Analysis: A new approach to defining persistent poverty

Residents gather food and supplies from a volunteer food pantry in the San Bernardino Mountain community in California on March 7, 2023. Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

COMMENTARY | Switching from using counties to census tracts in order to define persistent poverty may hurt rural communities and their chances when competing for federal dollars.

This story is republished from The Daily Yonder. Read the original article.

One of the federal government’s key indicators of economic distress—one that shows that rural counties are disproportionately suffering economically—is disguising persistent, intergenerational poverty that occurs in urban areas, a new study says.

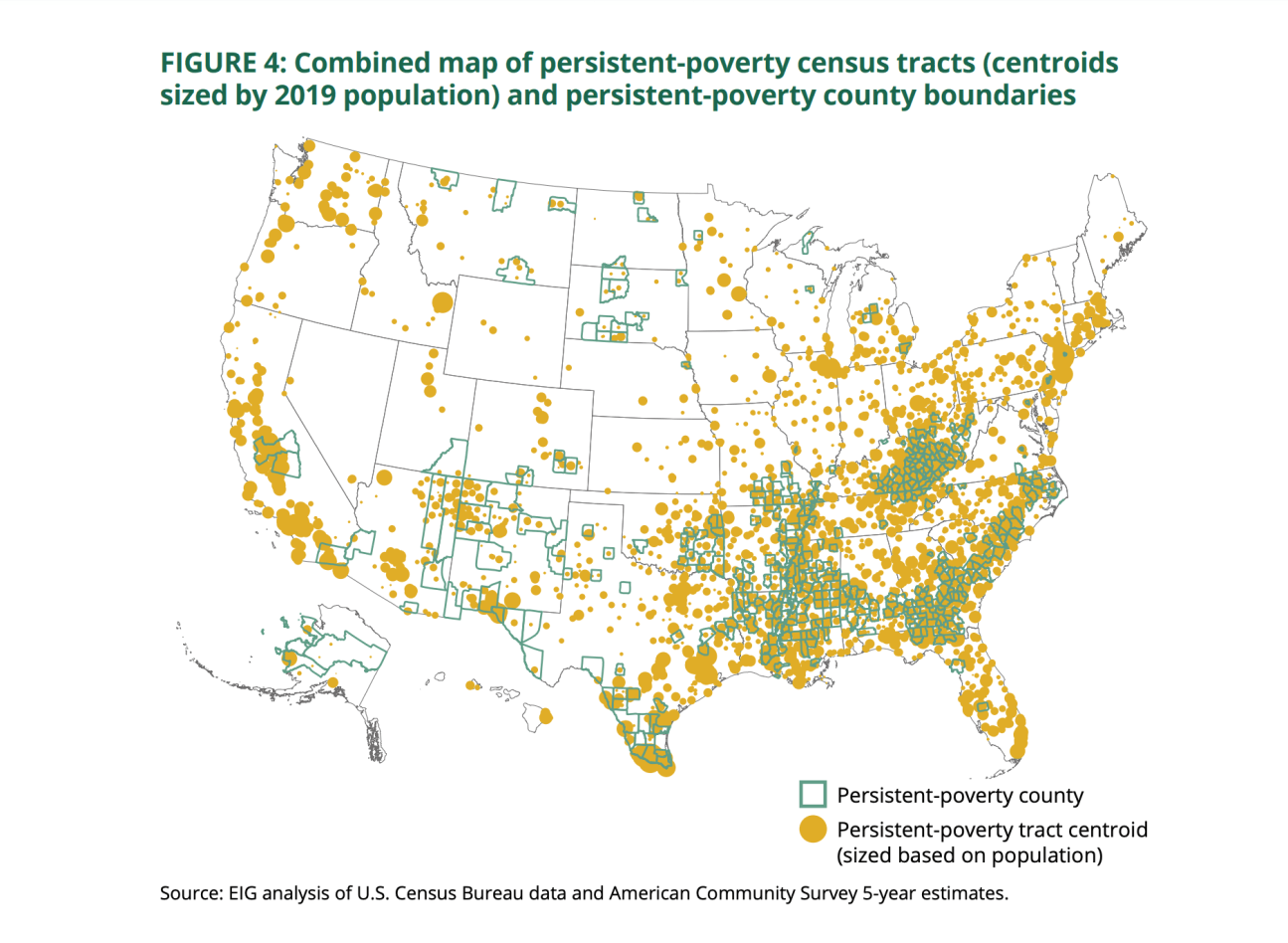

In a detailed new report, the Economic Innovation Group (EIG) says that using counties as the unit of evaluation for “persistent poverty” means that poor urban neighborhoods get overlooked when their economic performance is averaged with more prosperous parts of an urban county.

