Local Health Departments Are Understaffed. Would Biden’s ‘Public Health Jobs Corps’ Help?

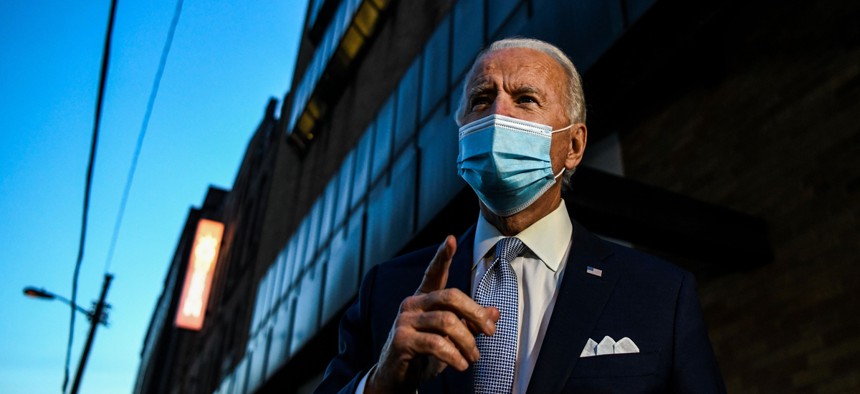

President-elect Joe Biden speaks with reporters in Wilmington, Delaware, on Nov. 24. Shutterstock

Public health leaders say the president-elect’s idea for a corps to help with contact tracing would miss the mark of current needs on the ground, saying they are looking for broader, and more long lasting, federal support.

President-elect Joe Biden is promising a revamp of the federal approach to the coronavirus pandemic, including the launch of a “U.S. Public Health Jobs Corps” to help local departments with contact tracing.

The possible increased funding and support from the federal government is welcome, local public health leaders say. But at this stage of the Covid-19 pandemic, they cautioned that focusing on contact tracing misses the reality of current on-the-ground needs and noted that, given how much effort it would take to build such a program from scratch, the time and money might be better spent elsewhere.

Biden’s re-opening plan campaign page and his transition site’s Covid-19 priorities list both include the promise of a “U.S. Public Health Jobs Corps” to mobilize at least 100,000 people to “to perform culturally competent approaches to contact tracing.” Corps members would be recruited through a partnership between federal, state, tribal, and local governments and “should come from the communities they serve in order to ensure that they create trust and are as effective as possible,” the campaign page reads.

The Biden team did not return multiple requests for comment regarding further details of the proposal. The idea laid out on the transition website is that the corps would be part of a broader effort to bolster testing, including deploying more advanced rapid tests, as well as ensuring personal protective equipment is adequately deployed.

Lori Tremmel Freeman, CEO of the National Association of County and City Health Officials, said the contact tracing job corps might arrive too late as the pandemic surges across the country, overwhelming both hospitals and local health departments.

“We do appreciate that the incoming administration recognizes the workforce needs of this pandemic, but there’s a lot more thought that needs to go into this,” said Freeman. “We are significantly into this pandemic at this point, and the work to create this—recruitment, training, placement, supervision—would require a huge lift.”

Freeman and other public health officials say they want to see more from the incoming Biden administration about how they plan to build up the public health workforce not only to deal with the current pandemic, but to prepare for the next one.

In the past decade, funding cuts have resulted in the loss of 20% of the local public health workforce. The pandemic has only deepened these workforce woes, with people exiting the field as they burn out. According to research by the Associated Press and Kaiser Health News, at least 181 state and local public health leaders across 38 states have retired, quit, or been fired since April 1—a statistic that alarms people like Freedman, who said “the nonstop march out of public health represents so much experience lost with no one waiting in the wings.”

A federal personnel response to the pandemic could likely be rolled out more quickly if the Biden administration built on programs that already exist, rather than creating new ones, Freeman said. The country has a strong network of medical reserve corps—over 190,000 volunteers in nearly 800 local units—that are often tapped to provide care during emergencies like hurricanes or tornadoes. They’ve also worked during the pandemic to provide help with contact tracing efforts and to ensure safe election proceedings at polling sites.

“When you think about a job corps for public health, let’s look at what we already have,” Freeman said. “We could take those existing units and invest in them and build their skills.”

But one drawback to utilizing the reserve corps is the workers might not possess all the skills needed in local health departments. A one-size-fits-all approach won’t work when health departments need so many different kinds of help, including administrative personnel to run mass vaccination clinics, nurses to administer shots, IT experts to manage data, epidemiologists, or translators. Local health departments should be “front and center” in the decision making around investments in public health, given “flexibility, not just people,” Freedman said. “They should go to each health department and ask ‘where are you doing well, what do you need, how can we help you?’”

Aaron Aupperlee, a spokesperson with the Allegheny County Health Department, which includes the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania said that the agency has already built a contact tracing team large enough to handle the volume of work. However, he did acknowledge that more staff is needed for more in-depth case investigations because “the current surge of cases … has maxed out” the department’s investigation capacity.

Like all state and municipal health departments, Allegheny County relies in part on federal funding and would welcome additional help to pay for testing, staff, and PPE, Aupperlee said. “Increased federal investment will ensure these activities can continue and help fund the vaccination programs needed to put an end to the pandemic,” he said.

Across the state in Philadelphia, the department of public health is “not currently hiring or interested in hiring contact tracers,” said James Garrow, director of communications, in large part because there are so many coronavirus cases right now that contact tracing is no longer useful.

Garrow said that perspective could change once cases are more contained. But with more than 100 contact tracers on staff already, Garrow said that the department is instead interested in funding to help with vaccine distribution, which is becoming a priority with vaccines beginning to roll out.

In Seattle, Kate Cole, a spokesperson with the local public health department, said that agency is similarly beyond capacity with their contact tracing efforts and have resorted to sending sick people text messages with infection control guidance. Cole, too, emphasized that the agency’s main struggle is adequate funding for all kinds of initiatives. If Congress doesn’t soon agree on more financial aid for health agencies, the department’s testing capacity, vaccination campaign, and ability to maintain current staffing levels are all at risk.

“Without sustained stable funding there will be wait times for testing, delays in getting results, and increased transmission,” she said. “The opportunity to successfully launch life-saving vaccines will be compromised.”

Despite the struggles on the ground and concerns about funding, some see glimmers of potential hope for the future. While the public workforce shrunk, interest in public health graduate programs skyrocketed, with a more than 300% increase in degrees awarded between 1992 and 2016. The problem, Freedman said, is that these graduates aren’t going into government because they can get better salaries and benefits in the private sector. But the incoming Biden administration could help local governments try to lure these professionals back into the public workforce, she said.

“People love the field, but we need more than these temporary fixes to deal with this problem,” she said. “I’d much rather see the Biden administration address that, rather than build a jobs corps that could come and go. Let’s rebuild the infrastructure so we’re prepared for whatever gets thrown at us next.”

Emma Coleman is the assistant editor for Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: Farmworkers, Firefighters and Flight Attendants Jockey for Vaccine Priority