An emerging ‘greenium’? New research says green bonds cost governments less

Rebuilding in the wake of the wildfires in Maui may be made less costly with a green bond, according to research. Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Amid an ESG backlash in some states, the finding could lead to more governments seeking an ESG-related label for bonds that will fund socially or environmentally sustainable projects.

You're reading Route Fifty's Public Finance Update. To get the latest on state and local budgets, taxes and other financial matters, you can subscribe here to get this update in your inbox twice each month. You can find a full archive of these newsletters here.

Welcome back to Route Fifty’s Public Finance Update. I’m Liz Farmer and this week, I’m looking at new research that suggests governments may be getting a discount on financing projects related to combating climate change.

The devastating wildfires in Maui, which has so far claimed the lives of at least 110 people, are just the latest in a series of storms made worse by global warming. On Sunday, Gov. Josh Green, appearing on CBS News' “Face The Nation," acknowledged there were critical errors by both local officials and private companies regarding the disaster that contributed to the rising death count. But he added that those mistakes were aggravated by climate change, which created conditions for the wildfire to spread rapidly and behave erratically.

“There’s no excuses ever to be made,” he said, “but there are finite resources sometimes in the moment.”

There’s no question Hawaii faces a long and expensive rebuilding process that will most likely include investing in its emergency warning systems and reservoir water diversion projects to better respond to future wildfires. But new research shows that projects like these may at least cost a little less to finance than they did before.

Governments have been issuing municipal bonds for resilience-related infrastructure projects for a long time. A little less than a decade ago, “green bonds” entered the municipal market as a way to help the world’s growing cadre of environmentally conscious investors identify climate-friendly investments. But despite this clear and growing demand on the investor side, it’s been unclear whether packaging a bond sale as “green”—which includes stating its environmental benefits and outcomes—is worth the extra hassle on the government’s end. At best, research has been mixed and reports of a so-called greenium, or lower cost of issuance, was anecdotal.

But a new paper titled “The Emerging Greenium” by researchers from the University of Florida and the University of China pinpoints 2019 as the year that the tide officially changed. The authors compared more than 1,000 pairs of green and non-green bonds issued between 2014 and 2022 that were otherwise identical on issuer, issuance date, maturity date, ratings, call dates and source of repayment.

Prior to 2019, green bonds cost slightly more than non-green bonds on average. After that, the data show that the costs associated with green bonds started to decrease and that investors were consistently willing to accept a slightly lower return, or yield, on green bonds when compared to non-green counterparts. In the most extreme cases, the total savings for governments amounts to a reduction of 24 basis points (or 0.24%) in the cost of issuance. On average, the cost savings for green bonds between 2019 and 2022 was 2.3 basis points.

The face value of these savings are small. After all, a 24-basis-point savings on a $1 million issuance amounts to $2,400. But the implications are bigger in that it could pave the way for better standardization of the green bond market via a clear financial incentive.

When are Green Bonds Worth the Extra Effort?

One of the biggest issues with green bonds in the municipal market has been a lack of standardization. The definition of what’s “green” seems to vary slightly with each issuer—even investors have different points of view on the matter. This lack of agreement has undermined the authenticity of the term “green bond” and, ultimately, any efforts to define their financial benefit to government issuers.

Since 2018, though, there has been a progressive increase in governments seeking external reviews for their green bonds. 2022 marked the first year in which externally verified green bonds outnumbered self-verified ones, according to Monica Reid, CEO of Kestrel, a firm that evaluates the sustainability attributes of bonds. (Firms like Kestrel verify a green issuance via a generally accepted industry standard such as the Climate Bonds Initiative’s climate bond certification or the International Capital Market Association’s green bond principles.)

“That creates efficiency,” Reid said at the Brookings Municipal Finance Conference last month. “If it has a second-party opinion, it can kind of get through the review process more easily and it saves [investors] a little bit of time—gives them a little bit of cover in a world of increasing regulation.”

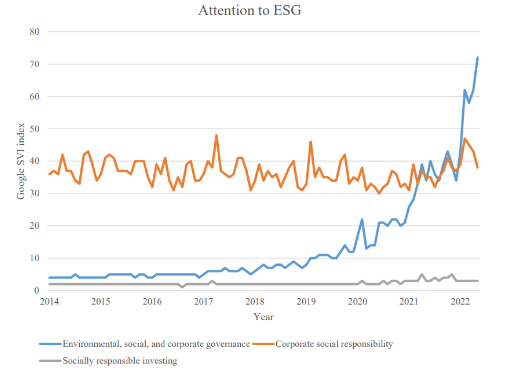

Baolian Wang, one of the paper’s authors, observed that the additional information and accountability also likely makes green bonds easier to market to investors, which could explain why his research shows underwriters are now charging issuers less for green bonds compared with similar issuances that are not “green.” He also pointed to a significant rise in Google search activity for the term environmental, social, and governance, or ESG, in recent years compared to other terms referring to socially responsible investing.

“It is clear that attention to ESG started to increase in 2019, coinciding with the emergence of a greenium,” Wang said.

The ESG Label Divide

Wang and Reid said they believe that the paper’s findings could support more governments seeking an ESG-related label for bonds that will fund socially or environmentally sustainable projects.

Kestrel recently analyzed nearly $1.5 trillion in outstanding issuance and found that 7% of the bonds in that total were eligible to be green, but not labeled so. Another 17% were unlabeled sustainability bonds. The cost for external verification, according to Reid, is less than 1 basis point and typically even less when multiple issuances are bundled. The emergence of a greenium, she argued, could make it financially worthwhile for governments to package their debt under an ESG label.

But in states like Florida, Texas and Utah that have enacted legislation seeking to curtail the use of ESG in public investments, that may be problematic. A recent article in the Economist noted that Florida and Texas have been paying out higher yields after banning municipal bond underwriters such as JPMorgan and Citibank for their pro-ESG stance. Texas local governments alone paid up to $500 million more in borrowing costs last year after anti-ESG legislation went into effect.

Ultimately, the emergence of a greenium for some may just be one more factor that increases the cost of climate change for others.