NARA plans online public access to relocated Alaska archives

Connecting state and local government leaders

The National Archives and Records Administration has begun consolidating a number of facilities using storage, digitization and networking technology so it can continue providing access to records that will be relocated.

Pressured by continuing constraints on its budget, the National Archives and Records Administration has begun a program of facility consolidations at a number of sites around the United States, actions that will highlight its use of IT and digitization in providing access to the large volume of physical records that will be relocated.

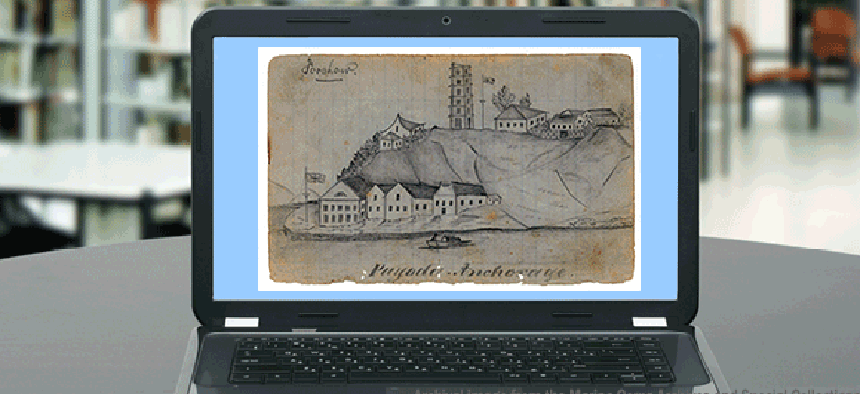

As a part of its most recent announcement, NARA will close a small “storefront” archive in Philadelphia, as well as a similar operation in Forth Worth, Texas, consolidating the two facilities that now exist in both cities to just one in each. The most contentious move, however, is closing the NARA facility in Anchorage, Alaska, which will require shifting more than 12,000 cubic feet of records now stored there to the National Archives records center in Seattle.

The announcements are the result of an effort launched in the wake of the federal budget sequestration that began in January 2013. That forced a review of the 17 NARA archival facilities around the country, according to Jay Bosanko, NARA’s chief operating officer.

“We had to look at each of them and make an assessment about their level of use, the cost to store materials and other factors, and these recent moves were based on all of that,” he said.

The relocation of the Alaskan archives actually reverses what happened in 1990, he said, when the records moved from Seattle to the facility in Anchorage. But the reality now, he said, is that the cost of keeping them there, coupled with the low use of the Anchorage facility, means NARA can service users of the records more efficiently from Seattle.

The goal is to digitize most of the Anchorage records so that a copy of each one can be accessed through NARA’s online public access catalog. However, getting to that point means putting the records through a complicated process, said Pamela Wright, the agency’s chief innovation officer.

“The archival context and intellectual control of the records is very important,” she said. “We have refined processes from an archival point of view of what metadata needs to go with those records, and we have specific technical standards for what level each of the records should be scanned at in order to go into the public access catalog.”

That metadata “is of supreme importance,” she said, since it’s vital to know what file folder a particular item came from before it was digitized, what series of records that folder belonged to and what group it was a part of in order to maintain a hierarchy of context and know what organization created the item.

With that, users will be able to use sophisticated search tools to do both simple and advanced searches of text and pictures, she said. There are also plans to allow tagging and transcription of hand written documents to make the online catalog even more accessible and useful, she said.

What concerns Alaskan users of the Anchorage facility is whether this will be enough to provide for the kinds of research that are done there. The metadata and search terms for the digitized records will have to operate within the context of the local Alaskan communities and cultures.

“I think the priorities for digitizing the records will be very challenging,” said Anjuli Grantham, vice president and advocacy chair at the Alaska Historical Society. "I consult several record groups at a time in my own research projects because many different government agencies such as the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and even NOAA have all impacted Alaska. If they were to digitize just a portion of the records that would provide an incomplete story.”

Also, she said, Internet access throughout Alaska is intermittent at best, and reliable broadband is often unavailable. It can “literally take hours to download a thick PDF document,” she said, so just putting the material online doesn’t necessarily make it accessible to Alaskans.

Wright said that discussions are being held to try and address those concerns, and NARA is exploring different delivery mechanisms and hardware at the Seattle location to make the records more accessible for users in Alaska. The cloud will also be used extensively to help improve access to the records, she said, and the online catalog is being enhanced this year to make it more scalable so it can handle more digital objects.

Conversations have already begun with some of the major archival institutions in Alaska about the move, including libraries, museums and galleries, Bosanko said. NARA is also looking to use online collaboration tools and social media to help with decisions on which records should be digitized first.

The Anchorage facility is due to close by the end of September this year, Bosanko said, but users should understand that digitizing the volume of records contained there will take some considerable time.

Grantham said she and others in Alaska will be taking a wait-and-see attitude to NARA’s plans for Anchorage. They want to see the conversation with stakeholders in the state take place, and for NARA representatives to actually come to Alaska and meet with stakeholders “to show us this is something they are serious about.”

“We want an actual plan to materialize,” she said. “As it is, we have no evidence that (what they’re saying) is anything but lip service.”