Seeking Efficiencies Through Major Upgrades to Portland’s Water Works

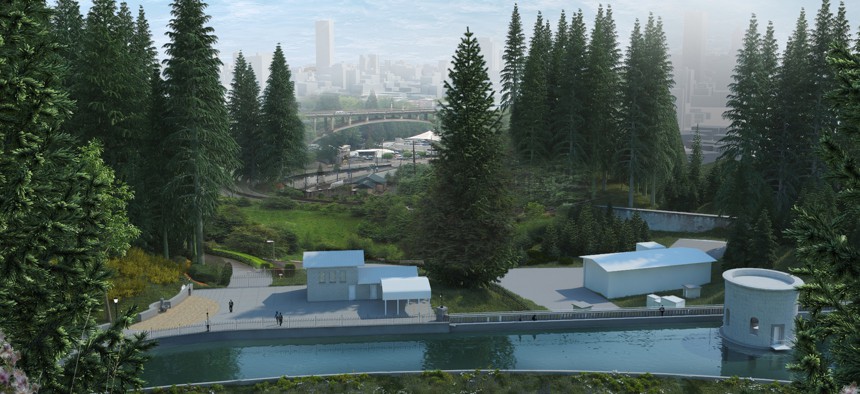

Water systems at the Washington Park Reservoir in Portland, Oregon. Portland Water Bureau

Connecting state and local government leaders

While ratepayers wince, a preference for long-term investment may also deliver long-term quality and some tech advantages.

PORTLAND, Ore. — Local water rate-payers were served with the latest round of bad news in early August when Oregon’s largest city decided on the most expensive, long-term option to add filtration technology to its pristine, Bull Run watershed. Water users in Portland pay among the highest rates in the country, largely because of a decade-long run of major capital improvements kicked off in 2006 when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ruled cities must cover their urban reservoirs.

Since then, the Portland Water Bureau has constructed lengthy water conduits, dug up and reburied existing reservoirs, and replaced aging pumping equipment. Much of Portland’s water, and sewer, infrastructure was built in either the late 19th or early 20th century.

After the City Council’s Aug. 2 decision to spend $500 million on new filtration, the typical household monthly water and sewer charge, already above $100, will rise another $10, according to early estimates.

Unique among American cities, Portland has delivered unfiltered water to its residents for decades, a testament to the cleanliness of its locally sourced supply in the shadow of Mt. Hood. But the EPA and the Oregon Health Authority, which had waived a filtration rule requirement on behalf of Portland since 2012, were forced to rescind that allowance when the Bull Run watershed tested positive for small amounts of cryptosporidium in January of this year. Faced with a decision between a $100 million dollar solution that would blast the water with ultraviolet light, and $500 million dollar filtration solution, Portland chose the latter.

While ratepayers wince, Portland’s preference for long-term investment may also deliver long-term quality, and some tech advantages. The city is one of the few districts in the nation to have taken the first steps to utilize micro hydropower equipment that re-captures energy from piped water flow.

Since 2015, it has incrementally installed mini turbines from Lucid Energy in several of its water mains. Additionally, the PWB set, and has now met, an overall renewable energy target of 400 kilowatts of capacity, utilizing large-scale hydropower at its Bull Run Dam, and, by deploying solar arrays that offset pumping and electricity needs. In 2009, for example, the PWB erected one of what was at the time the Pacific Northwest’s largest solar installations. Today, that array produces roughly 300,000 kilowatt hours (kWh) per year. And the bureau’s total energy usage appears to have flattened, or entered slow growth, even as its system expands, according to PWB data.

This spring, Energy Trust of Oregon awarded an incentive prize to the PWB for its leading edge replacement pump station, designed to save over 2.3 million kWh per year. The historic Fulton pump station, built in 1912—and the single largest source of electricity demand in the system—was replaced with a newly named Hannah Mason station.

According to Blair Hasler, an engineer with Energy Trust’s Production Efficiency program, the new station harvests enormous energy savings in two ways. “First, the old station sourced its water from a lower elevation, and that’s been changed to a higher elevation line. Second, there was a great deal of pressure loss from the old diaphragm type valves, which are now replaced with a butterfly type—a simpler design.”

Hasler noted that just the valve upgrades alone were expected to deliver 14 percent of the total efficiency gain. “Just Google for the two valve types, and you can see the difference,” he added.

According to PWB data, its entire water system was using roughly 20 million kWh per year, as of 2011. Perhaps, for the hundreds of millions in new investment that ratepayers are financing, the city will enjoy a world class water system that’s highly efficient. If so, Portland will jump out ahead of most districts in the country, which are also contending with aging water infrastructure.

But Portland’s not finished. While the first wave of capital improvements has largely come to an end, the second wave is about to get underway. In the first wave, the PWB constructed a new dam tower, invested in water conduits, and rebuilt and covered its large reservoirs sited on prominent local buttes—Powell, and Kelly.

In the second wave, beginning now, the ambitious Willamette River Crossing will be undertaken, and then an eight-year project, the reservoir replacement and covering at Washington Park, will be completed in 2025.

According to PWB, annual capital improvement spending saw a recent peak just shy of $120 million in in 2013, which then fell to $110 million in 2014, $75 million in 2015, and reached a low of $50 million last year, in 2016.

But according to the PWB’s March 2017 budget forecast, capital improvement spending will begin a new ascent this year, rising back to $80 million in 2017 and then hitting double peaks at $120 million in both 2019, and 2021. And those projections were made before early August’s decision to undertake the $500 million filtration project at Bull Run.

The Portland Water Bureau, and the city government, have understandably come under heavy scrutiny for the spending, despite the fact that much of it is driven by federal regulation. A Multnomah County judge ruled earlier this year that the city had misspent Water Bureau funds among a roster of small projects, including a $1.2 million dollar visitor center at Powell Butte Reservoir.

Those funds will be returned to the PWB from the city, but such events drive the public perception that a culture of excess has come to influence project spending. The alternate view is that a number of PWB’s large projects have actually come in under budget since managerial changes took place in 2014.

Moreover, Energy Trust—which was set up by the Oregon Legislature and is funded by fees from ratepayers—acts as an outside institution whose mission is to drive efficiency gains across a number of state utilities from Northwest Natural to PGE.

Susan Jowaiszas, marketing manager with Energy Trust explained: “We are built on the idea that energy saved is even more economical than generating new energy. Our goal, really, is to return the fees we collect in the form of efficiency savings.”

The next mega-project that will surely attract scrutiny is the Willamette River Crossing, a seismically hardened transmission main that will start construction next year. By definition, the pipe will be overbuilt, and most important, redundant.

The project’s entire thesis lies in the risk Portland faces from not a small, but major regional earthquake. But until that earthquake happens, city residents will be quite aware that the newest piece of water infrastructure is merely an insurance policy. Perhaps it’s a necessary insurance policy, however. The July 2015 New Yorker article, “The Really Big One,” which examined the risk of a catastrophic subduction earthquake in the Pacific Northwest caused a sensation.

The writer, Kathryn Schulz, won the Pulitzer Prize for her reporting, and the information that spilled out sparked a frenzy of earthquake awareness from Seattle to Portland. Notable in the story was Portland’s relative geographic isolation.

Under such trying circumstances, having potable water for city residents to drink after a major catastrophe will not seem like a luxury, but a necessity.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to correct the formal name of the Energy Trust of Oregon, not Energy Trust of Portland.

Gregor Macdonald is a journalist based in Portland, Oregon and has written for Nature, Talking Points Memo and The Petroleum Economist.

NEXT STORY: Amazon opens GovCloud Marketplace