Pandemic Aid: What Can We Learn From the 2009 Stimulus?

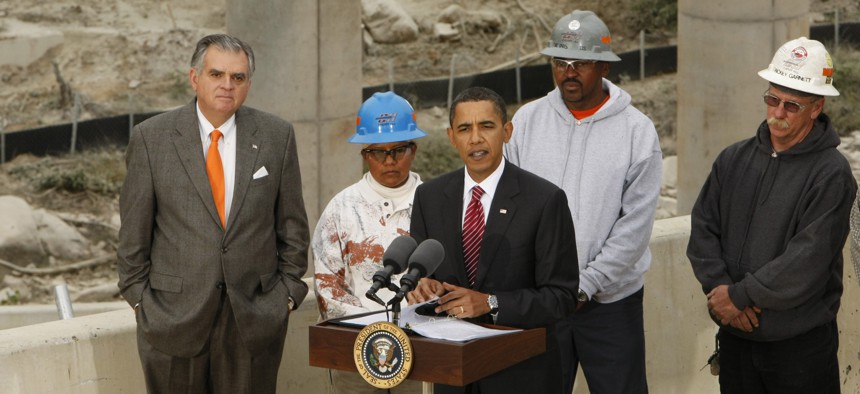

Former President Barack Obama makes remarks about the Recovery Act during a tour of the the Fairfax County Parkway extension project in Springfield, Va. on Oct. 14, 2009. Former Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood is at left. AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

Connecting state and local government leaders

COMMENTARY | As state and local leaders wait to see if they will get more federal aid to deal with their growing revenue shortfalls, fiscal stability will be more attainable by paying heed to experts who helped the country out of the Great Recession.

So far, state and local government leaders say they have gotten only a fraction of the federal aid they need to properly help their communities rebuild from the economic devastation of the coronavirus pandemic. Most argue they will need billions more just to plug budget holes or will be forced to make painful cuts to services.

In March, Congress passed the $2.2 trillion CARES Act, which includes about $200 billion in aid for states, localities, schools and higher education institutions. But that aid cuts out many communities and doesn’t provide governments help in dealing with revenue losses. While a new, more flexible $3 trillion relief package was passed by the House in May, it faces opposition in the Senate and momentum has stalled in recent weeks.

Experts caution that without more help, the actions state and local governments will need to take could actually make the broader recession worse.

“State and local governments cutbacks will deepen the economic downturn unless they get assistance from the federal government,” says Tim Conlan, professor emeritus at the Schar School of Government and Policy at George Mason University and co-author of a book on the $800 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

One concern some Republicans have raised is that more aid will just be a “bail out” for irresponsible states, particularly those run by Democrats. But the blow to revenues hits cities and states no matter what party is in power. When decisions are reached about future stimulus spending—probably in mid-to-late July—we are confident that a great deal can be learned from the 2009 Recovery Act, heralded, at the time, as the largest federal stimulus program ever. Much of that largess was funneled through states and locals. History may not teach us everything we need to know about the future, but it sure provides a useful guidebook.

So, we contacted an all-star team of sources who formed most of the backbone in the Recovery Act implementation: Ed DeSeve, who coordinated the Recovery Act stimulus program, working under then vice-president Joe Biden; Earl Devaney, the chair of the Recovery Accountability and Transparency (RAT) Board, the key stimulus oversight body; Danny Werfel, then controller at the Office of Management and Budget; Stan Czerwinski, then director for strategic issues at the Government Accountability Office (GAO), and Ray Scheppach, who was executive director of the National Governors Association at the time. We also talked with Conlan and John Kamensky, senior fellow at the IBM Center for the Business of Government—both keen observers of the Recovery Act and how it was implemented.

Our own take on the implementation of the 2009 stimulus, which we followed closely, was that in the main it worked well, though with some notable flaws. For the most part, the money was spent quickly. It was very well coordinated; states and local governments were kept in the loop, and it was easy to see where the money was being spent and how quickly it was going out the door. Data from the RAT Board showed that accountability practices kept fraud to low levels—around 1%, according to Devaney, compared to the 5 to 7% that was originally projected for a large program of this kind.

One aspect of the Recovery Act that we particularly admired was the way its implementers managed intergovernmental relations. That’s lesson number one that the men and women involved in the pandemic response and recovery can learn from—and so far, need to—as attention to communication and partnership with state and local leaders has not been a strong emphasis of pandemic aid so far.

Communicating constantly with all the entities receiving and then, in turn, doling out stimulus dollars, helped the Obama administration's Office of Management and Budget know when the guidance they were writing worked and where it did not. Says Danny Werfel, OMB controller at the time, “It’s helpful to know if the guidance is manageable or if it is bureaucratically unnecessary. Getting the right people on a call gives you invaluable information.”

The 2009 Recovery Act also entailed close and constant federal communication with the National Governors Association (NGA), a variety of other state and local professional associations and elected leaders and staffers at the state and local level. “We created a network of mayors and governors and chief financial officers through the organizations they were associated with,” says DeSeve, the stimulus program coordinator. “Through intergovernmental networks, we could get things done quickly. That was absolutely essential.”

Another successful element of the 2009 Act that could be emulated now: Each state had a single responsible individual who looked after Recovery Act implementation and each had its own Recovery Act website. That added to a major focus on the transparency of spending on the federal Recovery.gov website, which allowed visitors to track stimulus spending by individual zip code.

Constant intergovernmental conference calls, missing in action currently, took place on many different levels in 2009. There were governor calls, budget director calls and “worker bee” calls.

“We had conference calls every week and sometimes every two to three days,” says Ray Scheppach, executive director of the NGA from 1983 to 2011.“We kept everybody on board.” Oversight officials from the GAO were often on the calls, too.

Another aspect worth emulating in any new stimulus package was real-time involvement of the GAO, which monitored implementation of the Recovery Act, with special attention to how it was playing out in 16 states and the District of Columbia. Alerted to problems, the GAO could immediately contact the governments that it was focused on and alert them to ways to avert those problems. It kept in constant touch with the Office of Management and Budget and with the inspectors general on the Recovery Board, as well as with state and local auditors. “That’s the first place we’d go to. They know this stuff,” says Stan Czerwinski, who was director of intergovernmental relations when he left the GAO in 2014.

“The accountability on the Recovery Act was real time,” he says. “Rather than waiting for the dust to settle and analyzing problems after the fact, the GAO was focused on spotting problems and helping to alleviate them.”

Of course, there are multiple differences between the situation during the Great Recession and now. The Recovery Act, which was passed in February 2009, came more than a year into the crisis, when the initial shocks had subsided. Federal action now is taking place in an election year, not in the first months of a new administration—and partisan politics have grown even more polarized. At the same time, levels of intergovernmental cooperation and trust are at a low ebb. The still uncertain impact of a pandemic—and the many unanswered questions about the immediate future—is also far different than officials faced in 2009.

Still, the fundamental elements for rapidly implementing a program of this kind remain the same. It takes coordination, teamwork, trust, and a willingness to openly confront problems to make a large stimulus program work. It takes the involvement of all the stakeholders in prioritizing effective implementation. “Is that going to happen here?” asks Werfel. “I hope so and I think there is a successful model to look to.”

Katherine Barrett and Richard Greene of Barrett and Greene, Inc. are columnists and senior advisers to Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: States Contemplate Borrowing to Help Manage Pandemic’s Fiscal Impact