Western States Negotiate Drought Contingency Plan Despite Wet Winter

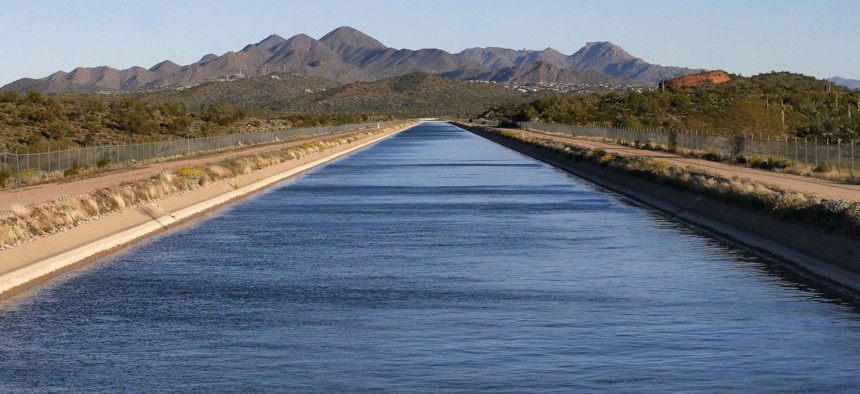

The Central Arizona Project canal near Fountain Hills, Ariz. Matt York / AP File Photo

A visit to Arizona’s Avra Valley highlights advanced hydrological, technological and conservation solutions to the Tucson area’s water concerns.

AVRA VALLEY, Ariz. — Here in the desert 15 miles from downtown Tucson, a remarkable engineering system is providing a reliable supply of water that’s the envy of other communities in the arid West.

Twenty ponds, ranging from 25 acres to 60 acres in size, draw water from the nearby Central Arizona Project canal. These are not reservoirs, but rather facilities that quickly drain into the huge underground aquifers that store enough water to meet Tucson’s needs for the foreseeable future.

Remarkably, the water is cleansed to a high degree of purity as it seeps from the ponds through the earth and into the aquifers. It gets just a small dose of chlorine before dispatch to tens of thousands of faucets in the region.

Wells up to 1,000 feet deep, and powerful pumps, withdraw the water as needed and send it through huge pipes across the Tucson Mountains to the city and its suburbs, and to farmers, Indian tribes and other users.

Over the years, Tucson Water has become a model of responsible water management that has managed to achieve an actual reduction in total water usage despite steady population growth. It has benefited from—and has encouraged—a strong conservation ethic among individual and institutional consumers, the utility’s director, Timothy M. Thomure, said during an interview in his downtown offices.

The Shortage Scenario

Record snowfalls and a lot of rain made the months of November through February one of the wettest on record for the Western United States. A map produced by the National Centers for Environmental Information shows virtually every Western state with above-average precipitation. Nevada and Wyoming had their wettest winters on record, and California its second wettest.

That brought a few sighs of relief in communities where long-running drought conditions have brought restrictions on water use. But among water specialists, there is little complacency, and indeed many expect the long-range trend toward warmer and drier conditions to continue.

Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Thomas Buschatzke recalled in a recent podcast that 2011 was another very wet year, but three years later, drought concerns were back on center stage. “Mother Nature has bailed us out,” he said, “but one good year does not end the drought.”

In the mosaic of water maps generated by expert hydrologists, Tucson occupies a favored place. That’s because of the geological good fortune that produced its capacious aquifers and its focus in recent years on conserving and storing enough water to assure adequate supplies even in the event of the most severe drought conditions. But, said Thomure, “we are never at ease, and we always operate as if drought was around the corner.”

Tucson has been a party to negotiations on a pending Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) that will, once approved, lay out the conditions for water supply curtailment if needed in the three states of the Lower Colorado River Basin—Arizona, Nevada and California. These are three of the seven states that signed a compact in 1922 allocating use of the waters of the Colorado River. Upper Basin States—Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico—were allocated half the river’s flow, or 7.5 million acre feet per year, and the Lower Basin laid claim to an equal amount.

But Arizona needed more than the compact to use the water needed by its fast-growing central and southern cities. It needed a canal. After protracted negotiations, Congress passed the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968, authorizing a $4 billion,100-year loan from the federal government to finance construction of dams and pumping stations and the 336-mile Central Arizona Project canal that now supplies Phoenix and Tucson among other, smaller communities. (Only $1.65 billion must be repaid, according to the CAP.)

In the tough bargaining, California’s delegation held the high cards, and insisted that the Golden State must be granted “senior” rights to the water in the river. As first-priority user, it would be protected from cutbacks in water delivery in the event of shortages in the river. Today, all of California’s 4.4 million acre-feet have seniority rights. Of Arizona’s allocation of 2.8 million acre feet, 1.3 million are “senior” and 1.5 million are assigned the lowest-priority—the price California exacted. Nevada has rights to 300,000 acre feet, most of it supplying Las Vegas.

