Climate Change Is Making the Affordable Housing Crunch Worse

Flooded housing in Houston following Hurricane Harvey. Shutterstock

Connecting state and local government leaders

Affordable housing, particularly in coastal areas, is built in areas that are vulnerable to sea level rise and where there isn’t enough infrastructure in place to protect buildings from flooding.

This article originally appeared on Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Last year, right before Hurricane Florence hit New Bern, a small riverfront city along the North Carolina coast, Martin Blaney rushed to the public housing complex he runs, banging on doors, yelling: “Evacuate, evacuate, evacuate!”

When the winds settled and the rains ended in New Bern, Blaney’s nearby offices were under 6 feet of water. Even worse: Nearly half of New Bern’s public housing stock — 108 buildings, all in a flood zone, out of 218 — was under water, too. Twelve buildings were damaged beyond repair. (A nearby public housing complex for seniors, located above the flood zones, was unscathed.)

“We didn’t know the destructive force of deep water,” said Blaney, the executive director of the Housing Authority of the City of New Bern. “It blew us away.

“All of a sudden, you’ve got 108 households that need to have a roof over their head.”

Hurricane season is underway — and storms that make landfall might further exacerbate the nation’s shortage of affordable housing, housing experts say. A new report by Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies said finding enough money to make housing sturdier and fix the damage done by increasingly frequent and severe storms is “an urgent housing challenge for the nation.”

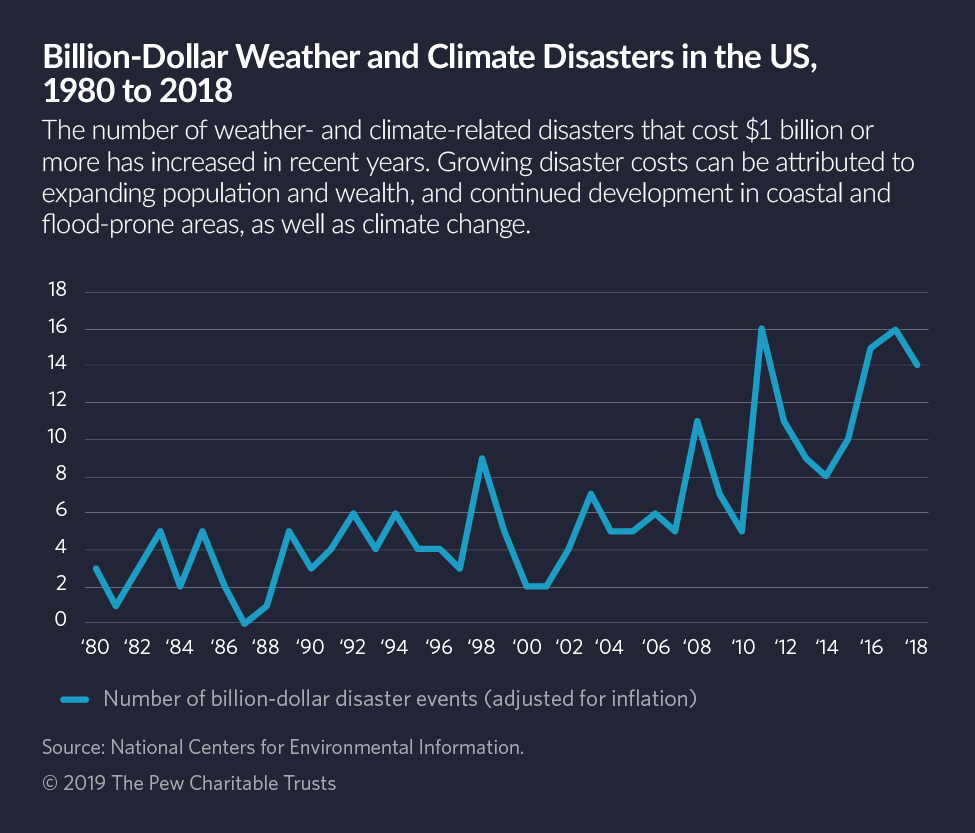

This year alone, there have been six extreme weather events in the form of floods and severe storms across the United States, resulting in losses of more than $1 billion each, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information, a federal agency located within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Hurricane Dorian is heading for the east coast of Florida carrying heavy rain and a potentially devastating storm surge.

