Atlanta’s BeltLine Shows How Parks Can Drive ‘Green Gentrification’

An undated photo shows construction along Atlanta's BeltLine. Ixefra via Getty Images

COMMENTARY | Cities can avoid the problem if they think about affordable housing at the start of their projects.

Is Atlanta a good place to live? Recent rankings certainly say so. In September 2022, Money magazine rated Atlanta the best place to live in the U.S., based on its strong labor market and job growth. The National Association of Realtors calls it the top housing market to watch in 2023, noting that Atlanta’s housing prices are lower than those in comparable cities and that it has a rapidly growing population.

But this is only part of the story. My new book, “Red Hot City: Housing, Race, and Exclusion in Twenty-First Century Atlanta,” takes a deep dive into the last three decades of housing, race and development in metropolitan Atlanta. As it shows, planning and policy decisions here have promoted a heavily racialized version of gentrification that has excluded lower-income, predominantly Black residents from sharing in the city’s growth.

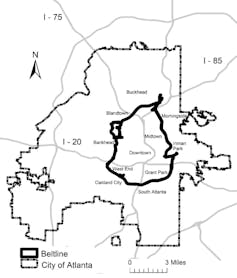

One key driver of this division is the Atlanta BeltLine, a 22-mile (35-kilometer) loop of multiuse trails with nearby apartments, restaurants and retail stores, built on a former railway corridor around Atlanta’s core. Although the BeltLine was designed to connect Atlantans and improve their quality of life, it has driven up housing costs on nearby land and pushed low-income households out to suburbs with fewer services than downtown neighborhoods.

The BeltLine has become a prime example of what urban scholars call “green gentrification” – a process in which restoring degraded urban areas by adding green features drives up housing prices and pushes out working-class residents. If cities fail to prepare for these effects, gentrification and displacement can transform lower-income neighborhoods into areas of concentrated affluence rather than thriving, diverse communities.

The U.S. currently faces a nationwide housing affordabilty crisis. Many factors have contributed to it, but as an urban studies scholar, I believe it is important to learn from Atlanta’s experience.

No more Black majority

U.S. cities generally are diverse places, and many of them are becoming more so. But the city of Atlanta is going in the opposite direction: It’s becoming wealthier and more white.

In 1990, 67% of the city’s residents were Black; by 2019, that share had fallen to 48%. At the same time, the share of adults with a college degree rose from 27% to more than 56%. Median income in the city increased from 60% of the median income of the much larger Atlanta metropolitan area to 110%. Median family income in the city in 2021 dollars nearly doubled, rising from approximately $50,000 to $96,000.

The most rapid gentrification occurred from 2011 onward, after the 2008-2010 foreclosure crisis. Globally, urban scholars call this period one of “fifth-wave” gentrification, in which a large increase in rental demand triggered speculation in rental real estate that drove up housing costs.

In Atlanta, this was when the BeltLine really hit its stride after being proposed in the early 2000s and formally adopted as a tax increment financing district, or TIF, in 2005. In these districts, anticipated increases in property tax revenues are used to front-fund development projects. No urban development project in metro Atlanta – and perhaps in the entire country – has been more transformative.

Driving gentrification and displacement

Even before the BeltLine TIF district was adopted, boosters, developers, consultants and many city officials began touting the benefits of a proposed public-private partnership that could remake large parts of the city. Shortly after the special taxing district for the project was formally adopted, the city of Atlanta created an affiliated nonprofit, Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., to implement and manage the BeltLine.

In 2004, Yale architect Alexander Garvin published a report called “The BeltLine Emerald Necklace: Atlanta’s New Public Realm.” “The BeltLine’s future users are an attractive market,” Garvin wrote. “Early word of the project has already accelerated real estate values.” In 2005, one developer called the BeltLine the “most exciting real estate project since Sherman burned Atlanta.”

Many neighborhoods that the BeltLine runs through, especially on the south and west sides of the city, had experienced decades of disinvestment and were predominantly Black and lower-income. But boosters weren’t worried about investors and speculators buying up land near the BeltLine, and didn’t prepare for displacement and exclusion. Garvin’s report did not mention the terms “affordable,” “gentrification,” “lower-income” or “low-income.”

In a 2007 study for the community group Georgia Stand-Up, I found that property values were increasing much faster near the BeltLine than in areas farther from it. This meant that property taxes rose for many lower-income homeowners, and landlords of rental properties were likely to raise rents in response. This process directly displaced lower-income families and made many areas around the BeltLine unaffordable for them.

The BeltLine TIF ordinance included some provisions for funding affordable housing, but as I show in my book, they were fundamentally insufficient and flawed. The BeltLine was the work of a coalition, including core members of Atlanta’s traditional “urban regime” – elected officials and the downtown business elite. Their vision produced a wealthier, whiter city population.

Noninclusive growth

Rather than focusing on securing land for affordable housing when values were low, Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. prioritized building trails and parks. These features helped boost property values, accelerating gentrification and displacement.

After the subprime mortgage crisis in 2007-2010, foreclosures put pressure on housing markets. Atlanta lost about 7,000 low-cost rental units from 2010 to 2019. Meanwhile, construction of new, pricier apartments boomed: Permits were issued for more than 37,000 units over roughly the same period.

By my calculation, Atlanta’s job market exploded from 330,000 jobs in 2011 to over 437,000 jobs by 2019. Companies like Google, Honeywell and Microsoft moved in, often with city and state subsidies. Many new jobs paid over $100,000 per year and went to young, highly skilled workers, driving up housing demand.

In 2017 the Atlanta Journal-Constitution ran a high-profile investigative series documenting that the BeltLine had produced just 600 units of affordable housing in 11 years – far off the pace required to meet its target of 5,600 by 2030. Some of these units had been resold to high-income households. Soon afterward, the CEO of Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. resigned.

That year, a student and I redid my 2007 study on home values around the BeltLine. Once again, we found that during the years we examined – this time, from 2011 to 2015 – home prices near the BeltLine rose much faster than in areas farther from it. The BeltLine was certainly not the only cause of gentrification and racial exclusion in Atlanta, but it was a key contributor.

Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. has increased its affordable housing activity in recent years, and in late 2020, it initiated a program to pay the increased property taxes of legacy residents. However, by this point in the BeltLine’s existence, displacement prevention efforts may be too little, too late. By May 2021, only 128 homeowners had applied for the program. Just 21 had received assistance.

Putting affordability first

What can other cities learn from Atlanta’s experience? In my view, the most important takeaway is the importance of front-loading affordable housing efforts in connection with major redevelopment projects.

This means assembling and banking nearby land as early as possible to be used later for affordable housing. Cities also should limit property tax increases for low-income homeowners and for property owners who agree to keep a substantial portion of their rental units affordable. They might offer low-cost, long-term financing to existing lower-cost rental properties – again, in exchange for keeping rent affordable.

Some large-scale urban redevelopment projects, such as the 11th Street Bridge Park in Washington, seem to be making serious efforts to anticipate and mitigate gentrification and displacement. I hope that more cities will follow this lead before undertaking “transformative” projects.

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dan Immergluck is a professor of urban studies at Georgia State University.

NEXT STORY: Railroad Tracks Can be an Obstacle for High-Speed Internet Buildouts