Why a government shutdown is complex for state and local governments

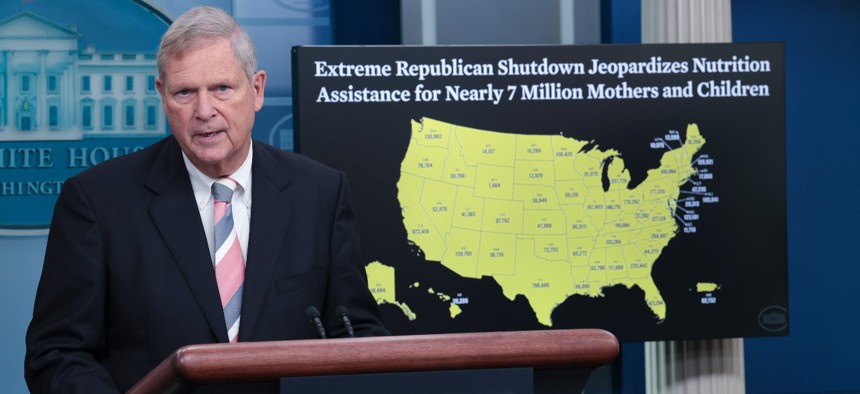

Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack answered questions during a daily briefing about how a potential government shutdown might affect welfare and food stamp programs. Win McNamee via Getty Images

It will impact welfare, food stamps, housing and infrastructure, among other things. But planning for a shutdown is difficult for a myriad of reasons.

With time dwindling for a still widely divided Congress to avoid a government shutdown, it’s appearing more and more likely that state and local governments will soon have to figure out what to do if funding for programs like welfare comes to a halt.

One big decision for states may be whether they will have to use their own money to fund the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. During the 2013 government shutdown, every state but Arizona opted to do so. The federal government will stop funding TANF should Congress be unable to pass a stopgap spending measure, according to an analysis by Federal Funds Information for States.

A primary challenge for states and localities is navigating the many different ways a shutdown will impact funding for programs.

Another big complication for states and localities in coming up with a plan for dealing with a shutdown is that it’s impossible to know how long it will last, said Brian Sigritz, director of state fiscal studies at the National Association of State Budget Officers, or NASBO.

The prospects of a shutdown continued to grow on Monday. While the Senate was working on a short-term spending measure to keep the government running, it remained uncertain if it would pass the House. It also continues to be unknown if House Republicans could agree on their own stopgap proposal to send to the Senate.

How States May Be Impacted by a Shutdown

While the federal government will stop funding TANF, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has not yet said if it will be able to provide benefits in October. If not, states will likely be able to use unspent funds or their own money to continue providing benefits, said Matthew Lyons, senior policy and practice manager for the American Public Human Services Association. However, he said, “the availability and extent of these resources will differ for each state. We are currently reaching out to states to take stock.”

In addition to TANF, states may also have to pick up the tab for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, or WIC, which helps feed low-income pregnant women and new mothers and their children. “The risk to vulnerable families is real,” said a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Department. “[The agency] likely does not have sufficient funding to support normal WIC operations beyond a few days into a shutdown.”

WIC is already facing a shortage of funding amid the rising cost of food and more women than expected signing up for a program. States could use their own funds or any leftover money to keep providing benefits, the spokesperson said. But how long they’ll be able to do that will vary by the state, and ultimately, some states may be forced to put those seeking help on waiting lists.

Funding for Medicaid will continue, but only through the end of the year, according to the U.S. Health and Human Services Department’s shutdown plans. Because housing choice vouchers are funded in advance, low-income people getting federal help paying their rent would still get it for the first few months of a shutdown, said Kim Johnson, public policy manager for the National Low Income Housing Coalition. But that money may run out at the end of the year if the government is still shut down.

Low-income families will receive their Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program food stamps in October, the Agriculture Department spokesperson said. The agency, though, declined to speculate on whether the benefits would continue in November.

There’s a chance SNAP benefits would end after 30 days, said Shana Christrup, public health director for the Bipartisan Policy Center. That’s what happened during the 35-day shutdown between December 2018 and January 2019, which was the longest in history.

States would also have to decide whether to furlough the employees whose positions are funded with federal dollars. During the 2013 shutdown, for instance, NASBO noted that several states did furlough employees. Other states issued layoff notices “to comply with contractual or statutory notice period requirements."

One potentially positive piece of news for states is that they may be in a much better position to keep programs going than in the 14 previous government shutdowns since 1980. That’s because they have been putting much more money in the bank. As a NASBO report noted last year, states have tripled how much they have stashed in their “rainy day funds” in the last two fiscal years.

Still, Sigritz noted that depending on how long the impasse continues, “the rainy day funds may not be enough to replace all of the federal funding” that would be shut off.