Climate change is reducing the supply of affordable housing across the country, said Daniel Kammen, professor of energy at the University of California, Berkeley, and a coordinating lead author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Affordable housing, particularly in coastal areas, is built in areas that are vulnerable to sea level rise and where there isn’t enough infrastructure in place to protect buildings from flooding, he said.

“Under business as usual, we can expect storms and storm surges and [housing] costs to increase dramatically,” Kammen said.

Low-income renters are particularly vulnerable to being displaced by natural disasters, according to a new report by the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank based in Washington, D.C. Affordable housing apartments are often located in flood zones, where the land is cheaper; they’re built with substandard materials that can’t withstand extreme weather; and the buildings are already old and in need of repair, said Heidi Schultheis, co-author of the report.

When damaged by disasters, those units are less likely to be rebuilt, according to a 2017 report by the Hudson Institute, a politically conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C. And federal disaster relief is geared more toward homeowners, rather than renters, Schultheis said.

To be sure, hurricanes have always caused flooding. But they are growing in intensity and frequency. An August report by NOAA found that “it is likely that greenhouse warming will cause hurricanes in the coming century to be more intense globally and have higher rainfall rates than present-day hurricanes.”

That means even more affordable housing will be at risk, Schultheis said.

Disaster recovery doesn’t focus on the havoc wreaked by the combination of extreme weather and the scarcity of affordable housing in communities most likely to experience natural disasters, she said.

The Center for American Progress report recommends that local, state and federal officials invest in programs that reduce homelessness, increase housing affordability and ensure that affordable housing stock is built using high-quality materials and constructed to withstand future disasters.

For example, in Houston, public housing officials are looking into elevating housing located in flood zones or flood-proofing them so water flows around the buildings, rather than through them.

“There’s already a dire shortage of affordable housing,” Schultheis said. “And any damage to that stock is felt so acutely for low-income renters.”

After Hurricane Michael hit the Florida Panhandle last October, 80% of the homes in Mexico Beach were demolished, Al Cathey, the town’s mayor, told the Associated Press. Almost three-quarters of the damaged homes in Bay County, which includes Mexico Beach, were rentals. Four percent of the county’s residents were homeless as of March, according to AP.

Meanwhile, in Houston, since 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, the waiting list for public housing has jumped from 14,000 to 112,000, according to Tory Gunsolley, president and CEO of the Houston Housing Authority.

“We were already full when Harvey hit,” Gunsolley said. “We weren’t able to help all the people who were displaced from housing authority, much less other people.”

And in New Bern, the federal government declared the 108 damaged units ineligible for reconstruction — the cost is too great. The buildings are now slated for demolition, according to Blaney.

Other rental units, mainly privately owned, single-family homes in other parts of the city, have been wiped out as well, he said, adding that he’s had to scrounge to find housing for his tenants, either in private-market units or in public housing in cities miles away from home.

“We’ve got increased demand,” Blaney said. “And decreased supply.”

In August, the North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency announced that it was partnering with the state Housing Finance Agency to provide $16.6 million to build affordable housing developments in Fayetteville and Goldsboro, two areas hit hard by Hurricane Matthew. The funds will be used to build 128 affordable units for low- and moderate-income families affected by the storm.

Meanwhile, this week, the Trump administration announced plans to divert $271 million in funding from the Department of Homeland Security, including the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s disaster relief fund, to pay for immigration courts and Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers.

FEMA did not respond to requests for comment.

Nationwide, there’s a shortage of 7 million affordable housing units for low-income renters, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, a research and advocacy nonprofit based in Washington, D.C.

