For Flood-Prone Cities, Seawalls Raise as Many Questions as They Answer

In this Sept. 10, 2017 file photo, waves crash over a seawall at the mouth of the Miami River from Biscayne Bay, Fla., as Hurricane Irma passes by in Miami. AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee

Connecting state and local government leaders

COMMENTARY | Urban leaders and elected officials at all levels of government need to consider carefully before they invest billions of dollars.

The oceans are rising at an accelerating rate, and millions of people are in the way. Rising tides are already affecting cities along low-lying shorelines, such as the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf coasts, where sunny-day flooding has become common during high tides.

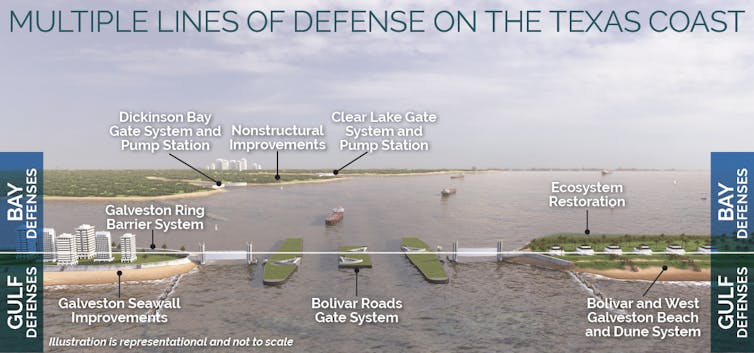

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, whose mission includes maintaining waterways and reducing disaster risks, has recently proposed building large and expensive seawalls to protect a number of U.S. cities, neighborhoods and shorelines from coastal storms and rising seas. Charleston, New York City and the Houston-Galveston metro area are currently considering proposals to build barriers in response to hurricane surges and sea level rise, and the Corps recently published a draft proposal for a seawall for Miami.

As a scientist who studies the evolution and development of coastlines and the impacts of sea level rise, I believe that large-scale seawall proposals raise important long-term questions that residents, urban leaders and elected officials at all levels of government need to consider carefully before they invest billions of dollars. In my view, this approach is almost certainly a short-term strategy that will protect only a few cities, and will protect only selected portions of those cities effectively.

Coastal flooding is here

The extent of high tide flooding in low-elevation Atlantic coastal cities is well documented, and so are future trends. In a 2017 study, the Union of Concerned Scientists assessed chronic flooding risks in 52 large coastal cities and found that by 2030, the 30 cities most at risk can expect at least two dozen tidal floods yearly on average. The study defined tidal flooding as seawater encroaching into at least 10% of a city.

These cities include New Haven, Connecticut; Boston; Philadelphia;, Washington, D.C.; Baltimore; Wilmington, Delaware; Norfolk, Virginia; Charleston, South Carolina; Savannah, Georgia; Jacksonville, Florida; and Miami. Cumulatively, they are home to about 6 million people. The study projected that by 2045, most of them will experience over 100 days of flooding annually.

This flooding won’t just become more frequent – it also will become deeper, extend farther inland and last longer as sea levels continue to rise. Greater encroachment will cause increasing harm to infrastructure, development and property.

The Army Corps of Engineers’ recent proposals include building an 8-mile (12.8-kilometer) seawall around Charleston at a cost of nearly US$2 billion; a 1-mile (1.6-kilometer) wall for Miami-Dade, with a price tag of nearly $4.6 billion; and a 6-mile (9.6-kilometer) barrier to shield portions of New York City and New Jersey, at an estimated cost of $119 billion. None of these investments would protect other Atlantic coastal cities already experiencing high tide flooding.

While these proposed projects differ slightly, they each involve major barriers or seawalls along the shoreline, or just offshore in the case of New York and New Jersey. The structures are intended to protect these areas from hurricanes and storm surges, and from some uncertain level of future sea level rise.

Coverage and Costs

There are a number of key issues that I believe any city considering a major seawall proposal should consider. Here are some of the most critical questions:

– Who and what will be protected by these large walls, and at what cost? With so many U.S. cities already experiencing coastal flooding, and current proposals focusing on very large metropolitan areas, there are important questions about which portions of cities would be surrounded by walls and how much to spend. For example, New York City has a 520-mile coastline, but seawall proposals there focus only on protecting lower Manhattan.

– How many years of protection might these barriers provide, and are they just short-term solutions? Flooding can result from short-term extreme events, such as hurricanes, and also from long-term sea level rise. What time frame should these projects be designed to address?

– Who selects which cities or areas to protect? To date, proposals have come from the Army Corps of Engineers. Which officials and local, state or federal agencies should be involved in making these decisions and establishing policies that will guide responses to future sea level rise?

– Do people really want to live behind walls? In New York, Miami and elsewhere, residents have objected to flood walls that would block views.

– Would these structures encourage additional development behind the walls? Typically, providing flood control encourages new construction in the now-protected area, which increases future liabilities and losses when walls are overtopped or fail.

– What other long-term options should be considered? Boston recently considered flood barriers for either its outer or inner harbor, but rejected these options in favor of softer options like climate-resilient zoning with special requirements for new projects in flood-prone areas.

– Can cities that reject seawalls agree on thresholds or trigger points for taking other steps, such as using some combination of incentives and mandates to move people out of high-risk areas? Norfolk, one of the most flood-prone cities on the Atlantic coast, has developed a plan that prioritizes development in less-vulnerable zones, which it calls “neighborhoods of the future.”

Such decisions will affect coastal communities, infrastructure and residents for decades into the future, and I believe it is time to meet this crisis head-on. Sea level rise is a complex problem with no easy or inexpensive solution, but the sooner the science is understood and accepted, and everyone who is affected has an opportunity to get involved, the sooner cities can make plans. In the long run, there is no way to hold back the Atlantic Ocean.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Gary Griggs is director of the Institute of Marine Sciences and distinguished professor of earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

NEXT STORY: Lighter Pavement Really Does Cool Cities When It’s Done Right