N.C. eyes cloud for linking statewide property data systems

North Carolina is testing cloud-based tools to integrate its property data silos for a range of uses, including taxation, emergency management and environmental protection.

This article was changed March 27 to correct the number of counties in the United States.

North Carolina is exploring ways to use cloud-based software tools to pull property data from disconnected systems into standard data sets that can be harnessed for a range of purposes, including taxation, emergency management and environmental protection.

The work is part is part of a six-month project, funded by the Environmental Protection Agency, to transform separate county property systems into online data services that can be shared with the EPA’s Environmental Information Exchange Network and with users of the state’s OneMap Geospatial Portal.

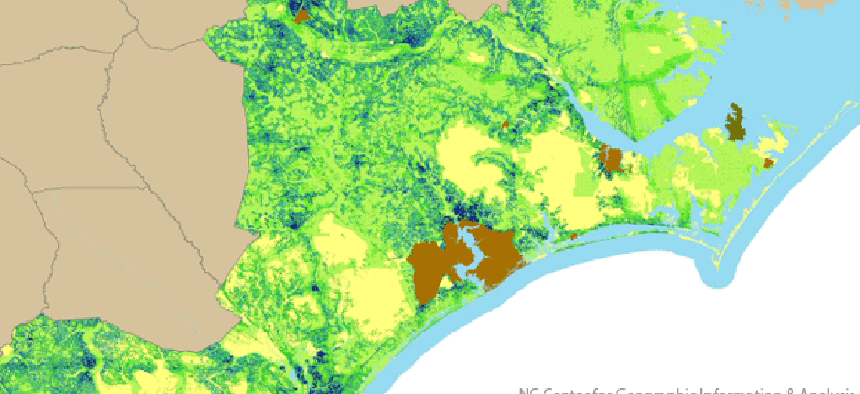

Among other information, the property systems contain parcel boundary data, the precise geographic information system coordinates of a piece of property. When the data is overlaid on top of a satellite or aerial image, it shows a mapped image of the exact boundaries of a lot.

“We have 100 counties in the state and each county builds its own cadastral [property] system within a vacuum,” said Tom Morgan, land records manager with North Carolina’s Department of the Secretary of State. As a result, the data within the systems - which help the state determine land ownership and boundaries -- is not interoperable, making analysis at the regional level almost impossible.

State officials would like to harness that data for more than just determining land size and use and taxes, Morgan said. If all of the county property information was pulled together and made accessible in a single repository, it would have a number of public benefits.

Emergency management personnel could use it to determine what buildings or land are in the path of a hurricane, for instance, or help predict if people need to evacuated and whether assistance is needed from federal sources.

To manage the information, the state sought to set up a cloud infrastructure, where government workers had access to the data they needed in an emergency. In doing so, North Carolina officials brought in the Carbon Project, an Alexandria, Va.-based company that specializes in making GIS and geospatial systems talk to one another.

The company has a set of software tools that translate the counties’ data into a state scheme that can be stored and accessed via the Carbon Project’s cloud, which runs on Microsoft Azure’s cloud platform. Workers using the Carbon Cloud can upload mapping data, transfer it in standard information models and publish it as a service online.

“That is important because the government has dozens of standards to exchange mapping data. However, there are 3,100 counties in the U.S. and most of them use different models,” said Jeff Harrison, CEO of the Carbon Project. “Once you have a service, you can plug any type of app you want on top of that service,” a GIS or mobile app, for example, that supports any mapping standard, he noted.

The company’s CarbonTools PRO provides a unified framework for geospatial interoperability, Harrison said. Developers using Microsoft .NET can therefore add Bing Maps, OpenStreetMap, Yahoo! Maps, Open Geospatial Consortium, Spatial Data Infrastructure, Geography Markup Language, and Esri shapefiles to their development tool sets.

North Carolina is also generating Web services that let the state feed data into the EPA Environmental Information Exchange Network, an Internet-based system used by state, tribal and territorial partners to securely share environmental and health information with one another and EPA.

The EPA collects a lot of data but needs a base map to overlay it on, Morgan said. “Our data connects environmental data to humanity, where people are and how they are being affected” by events, he noted.

Currently, 25 counties are connected to the Carbon Cloud, which is a proof of concept pilot to show the efficiencies associated of moving data to the cloud.

After the project ends in May, state officials are looking to connect 75 more counties to some type of integrated system, whether in the cloud or within the state’s on-premise IT infrastructure, but that decision has not been made yet, Morgan said.

NEXT STORY: Microsoft preps its government cloud