In a statement to Route Fifty, Hawaii Gov. Josh Green echoed Sigritz’s comments. “While we maintain an adequate surplus, it may not be sufficient to cover all the essential services during a prolonged shutdown,” he said. “We rely on federal reimbursement for a significant portion of our budget, especially disaster response and health care services.”

That’s why state budget offices around the country are preparing for the worst-case scenario—a shutdown. “They are aware of it, thinking about it and putting together a plan,” said Marcia Howard, executive director of Federal Funds Information for States, or FFIS, which was created by the National Governors Association and the National Conference of State Legislatures.

New Mexico officials are “actively considering potential workarounds if the federal government does not pass a budget,” said Henry Valdez, spokesperson for the state’s Department of Finance and Administration. “Currently, there are numerous variables beyond our control that we have to wait to unfold before we set any plan into motion.”

For instance, not only does New Mexico not know how long a shutdown may last, but it also doesn’t know for sure if it will be reimbursed. During past shutdowns, states were given back the money they spent to keep federal programs going. But there’s no guarantee that Congress will do that this time, according to the analysis by FFIS.

The Fallout of a Shutdown on Cities and Counties

Meanwhile, the potential shutdown has the attention of mayors as well.

In Clearfield City, Utah, Mayor Mark Shepherd worried that unless Congress reaches a deal on a short-term spending bill, thousands of members of the military and civilians at nearby Hill Air Force would stop getting a paycheck for the duration of a shutdown.

“Come October 1, they won't go to work and that flows down into my city,” he said. “They don't spend anything. They don’t want to buy anything and they have no idea when their paycheck may show up.”

So Shepherd was surprised when he met with members of Congress this week on behalf of the National League of Cities and was told by some that “this doesn’t affect cities. That if they shut down, it's not a big deal.”

With cities still recovering financially from the pandemic, Shepard said there’s likely not much they could do if, for example, funding for food stamps runs out. He also said that he is particularly concerned about the effects that he and other city leaders don’t see coming.

“If suddenly a program is cut off, you start hearing from residents,” he said. “If nobody’s picking up the phone at the federal level, they're going to turn to their local officials to figure out how to try to help them solve a problem.”

Another concern for local governments is that the federal offices they work with will close.

With cities scrambling to use American Rescue Plan Act funds before a Dec. 31, 2024, deadline, city officials have been relying on Treasury Department staff—who would be furloughed—to help them navigate the program’s complicated rules.

“We need those lines open,” said Michael Wallace, legislative director for housing, community and economic development at the National League of Cities. If a city can’t get a question answered, then grant administrators who are worried about not breaking any rules might have to put projects on hold, he said.

Mark Ritacco, chief government affairs officer for the National Association of Counties, said local governments work day to day with a number of federal agencies that might get shut down.

“There are offices and agencies throughout the federal government where we have a sort of collaborative relationship on the ground in Washington, D.C.,” he said, “everything from public land management agencies to the forest service to the Department of the Treasury.”

Affecting both states and localities, according to the White House, is that a shutdown would delay infrastructure projects around the county. Federal workers at agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of the Interior would be furloughed, delaying environmental reviews.

The Complexity of Planning for So Many Unknowns

On Friday, the Office of Management and Budget directed federal agencies to release their plans on how programs would be impacted by a shutdown. State and local officials are still sorting through those plans and all the programs that would run out of money—a complex task given that federal programs will be affected differently depending on a wide range of factors.

The Bipartisan Policy Center, for instance, noted in a report this week that 70% of federal spending goes to programs like Medicare and Social Security that are considered “mandatory” and will continue to be funded. Meanwhile, the Agriculture Department as of Saturday had not yet updated the shutdown contingency plan it developed in 2021. But that plan says that food programs like SNAP and WIC would be “exempted” from a shutdown because it is considered to be “essential Federal activities.”

While that may be the case again, funding for SNAP could still end at some point depending on what Congress does. During the 2018-2019 shutdown, said Chrisup of the Bipartisan Policy Center, Congress reopened the government by passing a stopgap bill to allow spending for 30 days while negotiations continued. However, the 30-day limit applied to SNAP, putting the program at risk if lawmakers had failed to reach an agreement at the end of that time period.

This is the complexity state and local governments face in planning for a shutdown. Funding may continue to be available or the federal government may allow states to dip into unspent federal funds to help pay for programs, according to the FFIS report.

But how much unspent funds states have varies from state to state, said Howard of FFIS. As a result, part of their preparations for a shutdown will need to include determining if a program has prior-year funds available.

Yet another factor in what programs will see their funding shut off, the FFIS report said, is whether it was included in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act or if the spending bill passed last December funded a program not only for this past fiscal year but also the next one that begins on Saturday.

Funding for the Federal Transit Administration in the bipartisan infrastructure act, for example, runs through 2026, so funding for the upcoming fiscal year does not need to be approved again by Congress.