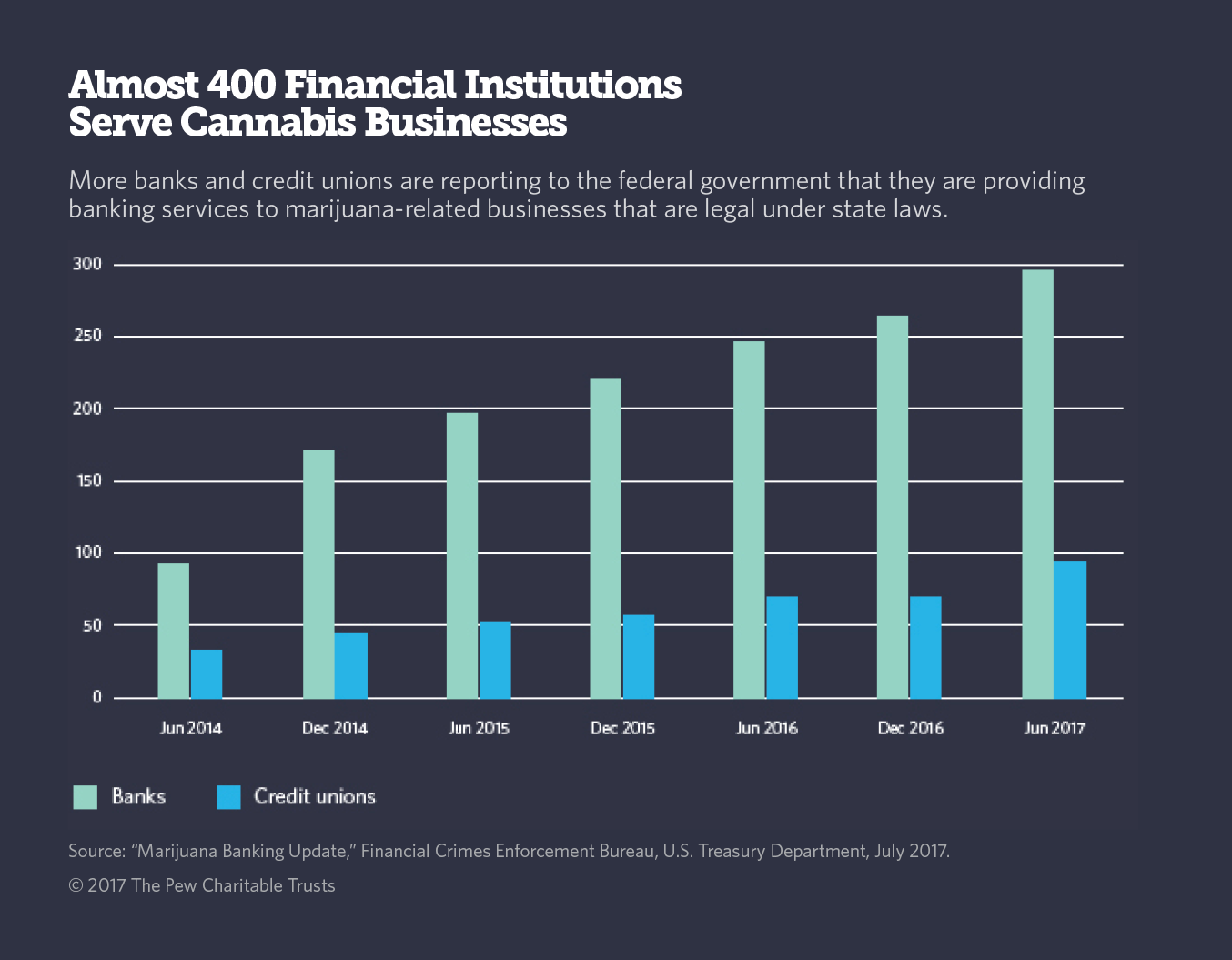

“We’re definitely seeing more businesses in the industry getting banked every day,” said Aaron Smith, executive director of the National Cannabis Industry Association, a trade group. Despite the legal risk involved in serving the cannabis industry, almost 400 banks and credit unions now do, according to the U.S. Treasury — a number that has more than tripled since 2014.

That’s reassuring news for California, where sales of recreational pot start next month, as well as for Nevada, Maine and Massachusetts, where voters approved recreational marijuana sales last year, and Arkansas, Florida, Montana and North Dakota, where voters approved medicinal sales.

But the progress that has occurred in some legal markets remains fragile. The federal government still considers marijuana to be a dangerous, illegal drug. States can only permit marijuana sales — and financial institutions can only serve marijuana-related businesses — thanks to Obama-era guidelines that create wiggle room in federal law.

The Trump administration is rethinking those guidelines. “We’re looking at that very hard right now, we had a meeting yesterday and talked about it at some length,” Attorney General Jeff Sessions said at a press conference last week. “It’s my view that the use of marijuana is detrimental, and we should not give encouragement in any way to it, and it represents a federal violation, which is in the law and is subject to being enforced.”

Growing Access to Banking Services

Since the U.S. Treasury issued guidance on the issue in 2014, banks and credit unions have been able to do business with the marijuana industry without being prosecuted — so long as they monitor marijuana-related accounts closely to make sure they steer clear of Justice Department enforcement priorities, such as funding gang activity.

