Cutting the Gas Tax Might Be Popular, But It Would Not Provide Much Relief

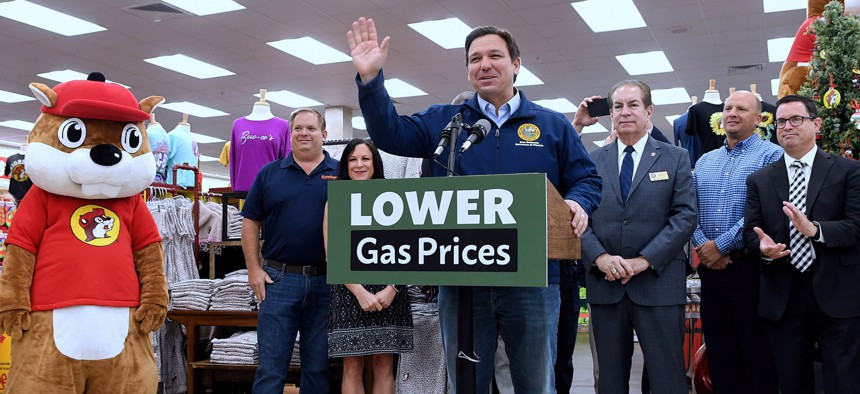

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis speaks at a press conference at Buc-ee's travel center, where he announced his proposal of more than $1 billion in gas tax relief for Floridians in response to rising gas prices caused by inflation. DeSantis is proposing to the Florida legislature a five-month gas tax holiday. Paul Hennessy/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Governors, state officials and Congress are considering rolling back gas taxes, even though experts say customers won’t notice the difference.

With gas prices high and inflation on the rise, particularly because of auto-related expenses, government officials around the country are tossing around the idea of giving motorists a break from gas taxes.

The governors of Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois and Virginia are floating the idea of either rolling back existing gas taxes or preventing scheduled rate hikes from taking effect. Lawmakers and candidates in other states are pouncing on the idea, while the Biden administration is reportedly mulling a national gas tax holiday, too.

The sudden popularity of the idea has made for some whiplash-inducing moments, as officials who only recently staked their political capital on raising gas taxes suddenly saying that now is not the right time to do so.

“Now is not that time,” Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, a Democrat, told reporters about gas tax increases that were part of a bill he signed last summer. “When families are struggling to keep up with costs, now is not the time for the gas tax to keep up with inflation. If that’s a good policy in the long term to help make sure that we have less traffic, and roads and bridges, that’s a fine thing. But now is not the time. Let’s show people relief at the pump.”

As politically popular as the idea is, though, it might not help put much money back in the wallets of motorists.

There are two main concerns: First, that the proposed changes in gas tax rates – sometimes just a penny or two per gallon – won’t add up to much and, second, that changes in the tax rates won’t translate into changes in the prices customers actually pay.

Experts predict gas prices will stay above $3 a gallon nationwide for the rest of the year, the result of high demand and short supply. Changing tax rates will have little effect on those prices.

Oil companies laid off employees and reduced refining in 2020, when Americans briefly cut way back on driving and oil prices plummeted. Since then, though, Americans have returned to the roads while oil companies have struggled to keep up production, said Patrick De Haan, the head of petroleum analysis for GasBuddy, a fuel-price tracking service.

De Haan said it is “significant” that lawmakers, particularly on the federal level, are talking about gas tax relief, because that has never happened before. The federal fuel tax rate of 18.4 cents per gallon has not changed since 1993, even though transportation advocates have long clamored for it to be increased to keep up with inflation.

State-level rollbacks are rare too. The last significant effort along those lines came in 2000, when Indiana and Illinois temporarily suspended their sales tax on gasoline. A 2018 ballot measure to roll back a gas tax increase in California was soundly defeated, with 57% of voters voting against it.

Gas tax rollbacks are likely to have a “negligible” effect on prices, De Haan said. “It may take some time for motorists to see any impact,” he said.

