50 years later, group asks: What if other urban highways had been built?

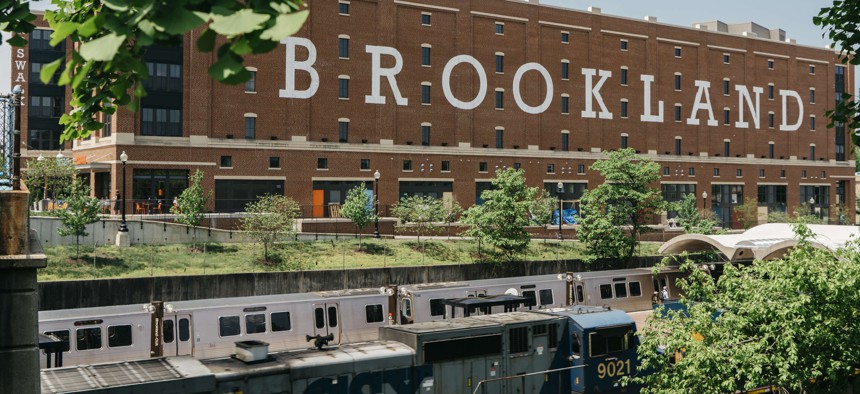

The Brookland Metro station in Washington, D.C., near where a highway was once slated to be built. Justin T. Gellerson for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Highways once slated for Atlanta and Washington, D.C., would have sliced through areas that are now some of the cities’ most vibrant neighborhoods.

In debates over highway expansions, it is easy for advocates to point to examples of highways that were built and how they affected nearby neighborhoods for the next several decades. But what about highways that were considered but ultimately canceled?

That’s the task that a new study by Transportation for America, an advocacy group that pushes for less car-centric development, tried to tackle in a recent study. The report looks at the experiences of Atlanta and Washington, D.C., to explore the contrasts. Both cities built massive interstate highways that displaced thousands of people in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but later halted plans for even more interstates.

The issue of highways’ impact on cities has taken on more significance in recent years, as many urban officials consider tearing down or replacing roads that act as barriers between communities and sources of pollution. The Biden administration is also doling out grants for cities and other groups that want to mitigate the harms from highways in their areas.

Beth Osborne, the director of Transportation for America, said her group’s “Divided by Design'' report shows the lasting impact of the highway building spree half a century ago. Decisions made then still have tangible effects in the communities where those highways are located. But they also influence how current policymakers evaluate and measure transportation alternatives.

The recent efforts to mitigate the negative effects of highways are still treated as “special projects with a small amount of money,” she said, but the bigger highway program still has “inequities at its core.”

“We’re doing [this analysis] so people realize it’s not just past inequities we’re dealing with. We’re dealing with inequities in the current system that continue to cause real harm,” Osborne said.

The group contrasted what happened in neighborhoods where highways were built and where they were not and found stark differences.

The five miles of interstates built through the southern neighborhoods of Washington, D.C., for example, initially displaced 4,700 people. The stretches of I-395 and I-695, in fact, were part of a greater “urban renewal” effort that eviscerated the area southwest of the U.S. Capitol. Those public works projects led to the destruction of 99% of buildings in the Southwest quadrant.

The highways still morph the fabric of the city, funneling automobile traffic toward the Potomac River while separating swaths of the waterfront and other neighborhoods from residents and resources in the north.

The interstates sit on 311 acres of land that would otherwise be worth about $3.3 billion, the Transportation for America estimated using Census data and commercial records. The highway wiped out $1.4 billion in potential home value, enough to generate roughly $7.6 million in just property tax revenue every year.

By comparison, District officials shelved plans to build even more highways through the heart of the city. The ostensible goal of those expansions was to better connect downtown and the Capitol area to suburbs in nearby Maryland and Virginia, but local opposition from both Black and white residents in Washington eventually stymied those efforts.

A plan to add a “Northern Leg” extending Interstate 66 through the city would have separated much of downtown from neighborhoods in the north and west. The area now includes the stately homes and shops in the wealthy Georgetown area, the DuPont Circle area that is home to many foreign embassies, the eclectic Adams-Morgan neighborhood known for its nightlife, the U Street corridor that launched the career of jazz great Duke Ellington and the Shaw neighborhood that is home to Howard University.