With drought conditions still in prospect, Arizona officials are negotiating not one but two new compacts. The interstate DCP likely will spell out conditions under which even California will share in cutbacks. The second set of equally contentious negotiations will produce what’s dubbed DCP-Plus—an intrastate agreement among the many claimants to Arizona’s share of the Colorado’s waters. And, a third compact is also under negotiation, between the seven states of the CAP and Mexico, whose rights to 1.5 million acre-feet of of water need extension and addition of provisions to deal with possible shortages in Lake Mead.

A candid and compelling account of the negotiations is found in the podcast recorded by Buschatzke in mid-February. Responding to an interviewer’s questions, project director Buschatzke speaks of four years of “tough” negotiations with many stakeholders. The talks began with all seven basin states participating, but three years ago, the Lower Basin states decided they needed to negotiate first among themselves. Buschatzke says it has been a “very difficult process” with those potentially affected always have “a fear of change.” With the “stakes exceedingly high” the talks have had to proceed carefully, he said.

The talks, and the health of the water supply, revolve around the level of water in Lake Mead, the huge reservoir created by the Depression-era Hoover Dam, 30 miles east of Las Vegas.

As recent photos show, the lake’s surface is far below the dam’s spillway. Full distribution of waters under the Lower Basin compact is possible so long as the depth of the lake is at or above 1,075 feet. It has been flirting with that level in recent years, descending below it at some points, but recovering by year-end when the measurement is taken. At 1,075 feet, reductions will begin. At 1,050, they will increase in severity. At 1,025 or before, Las Vegas will likely lose its water, and conditions for pumping to all recipients will be in uncharted waters, so to speak.

The lake, even with the rains, is only at about at 1,088 feet today. It is less than half full. Another five or six or seven years of heavy rains would be needed to offset the effects of a “15-16 year drought,” said Ted Cooke, general manager of the Central Arizona Project in a recent radio interview.

And the lake suffers from what experts call a “structural deficit.” Thomure said there are two reasons: “the Colorado River is over-allocated relative to its ability to supply water, and evaporation in Lake Mead and Lake Powell (upstream) is not adequately accounted for.” The deficit means that Lake Mead loses about 10 feet a year, equivalent to 600 acre-feet.

“The biggest issue under the law of the river since 1968,” said Buschatzke, “is that California does not take reductions until the Central Arizona Project goes completely dry.” Even though that is a scenario that today’s politicians would be unlikely to countenance, Golden State water usage planners have been relying on the law for a long time, he added. Most everyone agrees that water levels in Lake Mead need to be protected, and thus California is apparently ready to accept measures that would reduce its draw, to that end. Cooke characterized the negotiations as akin to untying the “Gordian Knot.”

The negotiations proceed just as California Gov. Jerry Brown has declared an end to drought emergency orders he imposed during the state’s driest four years in history. The wet winter has particularly affected the Golden State, dumping huge snowfalls in the Sierra Nevada, the state’s key water resource, and filling reservoirs serving both northern and southern regions. “This drought emergency is over,” Brown said on April 7. “But the next drought could be around the corner. Conservation must remain a way of life.”

The 4.4 million acre feet California claimed under the 1968 law amounts to about 10 percent of the state’s annual consumption.

Tucson’s Innovation

The low-lying Avra Desert facilities, protected by electronic and physical locks, are impossible to see, except from the air, or on a visit like the one I was privileged to take last week. My tour was led by Dick L. Thompson, lead hydrologist for Tucson Water, and Andrew Greenhill, intergovernmental affairs manager. I was shown both the Southern Avra Valley Storage and Recovery Project, known as SAVSARP, and the adjacent CAVSARP (C for central). Together, they constitute the largest aquifer recharge and recovery system in the country. Other jurisdictions in Arizona and California use similar technologies to recharge their aquifers, but do not have the extensive potable-water recovery systems that Tucson has constructed since it bought huge amounts of land here nearly half a century ago.

Scarcely a building is in sight in the huge valley; one or two computer control huts and that’s about it. But we see the huge holding/drainage ponds, the mammoth pipes used to transmit water to Tucson, and one of the 74 reservoirs that feed the utility’s 395 square-mile service area. Thompson says this one is 40 feet deep and holds 8 million gallons. One can’t see the precious potable water because it’s protected by a green metal cover.

What I’m witnessing is the outcome of decades of hydrological research and development in Arizona, led for years by pioneering Dutch hydrologist Herman Bouwer and continued by his disciples, one of whom is Dick Thompson.

During our tour, we see water pouring from the nearby canal into one of the holding ponds at a rate of 25,000 gallons per minute. The pond has been filling for a month, and will top out after another three weeks. Some of the 20 ponds fill and drain in two months; others take four months. At the moment, six are not in use; they are drying in the baking sun.

A hard crust lines their bottoms and we witness, at one of the dried-up ponds, a chisel plow operator systematically breaking up the sod to prepare the facility for a new dose of CAP water. Once a year, the pond beds are assailed by what Thompson calls the “Big Ripper,” a plow that goes deeper into the soil. The recharging process is done mainly in the cooler months here, to minimize evaporation in the hot summer sun. Withdrawals are heaviest in the summer months, when farmers, by far the largest users of CAP water, are growing their crops.