If stations passed along the whole savings of suspending the federal gas tax of 18.4 cents, for example, it would amount to about a 5% reduction on gas prices, or about $2 discount a tank for a passenger car, $3 for a minivan or crossover, $5 for a larger SUV and $6 for a pickup truck, he said.

Most of the proposals at the state level, outside of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ push to suspend his state’s gas tax, would save customers even less.

Plus, De Haan added, “it’s not like you’re going to wake up tomorrow and stations are going to lower their prices by 18.4 cents. … There’s a risk to cutting gas taxes that you’re relying on stations to pass along the decrease, but it’s really up to them.”

Part of the issue is how the gas tax is collected, added Alison Black, the chief economist for the American Road & Transportation Builders Association, a group of road builders. Stations pay the tax when they buy gasoline or diesel from wholesalers, so the tax is essentially just part of the cost of buying fuel. In other words, customers aren’t paying a separate per-gallon fuel tax at the pump.

What’s more, with so many variables at play in gas prices, raising or lowering fuel tax rates has “no significant impact after that first day,” she said.

That’s based on a study Black conducted for ARTBA’s Transportation Investment Advocacy Center in 2020. Black wanted to see whether gas prices really responded to tax changes, in the way that politicians and journalists often characterized them.

“The price change consumers pay at the station has very little to do with any changes in state gas taxes, which are levied to build and repair the roads and bridges they use every day,” Black concluded in the report.

While gas tax rates get plenty of attention, other factors that garner less publicity help determine the price of gas, she said. That includes crude oil prices, refinery capacity, how much inventory oil companies have, what sort of environmental rules apply to the content of gasoline and the demand for diesel for home heating, they noted.

To determine how big of a role state gas taxes played, Black looked at changes in state gas tax rates across the country between 2013 and 2018. It was a period when many states raised their gas tax rates, and others had rates automatically take effect. Black found 113 times that state fuel tax rates changed, including 75 times it increased and 38 times it decreased.

Whether the state gas tax rates increased or decreased, though, the price at the pump changed less than the tax rates did.

The average gas tax increase during that time was 3 cents per gallon. But after the gas tax rates changed, motorists only paid 1 cent more for every gallon.

When gas tax rates decreased, they did so by an average of 1.4 cents a gallon. Again, the price at the pump only decreased by a third of that.

A Matter of Principle

Missouri state Rep. Sara Walsh, a Republican, is sponsoring legislation that would repeal a series of planned gas tax hikes in the state for five years, including a 2.5-cent increase that took effect last year. Two Democratic lawmakers joined the Republican majority to pass the bill out of its first committee.

Walsh opposed the gas tax hikes when Missouri lawmakers first passed it last year. The new law will eventually take Missouri’s per-gallon taxes from 17 cents to 29.5 cents over five years, capping more than a decade of debates over how to improve Missouri’s roads and highways. Lawmakers avoided a provision in the state constitution that would have let voters decide whether to hike the taxes by offering residents a full refund if they collected receipts showing how much they paid.

That’s one of the reasons Walsh thinks the gas tax hike should be repealed. Federal infrastructure money and an influx of other state tax revenues make rolling back the gas tax feasible, she said.

The $7 billion Missouri is expected to receive from the infrastructure law would be “more than enough” to make up the difference from the lost gas tax revenue. “While taxpayers are dealing with inflation skyrocketing to ever-increasing levels, [we need to] provide a little relief at the pump for Missourians,” she said.

“People are mad,” Walsh added. She hears people in her district who are frustrated by the gas tax hike, and 138 of the 200 witnesses who submitted slips at the bill’s hearing supported the repeal. The repeal might not seem like it saves people a lot of money, she said, but “coupled with everything else people are facing,” it can be significant. “Let’s provide people with some relief,” she said.

De Haan, the petroleum analyst for GasBuddy, said the relief would be mostly superficial, but is one of the few options politicians have, because of the limited impact they can have on gas tax prices in the near future.

“It’s like lipstick on a pig,” he said. “It’s something, but it’s not going to cover up how ugly gas prices are.”

Daniel C. Vock is a senior reporter at Route Fifty and is based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: Broadband expansion depends on reliable data