The result is a picture of persistent poverty that skews rural.

That problem could be addressed by looking at persistent poverty in census tracts, a smaller geographic measure, rather than in the traditional focus on counties.

Persistent poverty counties are ones where more than 20% of the population has lived below the federally defined poverty level for 30 years. The definition is important not just to those who study the economy; the definition also qualifies some localities for special federal support to help address long-term poverty.

Focusing on Census Tracts

Using census tracts instead of counties to evaluate persistent poverty changes the face of American economic distress. The U.S. has 415 persistently poor counties with 20.5 million people. The South is home to 81% of these counties, and 84% of the 415 counties are non-metro.

In contrast, EIG’s research shows that over 9,400 census tracts are persistently poor and have a population of 34.2 million people. All of the population increase in going from a county to a census tract methodology is in metropolitan areas. The study recommends defining persistent poverty areas as those with four contiguous persistently poor census tracts. These are termed “persistent poverty tract groups.”

The study points out that measuring “persistent poverty only at the county level misses large areas of persistent poverty” in urban areas. This is because metropolitan counties’ larger populations and greater economic diversity mean that they will not be persistently poor county-wide.

EIG also identified the 20 most populous persistent poverty tract groups. Thirteen of these 20 are in very large cities and 15 overall are urban.

The report focuses on the U.S. Commerce Department’s Economic Development Administration as a lead agency to carry out policies that could assist persistently poor areas. EDA funded the research.

The EIG report has several case studies. Two are rural: Gadsden County in Florida, and Big Horn County in Montana. Both are counties adjacent to growing cities, Tallahassee and Billings. Gadsden actually is metro, and Big Horn is metro adjacent. The experiences and challenges of these places may be quite different from more remote rural areas.

In both cases, the researchers say that urban proximity is more of an economic detriment than an advantage. Residents in the counties tend to go to the nearby cities to shop, work, and play.

Impact on Rural Communities

This new approach to persistent poverty that includes subsets of counties could help stimulate new interest from policymakers and elected officials in those areas. Certainly, high and prolonged levels of need in cities should be a focus of policy and programs. But would funding increase? As EIG points out, cities already have a significant advantage over small towns in capacity. For example, how many city staffers in New York or Detroit are devoted to applying for, carrying out, and administering federal grants and contracts? Compare that to very small towns with limited staff.

Changing from counties to census tracts to define persistent poverty may hurt rural communities. They often struggle to receive government assistance and lack the dedicated funds, which larger communities receive, which come with relatively large federal programs such as the entitlement portion of HUD’s Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program. Thirty percent of CDBG’s considerable funding ($3.47 billion in FY 2022) is set aside for non-urban communities through its non-entitlement (small states) program.

States award these funds to local governments on a competitive basis rather than in the guaranteed entitlements received by larger urban areas. This means that each state’s 32,851 non-entitlement units of local government must compete for funds. These smaller places often have the least capacity to produce a winning proposal.

For programs and policies where rural communities represent a relatively small part of communities eligible for assistance, the result is often that larger urban areas win most of the support. For example, the 2017 Opportunity Zone tax program encouraged investment in economically distressed areas, many of them rural. But in practice, the program has put almost all of its investments (95%) in urban areas. The same can be said of regulations like the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) which primarily incentivizes banking activity in lower-income urban/suburban areas. It is not that these programs are closed to rural communities, but that they are more easily accessed by larger urban areas.

A change to the definition may have unintended consequences. If consideration is not given to the larger geographies (rural counties) that have experienced chronic economic distress, the inclusion of smaller, urban/suburban areas alone might reduce efforts in rural areas. It is or may just be easier to invest in an area in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area than an isolated Central Appalachian county. Part of what makes persistent poverty counties chronically poor is their isolation and difficulty to serve.

Also, there are logistical concerns with this proposed definition. Census tract estimates and interpolations may have issues of accuracy.

Compromise?

It is true that the current definition on a county basis does overlook persistent poverty pockets in urban/suburban areas. These communities need investment and focused policies, something that should be promoted. This does not need to be a zero-sum game where one area/region is pitted against another. A hybrid approach that uses both county and contiguous census tracts to define persistent poverty could work. But efforts would have to be put in place to ensure such a change expanded investment rather than shifting where it occurred.

Overall, this very important and ground-breaking study deserves consideration. But would a focus on census tracts rather than counties lead to less attention to rural poverty? Rural advocates need a seat at the table.

![]()

Keith Wiley is a senior research associate at the Housing Assistance Council. Joe Belden is a writer and consultant based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: What happens when high-earners leave cities, taking their spending power with them?