What Urban Sprawl Is Really Doing to Your Commute

The interaction of traffic delay and auto commute times is the central force leading to an endless cycle of auto-centric sprawl. Shutterstock

Connecting state and local government leaders

COMMENTARY | Urban traffic congestion is growing dramatically, according to a new report. So why aren’t drivers taking longer to get to work?

A new report from the Texas A&M Transportation Institute about commuters’ traffic woes is a doozy. The big takeaway: Drivers are wasting more time than ever “stopping and going in an ocean of brake lights” (to quote one news account). Since the Institute’s first Urban Mobility Report was issued in 1982, the number of hours per commuter lost to traffic delay has nearly tripled, climbing to 54 hours a year. The nationwide cost of gridlock has grown more than tenfold, to $166 billion a year.

This series of reports has become sort of infamous in transportation circles: It’s been the target of scathing criticism for focusing solely on driving and traffic to the exclusion of public transit, walking, biking, sprawl, pollution, injuries, deaths, or carbon emissions.

But the report’s biggest deficiency is simpler: Commuters are not actually spending all that much more time getting to work.

Take Houston, for example, which according to the Urban Mobility Report has seen the largest increase in congestion delays over the last decade: 75 hours wasted in 2017, up 42 percent from a decade earlier.

Compare that growth with data from the U.S. Census Bureau showing how long it takes Houston drivers to get to work. The average auto commute was 30.3 minutes in the Houston area in 2017, up just 1.6 minutes from a decade earlier—a barely perceptible 6 percent increase.

Houston is not alone. As Figure 1 shows, other sprawling metros experienced big increases in commuter hours stuck in traffic. Still, the average commute duration grew by less than 10 percent, generally 1 or 2 minutes.

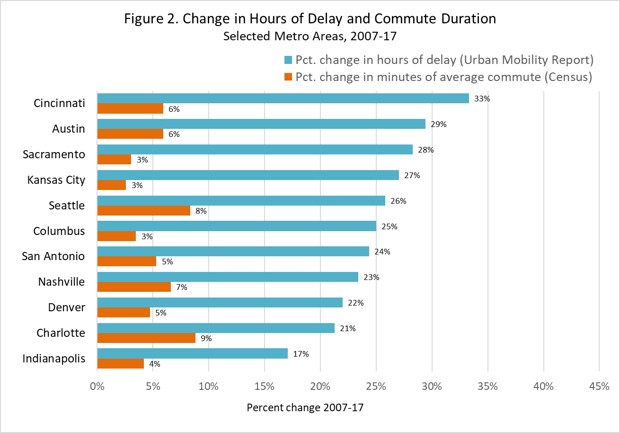

This might seem like a weird statistical fluke. But the interaction of traffic delay and auto commute times is the central force leading to an endless cycle of auto-centric sprawl. Research in the 1990s, 2005, and 2014 documented how suburbanizing metro areas spread ever outward without creating unbearably time-consuming commutes. The process starts when people accept a slightly longer commute into the city in exchange for a suburban house and lawn. Jobs soon follow to the suburbs, shortening the commute for many residents. Some people then move out a bit further to take advantage of cheap land prices and get closer once again to open countryside. As jobs follow again, metro areas expand like a balloon, everyone and everything moving outward from the center but not so far apart from each other. That’s how workers can keep their commutes to a reasonable duration, as shown in Figure 1 for large metros and Figure 2 below for a group of mid-size metros.

(There is a contrasting story in metros that are both fast-growing and geographically constrained, which do see large increases in commute times. The leading example of this phenomenon is the Bay Area, as shown in the detailed table here.)

While commute times barely budge, the commute becomes more stressful, as drivers spend more and more of it in congested traffic. People hate being in those ever-expanding oceans of brake lights, and so congestion becomes a salient political issue. As voters, they demand action.

What to do?

The Urban Mobility Report calls for a “balanced” approach that focuses on “more of everything”—more and wider streets and highways, but also more public transportation, diversified land development patterns, technology, and “realistic expectations.”

Voters seem to be onboard that formula. A host of ballot measures for new sales, income, property and gas taxes to fund transit, often in combination with road expansions, have won approval in recent years, from Tampa to Seattle. (Some, as in Nashville last year, do fail.) Naturally, voters expect something for their money. Transit improvements are thus spread like a thin layer of peanut butter across the region, often in the form of regional light rail systems designed to reach every county or city subject to the new taxes.

Regional transit sounds great at first. And in some places, it’s met the goal of spurring development around light rail stations. I visited the Dallas and Denver areas recently, which have two of the largest light rail systems in the country, and was impressed with some of the results. In Plano, Texas, rail helped catalyze the revival of an historic suburban downtown; in nearby Richardson, new clusters of apartments, restaurants, stores, and offices are emerging along the walkable streets of the CityLine development.

Aesthetically, what I saw in those transit-oriented developments is a world apart from the McMansions and shopping malls of my youth in suburban Chicago. What is no different, however, is their drive-in, drive-out character. They are islands of walkability amid suburban sprawl. You can see the result inside the block-size wrap-around apartment buildings in the new walkable developments. In the middle of the donut, they have two things: a swimming pool and a parking garage, with ample spaces for every resident.

Residents do value having transit nearby—getting to the Broncos game, an occasional trip downtown, or for “just in case” they get a job downtown. And there is always the hope that a whole bunch of other people will take the train and reduce highway traffic.

But they do not use the train very much, if for no other reason than it’s highly unlikely to take them to their suburban jobs. In the marquee walkable developments in suburban Dallas like Plano and CityLine, for example, only a few percent of residents or employees in the area commute using light rail, according to census data. (In some cases, more commuters actually take the bus.)

The Urban Mobility Report says that a set of “balanced and diversified” remedies to congestion can be designed for all different parts of a metro area. The right combination depends on where you are.

But there is really only one solution. That’s to put people—and jobs—back in the core of metro areas. Increasing the thread count in the existing fabric of people and jobs in cities and close-in suburbs will create the conditions that transit needs to thrive: lots of people going every which way, scarce parking, and bad traffic.

A thick urban fabric has been the recipe for successful transit ever since horsecars, cable cars, and eventually streetcars enabled cities to expand beyond a walking radius. From the mid-19th century to the 1920s, these successive technologies connected new housing at the urban edge to downtown white-collar jobs and, importantly, crosstown routes connected blue-collar workers to manufacturing jobs that had recently moved to a ring around the old walking city.

We’ve seen the result of decades of trying out “balanced” metro-wide transportation investment. Even as it calls for more of the same, the Urban Mobility Report also notes that these solutions “have not worked.”

But we do know what will work. It’s what has always worked. Cities. That’s what we need more of.

Bruce Schaller is a consultant based in New York City and the former Deputy Commissioner of Traffic and Planning at the New York City Department of Transportation.

NEXT STORY: States With the Most Cost-Efficient Highways