Project mines tweets, satellite and drone imagery for disaster response

Connecting state and local government leaders

George Mason University spearheads a DOT-funded project using social media posts, satellites and cloud-based tools to guide first responders to unfolding disasters.

Hurricanes, floods, fires, earthquakes and blizzards can cause massive disruptions to transportation networks and other public safety systems, making it difficult for emergency management workers to know what's happening on the ground when a disaster strikes.

However, first responders might gain a better understanding of an unfolding emergency from a new crowdsourcing project that uses cloud-based tools to help guide satellites and small unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to trouble spots based on posts from social media.

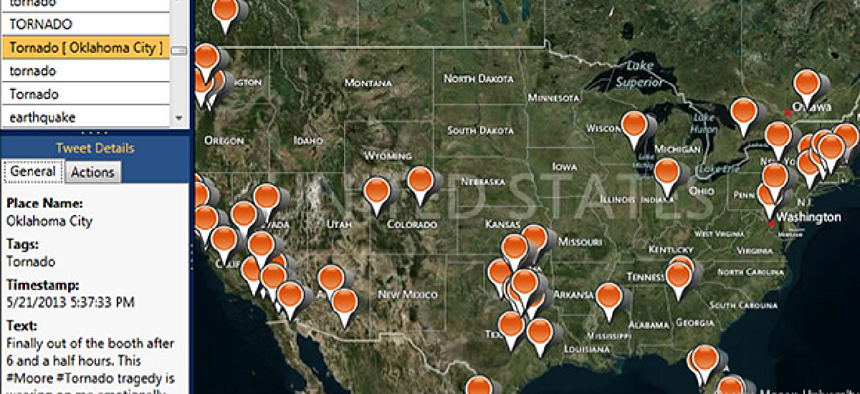

At the center of the project is a geo-social networking application called the Carbon Scanner, developed by the Carbon Project, a software firm that specializes in “geo-social” networking and cloud computing. The scanner picks up on Twitter hashtags related to natural disasters and produces a map showing the location of the tweets so emergency workers can better pinpoint affected areas.

“It’s an alert system that will show where tweets are located and that will hopefully help us define an area where we should be investigating,” said Nigel Waters, the project leader and a professor with George Mason’s Department of Geography and Geoinformation Science, a project partner. After finding the area of interest, satellite imagery could give emergency operations centers a first look at the extent of damage to infrastructure, Waters said.

The tweet does not need geo-location to be picked up by Carbon Scanner. If it does, that’s fine, but the scanner can also detect place names in tweets, such as “flooding at La Guardia Airport” and then put a dot on the map based on that data.

The Scanner mines enough information to get a snapshot of what’s going on at a location during a natural disaster, said Jeff Harrison, CEO of the Carbon Project.

Officials can then fuse satellite imagery with pictures and video from a variety of other sources, including Civil Air Patrols, drones, traffic cameras and citizens, Waters noted. The project participants are using satellite imagery from DigitalGlobal, a provider of commercial high-resolution earth imagery products and services.

The project is being funded by a grant from the Transportation Department’s Research and Innovative Technology Administration. Its partners include George Mason University and representatives from state and municipal transportation departments in Maryland and Westchester County, N.Y.

The project started off with a focus on satellite imagery data, but feedback from the project's advisory group helped bring in airborne imagery from the Civil Air Patrol as well as from drones, Harrison said. Often, after storms or hurricanes, clouds can obstruct the satellite view of what is happening on the ground. This was the situation when heavy rains and massive flooding hit Colorado in September 2013.

In that case, project participants were able to mine data from Twitter and glean imagery data from drones supplied by a Falcon UAV to get a better picture of the effects of catastrophic flooding that devastated the state from Colorado Springs to Boulder County, Harrison said.

Drones will play a big role in providing more real-time information to emergency responders, Harrison, said, especially as the Federal Aviation Administration works to lift restrictions on their use. What’s more, hundreds of small imagery satellites — the size of small refrigerators or big toasters — now being launched by companies such as Skybox and Planet Labs will help government respond to these at trouble spots on the ground, Harrison added.

The Carbon Cloud, which runs on Microsoft’s Azure cloud platform, is essential for the rapid mining and processing of thousands of Twitter feeds, Harrison said. “I don’t know if this [project] qualifies as big data, but it is pretty big data,” he said.

In addition to mining Twitter and imagery data during the Colorado floods, participants in the two year project that ends in August 2014 have conducted a variety of studies assessing damage from Hurricane Sandy, which struck the northeast in 2012; and flooding in Waynesville, Mo., and the city of Calgary in Alberta, Canada in 2013.

NEXT STORY: Do you speak Hadoop? What you need to know to get started.