Using Nudges and Shoves to Encourage Better Transportation Choices

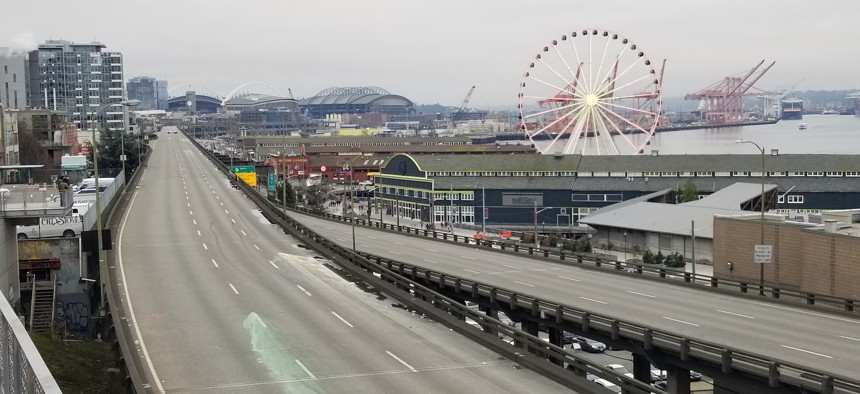

The Alaskan Way Viaduct, which formerly carried State Route 99 along the Seattle waterfront, was closed in January. Michael Grass / Route Fifty

Yes, you can close a major urban highway and the world won’t end.

SEATTLE — It’s been a strange few weeks for commuters in and around the Pacific Northwest’s largest city.

For three weeks starting Jan. 11, one of the two primary highways passing through Seattle’s downtown area, State Route 99, was completely shut down. During this time, the route was shifted from the seismically vulnerable, double-decker Alaskan Way Viaduct along the waterfront to a long-delayed and controversial 2-mile-long deep-bore tunnel, which opened to traffic on Monday.

The so-called “Viadoom,” “Seattle Squeeze” or “period of maximum constraint”—the time between the viaduct’s closure and the tunnel’s opening—was an event long dreaded by state and local officials, with visions of Seattle’s congested commercial core choked in traffic.

So where did the viaduct’s 90,000 vehicles go during the Seattle Squeeze in January? As The Seattle Times reported, they more or less “disappeared.”

Commuters took to trains, buses and water taxi. The city added new bus-only lanes for routes impacted by the viaduct’s closure and implemented further car restrictions along Third Avenue—a major transit spine through downtown—by banning cars for most of the day in an effort to keep buses moving. Bicycle use increased, according to some of the city’s bicycle counters. Many employers heeded appeals by local officials to encourage flexible scheduling or work-from-home options. Commercial deliveries were, in some cases, shifted to the overnight hours to avoid traveling during peak times.

Averting a traffic disaster in Seattle during this period is a demonstration of the power of multiple nudges and an occasional shove—in this case the full closure of heavily trafficked highway without its replacement immediately ready to go into service.

A Focus on Reducing Seattle’s Drive-Alone Rate

Seattle has proven to be an important case study for cities across the U.S. when it comes to transportation. The city is among the few places in the nation where transit ridership has been increasing, especially on buses.

It’s a documented trend that has been featured at numerous national conferences and in plenty of feature articles: When you look at Seattle’s commercial core and adjacent neighborhoods, like booming South Lake Union, the number of jobs increased from 202,000 in 2010 to 262,000 in 2017. Over the same period, the drive-alone rate fell from 35.2 percent to 25.4 percent.

Those stats come from a mode-split survey conducted by Commute Seattle—an organization that works with the Seattle municipal government, transit agencies, the Downtown Seattle Association and local employers to implement programs and strategies that discourage drive-alone commutes into the city center—on behalf of the Seattle Department of Transportation.

In November, during the annual Meeting of the Minds urban sustainability and technology summit in Sacramento, Commute Seattle’s executive director discussed the importance of partnerships and working with employers to encourage commuting options other than driving alone.

“It really is a ratcheting process,” said Jonathan Hopkins, who recently took a job at Lime as director of strategic development in the Pacific Northwest. “It’s all about partnerships.”

Also needed is good data. “We have to know where the needle is if we’re going to move it,” Hopkins said. “If something is important, we measure that.”