Much of the water destined for drinking is pumped up to the huge Clearwell Reservoir in Starr Pass in the Tucson Mountains. From there, it is transmitted downhill through a 96-inch pipe, the largest in the system, to smaller pipes that distribute it to customers across the region.

The 96-inch pipe, crucial to the water program, and about 4,000 miles of additIonal piping, are showing their age, according to Thompson and Greenhill. They are reaching the end of their 50-year expected useful life. Innovative technology—the wrapping of pipes with acoustic wiring—helps detect structural weaknesses, allowing repairs before expensive ruptures occur, “saving us a lot of money,” Greenhill said.

Tucson’s maintenance backlog is one of three key challenges Tucson Water Director Thomure said he faces. CAP, he says, will spend $60 million a year on infrastructure improvements in the next five years, and Tucson will contribute, either with higher water rates or with borrowed money or both.

Another challenge, says Thomure, is to keep water rates low, for individual consumers and for business users like the 29 golf courses that dot the map. Turf on the golf courses, and in schoolyards and elsewhere, are supplied by treated wastewater at a rate of 17,000 acre-feet a year.

The third challenge, Thomure says, is to help fight the perception that Tucson, as a desert community, could run short of water. The perception is not in line with the facts, he says, and dispelling it is key to continued economic development as city officials and business leaders work to attract new corporate facilities in the region.

Indeed, Tucson has years of water supply stored in the Avra Valley aquifers. In the worst-case scenario, if Lake Mead’s waters descend to 1,025 feet, Tucson will be in a much stronger position than Phoenix and other cities that don’t have extensive storage programs. Projections indicate that it can meet water demands through 2050 even if CAP deliveries are curtailed.

But the city shares the concerns of others along the CAP about the plight of the lake some 300 miles distant. So it is actively helping to pursue DCP-Plus. Tucson this year is voluntarily giving up rights to 26,500 acre feet of CAP water, or about 18 percent of its allocation. The DCP program is slated to leave 400,000 acre-feet a year in the lake.

At the same time, Tucson is engaged in an experimental program to store some of Phoenix’s CAP allocation. In this, the third year of the pilot, the Avra Valley aquifers will receive 36,500 acre feet belonging to Phoenix. In a test of the legal framework surrounding the program, Phoenix may reclaim some of the water next year. The water won’t be pumped north; instead, Tucson will simply reduce its own claim on Lake Mead’s water to repay the state’s largest city. It will have charged a fee for its storage services.

The DCP will require about $60 million to implement over a three-year period. Of that, CAP managers have assumed that the federal Bureau of Reclamation will contribute $45 million. The Trump Administration’s “skinny” budget gives little clue as to what to expect, although the Interior Department, which houses the bureau, is slated to take a cut. The money will be used to compensate users that don’t want to simply give up their rights to CAP water, notably including the Gila River Indian Community, which has a large allocation. Thomure says he hopes the CAP will “say thank you” to Washington for whatever it may provide, and use it to mitigate Lake Mead’s problems.

Conservation Imperative

Tucson Water is known for innovation, and has been visited by water experts from distant places, including the Middle East and Australia. Its recharge and recovery operations are of particular interest, but it also is known for a long history of highly effective conservation programs.

Today, the utility spends about $3 million a year on programs to promote more conservation. Some of its roughly 550 staff members provide individual counseling to homeowners or businesses whose water usage seems out of line. The inspectors in this Zanjero program may find leaks, toilets or appliances or showerheads that are water hogs, or outside usage of water that might be curtailed.

The conservation program also offers water-efficiency rebates to consumers: $75 for a low-flush toilet and $200 to help replace old clothes washers, and it helps people install cisterns to capture rainwater.

And the city has adopted a water rate structure intended to discourage excessive use. Water costs $1.55 per 100 cubic feet (CCF) at the lowest level—up to 7 CCF. The rate doubles to $3.00 in the next category—8-15 CCF, and has two more levels, up to $11.75 per CCF.

Tucson is also in the seventh year of a 10-year program to install smart meters, and a network tying them together, allowing rapid response to problems in buildings throughout the system.

All of this conservation work is captured in a simple graph Tucson Water managers proudly display. It shows that despite rising population, both residential water consumption and total water consumption has declined over the past decade. Indeed, the conservation plan’s 2015-16 annual report boasts that “Tucsonans are now using water at the same level as in 1985, while population has increased by more than 226,000 and service connections by more than 75,000.”

Despite its relatively secure position, Tucsonans “always act as if we were in a drought,” says Thomure. “Rarely do we relax. We are always confronted with the prospect of scarcity. So we are prudent.”

Timothy B. Clark is Editor at Large at Government Executive's Route Fifty.

NEXT STORY: Trekking Up the ‘First Road’ in the Last Frontier