Local institutions that are chartered at the state level have been particularly willing to work with the industry.

In Oregon, where sales of recreational marijuana began in 2015, Salem-based Maps Credit Union decided to serve marijuana businesses after audits revealed some of its members were already in the industry. “It didn’t really square with our philosophy to kick members out,” said Shane Saunders, chief experience officer.

Taking on the new line of business required investments in staff, anti-money laundering software, and extra security at bank branches, said Rachel Pross, the credit union’s chief risk officer. Under the current federal guidance, Maps has to send a report on each marijuana-related account to the U.S. Treasury every 90 days, plus a report each time an account experiences a cash transaction of over $10,000.

Maps staff run background checks on marijuana-related business owners who want to open an account. They conduct regular, in-person inspections of the businesses whose accounts they manage, and they require business owners to share their quarterly financial statements.

Dispensaries that bank with Maps make most of their sales in cash, because credit- and debit-card processors typically won’t touch marijuana money. As of October, the credit union had handled $140 million in cash deposits from 375 marijuana-related accounts in 2017, Pross said. Some companies hold multiple accounts.

In neighboring Washington, where recreational marijuana sales began in 2014, several financial institutions are openly working with the industry.

Washington has helped banks and credit unions monitor marijuana-related customers by collecting and publishing extensive data on monthly sales and legal violations to the liquor and cannabis control board’s website.

State regulators last year nudged marijuana licensees to open desposit accounts, aware that banking services were available and worried that cash-based businesses threatened public safety.

“We gave them a deadline at some point in 2016,” said Brian Smith, communications director for the liquor and cannabis board: Either prove you can’t get a bank account, or the state won’t accept tax payments in cash.

Some marijuana businesses weren’t using banks not because services weren’t available, Smith said, but because they weren’t keeping careful track of their finances and obeying the law. Today, most businesses have accounts and about 99 percent of taxes are paid in a form other than cash, he said.

Some cash-reliant businesses complained about bank fees, which are typically higher for marijuana-related accounts than accounts that require less monitoring. Regulators were unsympathetic. “It’s a cost of doing business in this marketplace,” Smith said.

John Branch, a Seattle-based lawyer who owns a dispensary, says that fees are typically reasonable for small businesses like his. The fees he pays as a credit union member are in the hundreds of dollars, he said. “In the scheme of what it costs to run a marijuana business, it’s de minimis.”

A National ‘Cashless’ Model?

In some states, such as Alaska and Hawaii, regulators say they’re not aware of any credit unions or banks that currently serve the industry. Recreational marijuana sales began in Alaska in 2015, and medical marijuana dispensaries opened in Hawaii in 2015.

But Hawaii is pioneering a workaround.

Regulators have given a Colorado-based credit union permission to serve the state’s medical marijuana dispensaries. The credit union, in turn, has partnered with CanPay, an app that allows patients to transfer money from their bank accounts directly to the dispensary’s account.

“This new cashless system enables the state to focus on patient, public and product safety while we allow commerce to take place. This solution makes sense,” Hawaii Gov. David Ige, a Democrat, said in a statement announcing the system in September.

Hawaii doesn’t require dispensaries to use CanPay or become members of the credit union, according to the state Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs. Currently, three of the state’s four open dispensaries use the app, said Iris Ikeda, Hawaii’s state commissioner of financial institutions.

“We are calling this a temporary solution,” Ikeda said. Policymakers hope that eventually a state-chartered bank or credit union will step in to serve the marijuana industry, she said.

State and local officials in other parts of the country are watching Washington and Hawaii closely and asking if their strategies might work elsewhere.

The California Treasurer’s office, facing the January 1 launch of what’s projected to be a $7 billion legal cannabis industry, has pointed to Washington’s data-sharing system as a possible model to emulate. But the Golden State can’t copy Washington’s centralized system exactly, because localities and several state agencies will share responsibility for supervising California’s marijuana businesses.

The California State Association of Counties is working on building a website that would publish locally collected information on licensees. Cara Martinson, the federal affairs manager for the nonprofit association, says the database would help cities and counties audit licensed businesses and keep track of their transactions, as well as giving more information to banks and credit unions.

Ikeda says that it may be easier to introduce electronic payment processing to new marijuana markets than long-established ones, and easier to get medical marijuana patients to sign up to use the app than recreational users, who might be leery of giving their names and financial information to a third-party payment processor.

Seattle dispensary owner Branch notes that stores with ATMs make money when they dispense cash, and store owners may not embrace an electronic payment system that instead will cost them 2 percent of each transaction, as CanPay’s service does.

A change in federal law would solve the cannabis industry’s banking problem and wipe away the need for services tailored to the industry, such as CanPay. But Congress has so far failed to pass — or even seriously consider — a law that would reclassify marijuana as a less dangerous substance or allow banks and credit unions to work with businesses without risking their charters.

U.S. Rep. Ed Perlmutter, a Colorado Democrat who proposed a bill on the issue this year, says no action is expected anytime soon.

NEXT STORY: 2 Key Ways Federal Tax Reform Would Affect States