Alabama begins rolling out IP network for 911 calling

Alabama's Next Generation 911 system will be one of the first in the nation to move all of the state's 911 traffic to an IP network, opening the door for advanced text, video and data services.

Alabama has begun routing wireless 911 calls over a statewide IP network in the first phase of its Next Generation Emergency Network (ANGEN).

When completed, ANGEN will be one of the first statewide IP 911 routing systems in the nation, cutting costs and improving reliability for traditional emergency voice calls, and laying the groundwork for the use of advanced text, video and data services. The first public safety answering point (PSAP) was put on the network Sept. 30, and by early November seven PSAPs were up and running, receiving wireless calls from T-Mobile, the first carrier connected to the network.

Other national and regional wireless carriers are expected to join the network in the near term, but full operational capability for ANGEN with both mobile and traditional wireline calls at all 115 answering points in the state is probably three years off, said Jason Jackson, executive director of the state’s 911 board.

That will be several years beyond the initial — and ambitious —18-month timeline for the project. But Alabama still will be in select company with one of the first, if not the only, statewide system in the country, said Kevin Breault, vice president of emergency services products for Bandwidth, the project’s 911 services provider.

“It’s a long process to overhaul and rebuild an existing 911 infrastructure,” Breault said. “The technology is the easy part.” Funding and coordinating the shift to new protocols among hundreds of PSAPs and the national, regional and local wired and wireless service providers is the real challenge.

When it is completed, the legacy system of seven selective 911 voice routers from CenturyLink and AT&T will be collapsed into a single consolidated network, the Alabama Research and Education Network operated by the Alabama Supercomputer Authority. It will be served by redundant routers at supercomputer centers in Huntsville and Montgomery to provide resiliency.

When a 911 call is made from a participating carrier it will be directed to one of the two points of presence in Huntsville or Montgomery. From there the call will be routed to the appropriate PSAP. The routing function is provided by Bandwidth. The appropriate PSAP is determined by location information that is forwarded by the carrier along with the call. This information also is forwarded to the PSAP and displayed on a console when the call is received.

Why is Alabama putting itself out on the edge of Next Generation 911 service? “This is something we take a lot of pride in,” Jackson said. “911 and football are two things in this state we take passionately.”

The state has a history of leadership in 911 services, claiming the nation’s first 911 call in 1968 over a local system in the town of Haleyville just a month after AT&T announced designation of 911 as a national emergency number and two weeks before AT&T implemented its first 911 system in Indiana.

More than 40 years later, the state’s circuit-switched copper-wire system was struggling to keep up with telecom advances that included wireless mobile phones and Voice over IP. “We’ve put on Band-Aid after Band-Aid,” Jackson said.

To provide a comprehensive fix, Alabama applied for 911 improvement grants in 2009 under a $40 million program through the Transportation and Commerce departments. Cost was estimated at $460,000 for two routers and about $1.4 million to build out last-mile connections to each of the 115 answering points for a total cost of $1.9 million. The state received $950,000 in federal grants and committed another $950,000 of its own money, largely from a fund established originally to improve wireless 911 capabilities.

Work on the system began in June 2012. Wireless traffic is being moved onto the new system in Phase 1 because it accounts for the majority of emergency calls in Alabama, as much as 70 percent in some places.

“We have T-Mobile on now,” said Jackson, and the other major national carriers, Verizon, AT&T and Sprint, along with the regional carriers, are expected to begin the certification process to validate connections and protocols soon. “By the middle of spring we should be close to having most of the wireless traffic on.”

Phase 2 of the ANGEN transition will begin in early 2014 by bringing in wireline calls, as well.

The first PSAP to tap into the IP network was Etowah County in northeastern Alabama on Sept. 30, followed by the city of Dothan in the southeast part of the state two days later. “Once the first two were done the learning curve was dramatically less, and we are turning them on much more quickly now,” Jackson said. The biggest achievement with the IP network to date is that the call takers can’t see any difference in the service. “Which is a win for us,” Jackson said.

As additional PSAPs, carriers and types of digital media are brought online, the system is expected to move beyond parity with the legacy. One of the first advantages will be the ability to transfer calls easily from one answering center to another. Presently, only those PSAPs that have mutual agreements can transfer calls if one center is unavailable or a call is misdirected. With the digital system, “we can transfer a call anywhere in the state with one click,” Jackson said.

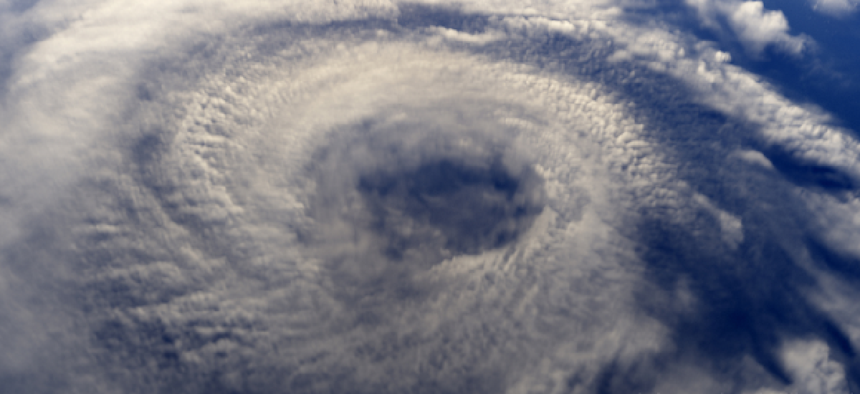

That is a big advantage to a Gulf state that is subject to hurricanes in the south and to tornadoes in the north. During the catastrophic tornado outbreak of April 2011 there were areas of the state that were cut off from outside communications, Jackson said. “It was a good example of why we need to advance to next gen 911.”

The ultimate goal of Next Generation 911 is to combine voice, video, text and data on a single emergency communications platform, to let callers use the services they are accustomed to on their smart phones and other devices when making emergency calls, as well as provide additional information to first responders.

“With the legacy tandem servers we couldn’t take in video or text messages,” Jackson said. Technically that would be possible with the new system, but “we don’t know how to handle it.” He estimates it will be about three years before ANGEN is fully implemented, and incorporation of digital media in 911 services can become a reality.

Full implementation of NG911 nationally will take even longer, Breault said. “It’s a good 10 years away,” although there will be pockets of functionality such as Alabama and smaller regions well before then.

The digital signaling and routing for 911 is not difficult, he said. “What we are doing now is what has already occurred in the commercial world.” But 911 services are lagging the commercial world by 10 to 15 years.

The biggest reason for the lag is that 911 systems are publicly funded. That means money often is tight; budgeting cycles make planning for large-scale projects difficult; and fragmented infrastructure, administration and budgeting complicate large-scale roll-out of new services. But as soon as the plans and budgets are ready, the technology will be available.

NEXT STORY: Police officers get their own private Facebook