There’s little available data on the number of affordable housing units that have been decimated by hurricanes and other extreme weather events, because the federal government does not track it well, housing advocates say. But other data provides a glimpse into the scores of renters affected by these natural disasters.

According to data compiled by the coalition, following hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Florence, 3.7 million people in Florida, North Carolina and Texas applied for assistance from FEMA.

Of the 3 million applicants who reported their incomes, slightly more than half (51.4%) reported annual incomes of less than $30,000, while 23% reported annual incomes less than $15,000. About 65% of renters had incomes below $30,000 compared to 37% of homeowners. (The median U.S. income is about $32,000.)

In general, renters are more likely than homeowners to be low-income and struggle with paying for basic needs, according to an October report by the Urban Institute, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington, D.C.

FEMA has not yet posted similar data for Hurricane Michael, and there’s no data available prior to Hurricane Harvey.

Hurricane Maria ravaged Puerto Rico in 2017. About 1.1 million people applied for federal assistance after hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico, with more than 98% of them applying for assistance after Maria, according to data compiled by the housing coalition.

Of the 934,484 applicants who reported their incomes, 79.2% reported annual incomes less than $30,000; 54.9% reported incomes less than $15,000. Seventy-five percent of owners and 88% of renters had incomes less than $30,000. (The median income in Puerto Rico is less than $20,000.)

When a natural disaster like a hurricane batters a community, federal assistance from both FEMA and HUD kick in. But the funds often are restricted to certain programs — or a specific storm. For example, North Carolina, which was hit by two hurricanes within less than two years, has received federal funding from HUD to rebuild after Hurricane Matthew, which occurred in 2017, but is still waiting for funds for Florence, which occurred in 2018.

A 2018 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that when the federal government gave states money to manage their own disaster recovery housing programs, states had trouble running the programs.

Those state-run housing assistance programs can take a long time to launch, said Andrew Aurand, vice president for research with the housing coalition.

The GAO report found that Texas, scrambling with limited resources and staff, often has delays in providing housing assistance to displaced residents. (The Texas General Land Office, the state agency responsible for administering HUD community block grant disaster recovery funds, could not be reached for comment.)

“FEMA is stepping away, and there’s not enough capacity at the state and local level to step in,” Aurand said. “It’s problematic.”

In the event of a natural disaster, FEMA pays for temporary housing in hotels and motels. But often, those hotels require security deposits or credit cards, which can be out of reach for low-income people, said Sarah Saadian Mickelson, senior director of policy for the coalition. A more effective tool, Mickelson said, is HUD’s Disaster Housing Assistance Program, a Katrina-era program that provides housing subsidies to disaster survivors and covers the cost of rent, security deposits and utilities.

Housing advocates have pushed for the program. But while the program is run by HUD, it must be activated by FEMA — and the Trump administration has not done so. Last year, in the wake of Hurricane Maria, the agency said the program was “not necessary to house displaced disaster survivors.”

Before Hurricane Florence, North Carolina had a shortage of 190,000 affordable housing units, according to Laura Hogshead, chief operating officer for the North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency. Now, there’s a shortage of 300,000 units, she said.

“There’s a lack of safe, affordable housing for folks who were storm-damaged,” Hogshead said.

Now, the state is focusing on using federal funds to rebuild affordable housing far from flood zones, Hogshead said. That could mean elevating homes in flood-prone areas so they’re not as vulnerable to getting washed out.

Another possibility: working with state lawmakers to change zoning laws to make it easier to build more affordable-housing, multi-family units in more well-to-do neighborhoods far from flood plains, she said.

“When I was hired,” Hogshead said, “my director said, ‘Please get people out of harm’s way so I don’t have to keep rescuing people off roofs.’”

Teresa Wiltz is a staff writer for Stateline.

NEXT STORY: DOD awards $8B contract for cloud-based business software