Not Out of the Woods Yet—State Borrows $100 Million As it Looks to Solve Forest Controversy

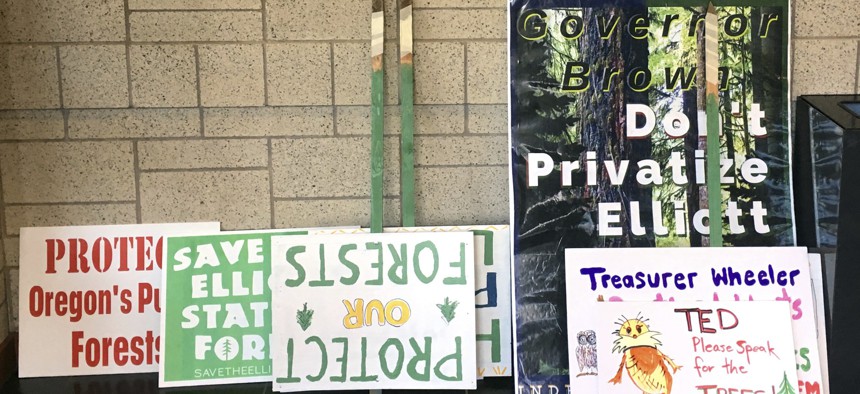

Protest signs are left outside a meeting room as more than 200 people gather at the Keizer Community Center for an Oregon State Land Board meeting Tuesday, Dec. 13, 2016, in Keizer, Ore. AP Photo/Andrew Selsky

Connecting state and local government leaders

The story of Oregon's Elliott State Forest is one of logging, litigation, old trees, imperiled animals, and school funding.

Oregon last week finalized a deal to borrow $100 million that should help the state buy more time to determine what to do next with a public forest that for years has been at the center of controversies and court battles pitting logging interests against conservation groups.

Elliott State Forest is roughly 91,000 acres and is located about 13 miles inland from the Pacific Coast, near the city of Coos Bay. Most of it is part of a 750,000-acre inventory of public land that generates revenue for what’s known as the state’s Common School Fund—a pool of money that typically funnels millions of dollars to public schools each year.

Measured against other public lands in the west, “the Elliott” is not huge. While its footprint is a little more than twice the size of Washington, D.C., it is dwarfed, for example, by the nearby Siuslaw National Forest to its north, which is about 630,000 acres.

But the modestly sized forest has stirred passionate debate and legal wrangling.

This stems largely from the fact that it is valuable for both its loggable timber and for the habitat it provides for imperiled species such as a seabird called the marbled murrelet, the spotted owl and Coho salmon.

Keeping it open for uses like camping, hunting and fishing is also a concern.

About half the forest has been logged since the 1950s. But the other half of its acreage contains older trees. It’s these areas conservation groups are mainly concerned about protecting.

"It stands out like a sore thumb in the Oregon coast range which is otherwise heavily fragmented and logged over through 100 years of industrial forestry,” says Josh Laughlin, executive director of Cascadia Wildlands, a conservation group based in Eugene, Oregon.

Timber sale revenue from the Elliott State Forest ranged from $3.6 million to $16.6 million annually between 1997 and 2012. But since then, because of logging limitations prompted by a lawsuit, the forest has been losing money, according to the Department of State Lands.

The state plans to direct the $100 million it borrowed to the Common School Fund as it explores how the Elliott might be “decoupled” from its obligations to produce education revenue.

Meanwhile, discussions are underway about the possibility of Oregon State University managing the land as a “research forest.” What that could mean for the forest’s future is still unclear, but a plan for how the arrangement could look is due in December.

"A forest of that scale is not commonly dedicated towards research,” says Anthony Davis, interim dean for the College of Forestry at OSU.

Davis cites big looming questions about climate change, wildlife conservation and the future of rural economies as he discusses the possible project. “If we set up a forest like this properly,” he said, “maybe we would be in a better position to answer those questions when they come at us.”

Both timber and conservation groups say whether they back plans for the research forest will depend heavily on the details of how it would operate, and what logging it would involve.

Fraught History

There are still raw feelings among some in the Pacific Northwest timber industry over actions by the federal government in the 1990s to protect northern spotted owl habitat—moves that sharply reduced the logging of old growth forests.

“We lost tens of thousands of jobs, we lost literally hundreds of mills throughout the 1990s and the early 2000s,” says Jim Geisinger, executive vice president of the trade group Associated Oregon Loggers. In more recent years, he said, “things have kind of stabilized.”

“In the political environment that we are involved in relative to public lands, there doesn't seem to ever be any end in controversy. There's no truce,” Geisinger added. “There's no amount of things that we can do that seems to satisfy the environmental community.”

But Jason Gonzales, an organizer with the group Oregon Wild, who has worked on advocacy efforts related to the Elliott for about a decade, says only a fraction of Oregon’s land hasn’t been logged, and that these areas should be left that way.

"The industry loves to call us extremists,” he said. “But I think the position that eight percent of Oregon's forests should be protected and never logged, there's nothing extreme about that. And the idea that all of it needs to be logged and managed I think that is very extreme.”

"They want to get every last big tree that they can because they make more money,” he added.

The eight percent figure, Gonzales said later by email, is an estimate of the land in the state that has never been logged and reflects mapping that conservation groups have done with limited historical data.

Geisinger says about half of Oregon's forest are protected from logging.