Getting employers on board is critical because government can’t lure people out of their cars and onto transit by sheer will. But companies can offer commuter benefits, another nudge for people toward making better transportation choices.

Another nudge has been Washington state’s commuter-trip reduction law, passed in 1991, and follow-up legislation approved in 2006 that requires local governments in urban areas to create programs aimed at reducing the number of drive-alone trips and vehicle miles traveled per capita.

Seattle has benefitted from an expansion of transit service, including the opening of a light-rail extension from downtown to Capitol Hill and the University of Washington. City transportation officials also increased service frequency along major bus routes and created transit-priority lanes to help buses speed through congested corridors.

As a result, Seattle has seen big increases in transit ridership. From 2006 to 2017, it jumped by 46 percent.

“When you get more riders, they will demand better service,” Hopkins said.

During the same panel discussion at the Meeting of the Minds summit, Thomas Stokell, the CEO of Love to Ride—an organization that uses behavior science to help encourage people around the world to use bicycles, pointed out the importance of what he described as the “marine sanctuary” effect.

In the ocean, Stokell said, marine sanctuaries allow protected waters for fish and other sea life to flourish. But those sanctuaries don’t have walls, allowing the stronger populations to travel to new areas, creating a stronger overall ecosystem.

The same is true, Stokell said, when creating places for bicycling, transit and car alternatives to flourish in areas of cities where they didn’t exist before. Once local residents see their neighbors adapting their mode choice, the shift is more likely to spread to others.

With that, there is power in numbers, nudges and peer pressure.

Ahead of the Seattle Squeeze, the Seattle Department of Transportation was dinged a bit by local mobility advocates for not doing more to encourage bicycling as a way to reduce the number of cars heading into downtown. The assumption was that dreary January weather would dampen enthusiasm for bicycle commuting.

But the uptick in bicyclists heading over the Fremont Bridge, which feeds protected bicycle routes heading into downtown, and other bike routes showed the opposite.

"I've never been so happy to be so wrong," Heather Marx, the Seattle Department of Transportation mobility director, said at a recent news briefing, according to The Urbanist, a blog and non-profit organization that promotes sustainable transportation and housing policy.

So, yes, you can close a major highway through an urban area and the world won’t end, as Seattle showed during its recent three-week transportation mode-shift experience, the results of which has rekindled old debates over whether the tunnel was needed in the first place and whether such an infrastructure investment runs counter to the state’s goals to reduce carbon emissions.

For all those lessons recently learned, there’s another transportation reality that’s taken center stage with the State Route 99 tunnel’s opening: induced demand. When the new deep-bore tube under downtown opened this week—it will be free until the summer when variable tolls will be introduced to manage traffic congestion—Seattle commuters showed that they can quickly fill a new roadway.

By the Wednesday morning commute, drivers caused major backups through the entire length of the tunnel and feeding into the so-called Mercer Mess, a notorious chokepoint in the South Lake Union area where drivers are funneled along Mercer Street onto Interstate 5. That in turn impacts some heavily-used bus and bicycle routes crossing Mercer Street.

It’s a sign of potential trouble ahead and a reminder that there’s a lot of work to be done to ensure Seattle doesn’t lapse into a congested mess with the new tunnel.

"Viadoom turned out to be a wildly successful experiment in how to reduce emissions, improve mobility, and better our quality of life,” according to a report released this week by the Move All Seattle Sustainably Coalition. "Understanding why Viadoom didn't happen can help us make future transportation policy decisions with equally happy results.”

Moreover, “Viadoom proved the people of Seattle are ready to tackle the climate crisis, including what needs to happen most: change the way they get around our city,” Rebecca Monteleone, who chairs the Sierra Club’s local Seattle organization, said in a MASS Coalition statement. “We hope that the mayor and the City Council will follow the public's lead and help make this shift permanent. The climate crisis is here and we don't have a moment to lose.”

What comes next? Once tolling starts in a few months, Seattle will learn whether it will be able to make those 90,000 vehicles disappear again. Stay tuned ...

Michael Grass is Executive Editor of Route Fifty and is based in Seattle.

NEXT STORY: State and Local Lawmakers Pitch How to Pay for a Big Infrastructure Package