All of those areas have seen significant revitalization in recent years, with new condominiums and boutique shops opening regularly, bringing more pedestrians to already teeming sidewalks. Residents rely on buses, bikes, scooters and the Metro to get around, rather than highways.

Another unbuilt highway, called the “North Central Freeway” would have shot north on the eastern side of the city, mostly along existing freight rail tracks. Residents in the Brookland neighborhood along the route protested the plans for “white men’s roads through black men’s homes” and eventually brought the project to a halt.

Today, that corridor is used for the Metro subway system’s Red Line as well as a popular walking and biking trail. Brookland remains a leafy enclave of single-family homes not far from Catholic University, while food halls, bars, breweries, bike shops, a movie theater, a farmer’s market, charter schools and several apartment buildings have sprung up closer to the Metro stations and bike path.

If those highways had been built, Transportation for America estimated, the District of Columbia would have lost $6.8 billion in taxable land value. It would have decreased property tax collections by at least $35 million a year.

Plus, 17,500 residents and more than 9,300 homes are currently in the likely footprint of where those highways would have gone. That doesn’t include nearby homes where residents would likely have been impacted by the highways but weren’t in their 360-foot-wide path.

The area today includes 42 office buildings, 37 apartment or condo buildings and 224 active businesses.

A similar dynamic occurred in Atlanta, the group said.

There, white officials in the area chose a route for the east-west Interstate 20 to separate Black areas of the city from white ones. The 11 meandering miles of the highway through the northern parts of the city consume 572 acres, or roughly $150 million in taxable land, Transportation for America estimated.

The interstate displaced at least 7,500 people in 1960 and destroyed an estimated 2,200 homes, the group said. The average home equity that was lost, if the homes existed today, was $596,000.

Politically powerful white residents, though, stopped the planned construction of Interstate 485, which would have run through wealthy neighborhoods on the city’s east side.

“The interstate would have traveled through or near some of the wealthiest white neighborhoods in the city north of I-20, including Morningside-Lenox Park, Virginia Highland, and Inman Park, where massive opposition helped defeat the project [by 1975],” Transportation for America’s authors wrote.

The Georgia Department of Transportation razed numerous homes and seized land for highway construction, but much of it sat fallow for years before becoming part of the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum, new parkland and a short parkway built in the 1990s, the group noted.

Today, there are more homes but fewer people in the highway’s proposed path than when it was under consideration. The homes there are worth a collective $1.3 billion, which generate $12 million in property taxes every year.

There are also 95 multifamily buildings, 62 office buildings and 199 businesses in that footprint.

Osborne said it is surprising that analyzing the economic impacts of highways that are built or not built is not more common. But it is not a straightforward task, especially when projects can so drastically change the character of a neighborhood.

“In transportation economics, we assume that businesses are just floating around the region looking for a place to land, so if you take this away, they’ll just go elsewhere. That is not how small business works at all,” she said. “We don’t put a lot of emphasis on agglomeration benefits, the notion that once you have an area you attract people to start businesses they wouldn’t have otherwise.”

Highways can sap the vitality of vibrant neighborhoods like Sweet Auburn in Atlanta or Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “There’s a real obliviousness to racist impacts” in highway planning, Osborne said.

Transportation planners’ mindset about highway building affects the way they think about neighborhood roads, too, Osborne said. For example, designers prioritize the time it takes for highway motorists to get to their destinations but ignore the added time it costs people in the surrounding neighborhoods to get where they’re going.

Applying highway standards to local roads also disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic communities.

“Trying to speed service travel between cities on a highway makes sense. When you apply that highway mindset to surface roads, that’s how you create the deadly circumstances that we find on our roadways today,” Osborne said. People of color are more likely to be killed while walking, because they don’t have as easy access to vehicles and because their neighborhoods often have fewer alternative transportation options, she said.

“Getting around their community is not what our standards and performance measures seek. It is getting people through their communities,” she said.

Daniel C. Vock is a senior reporter for Route Fifty based in Washington, D.C.

NEXT STORY: Climate change is increasing stress on thousands of aging dams across the US