But Gonzales counters that the share of land in the state protected permanently by "durable law" is more like four percent, while a wider range of areas are off limits due to administrative policies or restrictions tied to the Endangered Species Act.

While there are parts of the Elliott that have not been logged, much of the forest did burn in a massive forest fire in 1868.

This means that most of the mature trees there—predominantly Douglas firs—are 100 to 130 years old, by no means among the oldest among forests in the Pacific Northwest. But advocates argue that these trees provide important wildlife habitat.

Cascadia Wildlands, along with the Audubon Society of Portland and The Center for Biological Diversity sued Oregon’s Department of State Lands over a 788-acre timber sale in the Elliott in 2014. The timber company seeking the tract intervened in the case, opposing the groups.

The conservation groups alleged the sale was illegal under a state law that prohibits selling certain land in the forest that was previously part of national forests—this particular track fit that bill. A state appeals court sided with the groups, blocking the sale.

Documents for the borrowing deal completed last week note the legal dispute over the sale is now pending before Oregon’s Supreme Court.

In 2012 the same groups that brought that case sued the state for illegally logging marbled murrelet habitat in the Elliott and other lands. The state settled in 2014, agreeing to drop 26 timber sales and to stop logging the seabird's habitat, according to Portland Audubon.

The groups also sued companies in federal court in 2016 to block logging in an area that had been part of the state forest, arguing the land is home to murrelets. That case is ongoing.

Geisinger says shutting down logging in the Elliott is a big deal, even though it is just a small fraction of the roughly 30 million acres of timberland in the state. “There are mills,” he said, “that depend and have depended on timber from the Elliott State Forest for decades.”

“It's just one more nail of many in our coffin,” he added. “That forest has always been intended to be a working forest to produce economic, environmental and social benefits.”

‘Dark Ages Policy’?

Oregon’s governor, treasurer and secretary of state make up Oregon’s State Land Board, which oversees the Elliott and other lands that generate money for the Common School Fund.

In 2017, facing opposition from conservationists, the board scrapped plans to sell the forest after getting a lone bid from a timber company partnered with a local Native American tribe.

Gov. Kate Brown, a Democrat, that same year released a proposal for keeping the land public, which called for issuing up to $100 million in bonds to help protect sensitive areas.

State lawmakers followed up with an authorization that paved the way for last week’s sale of $100 million in “certificates of participation,” which are similar to bonds. Interest costs for the certificates will total about $45 million over the coming two decades.

The Common School Fund has roots in Oregon’s admission to the U.S. in 1859, when the federal government granted the state about 3.4 million acres “for the use of schools.”

These days the fund makes the bulk of its money in returns from investments like stocks and private equity. It ended fiscal 2018 with total fund balances of about $1.3 billion, reporting $149 million in revenues, with about $128 million coming from investment income.

Distributions from the fund to the state’s Department of Education are based on a formula that factors in the fund’s revenues, with payments during fiscal 2020 slated to total $56 million.

One issue with the $100 million the state borrowed is that it is far short of the $221 million appraised value of the forest. It’s not certain where the other $121 million might come from to make up the difference if the forest is to be effectively bought out from the fund.

"We don't have $121 million dollars,” OSU’s Davis notes.

But Laughlin explains that even the $100 million should take pressure off the State Land Board in the near-term to make money from the Elliott. Although it’s still uncertain at this point what parts of the forest the money might ultimately go toward preserving.

Laughlin says his group and others believe the money, “should be going to permanently protect the outstanding acreage on the Elliott.” But he also acknowledges that “we haven't gotten any guarantees from any leadership in Salem that that's actually the case.”

"We need to sever the tie between the Elliott State Forest and the school fund,” he added. “It's dark ages policy to try and link clear cutting old growth forest with school children's educations."

‘Great Responsibility’

Both Gonzales and Laughlin emphasized that they’re not opposed to logging in parts of the Elliott where the forest was razed previously—areas that tend to include Douglas firs that are all about the same age and that Laughlin describes as resembling a corn crop.

But “the buck stops,” Laughlin said, when forest owners or agencies start meddling in mature, older forests that provide habitat for “species that continue to teeter on the brink of extinction.”

Gonzales, meanwhile, is critical of OSU’s stewardship of other forests it oversees and worries that the university could take a similar approach with the Elliott. He’d prefer to see the forest transferred to the Siuslaw National Forest, or managed by Oregon’s parks department.

But he realizes the political will for those alternatives for now appears limited, and says Oregon Wild remains open to the OSU partnership if it has safeguards the group views as adequate.

Geisinger, with Associated Oregon Loggers, suggests his group could support the research forest if it involves a plan that produces enough timber and enough revenue to pay for the forest’s management costs, and to make payments to make the Common School Fund whole.

“That might be something that we could get behind,” he said.

OSU’s Davis says discussions about what kind of research and activities to conduct in the potential research forest need to include a broad group of stakeholders and are now only in their initial stages. “There's a great responsibility to ask transformative questions,” he said.

"Saying which trees would be okay to cut and which trees wouldn't be okay to cut,” he added, “it is too early to say anything about that."

Editor's note: This story was updated after publication to provide additional information about an estimate of how much land has been logged historically in Oregon.

Bill Lucia is a Senior Reporter for Route Fifty and is based in Olympia, Washington.

NEXT STORY: State Bill Seeks to Clamp Down on Pension Benefits for Lawbreakers