Can California Make It Rain With Drones?

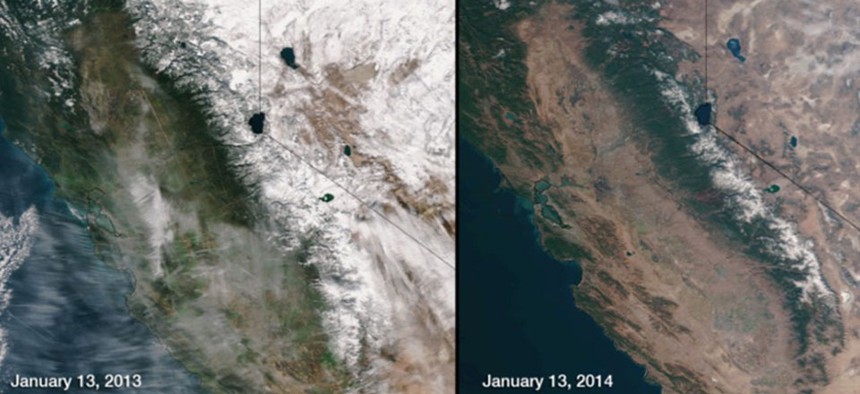

NASA and NOAA released photos of the California drought recently. NASA

Connecting state and local government leaders

Faced with extreme drought, California continues its experiment with weather modification.

Billowy and filled with life-sustaining water vapor, the cloud passes overhead without emitting a drop of rain. In times of severe drought, that cloud is a frustrating, lumbering tease. That cloud is tantalizing. Delicious even.

What that cloud needs is a kick start, a catalyst to squeeze the water out of it. It's not science fiction; it's called cloud-seeding. And in beyond-parched California, it may become a viable option to combat long-term water shortages.

Cloud-seeders can't make rain appear out of clear blue sky. Rather, they create snow (and sometimes rain) where it's most likely to occur—in clouds. Yes, that cloud is full of water vapor, but sometimes, water needs to be coaxed into forming the ice crystals needed for snow (you cansee this happening in this video). The seeding devices, which are mainly on the ground, burn silver iodide into a fine mist that gets tossed up into the air. Silver iodide is an inert chemical (meaning, it won't react chemically with much in the environment), but its structural shape is perfect for seeding ice crystals. Water vapor will collect around the silver iodide and freeze into crystals, then those crystals will precipitate as snow. The snow fills mountainsides, an, come spring, the snow melts and increases the fresh water supply.

The Desert Research Institute operates several such cloud-seeders in California and has found that the process increases the precipitation output of a cloud by around 10 percent—though there is a lot of variability, cloud to cloud, and the effectiveness of the process is debated. In 2003, a National Research Council study found little evidence in favor of cloud-seeding, but because there weren't enough good data on its effectiveness. "This does not challenge the scientific basis of cloud-seeding concepts," the National Research Council assured in its conclusion, calling for more research. "The scientific community now has the opportunity, challenge, and responsibility to assess the potential efficacy and value of intentional weather-modification technologies," the council wrote. A study out of Wyoming is expected to be published in December to more precisely determine the benefit of cloud-seeding.

The California cloud-seeders are strategically placed in its northern mountainous region, where snowpack is an essential component of the yearly water supply. In the past year, the snowpack was depleted to one of its lowest recorded levels. As can be seen in the chart below, much of California's water comes from the snow-laden areas in the northern part of the state.

Not only has the state's snowpack diminished, the ongoing drought in California has gotten so bad that the state is losing mass, as NASA has observed from space. That has wide-reaching implications for a state with a massive agricultural economy. "The water shortage could result in direct and indirect agricultural losses of at least $2.2 billion and lead to the loss of more than 17,000 seasonal and part-time jobs in 2014 alone," reports the National Science Foundation. By 2030, California is projected to have a water supply-to-demand deficit of 1.6 trillion gallons a year, the U.S. Interior Department has predicted.

"Even currently, the supply and demand are somewhat out of balance," Shawn Blosser, an economic consultant with the Blue Sky Group, a public policy consultancy, tells me. "There really is no single silver bullet that is going to solve the problem.

Part of the solution is combating the rising demand for water (Blosser, working with the California think tank Next 10 has developed a menu of policy ideas to reduce demand—the answers aren't easy, or cheap.) But part of the solution is also to increase supply, by cloud-seeding or perhaps a more scalable measure such as waste-water recycling. In all, Blosser and Next 10 project that an increased effort to seed clouds could reduce the looming water gap by 26 billion gallons in 2030, at a cost of $22 per acre-foot of water (325,851 gallons). That's markedly cheaper than other technologies to increase water supply. Water desalination, for instance, would cost $1,890 per acre-foot of water produced.

But seeders aren't a definitive answer to California's water problems. Because they're ground based, if clouds aren't over the seeders to begin with, we're out of luck. Plane-based seeders exist, but pilots can't always fly safely into cloud areas with the highest seeding potential.

Enter the cloud-seeding drone. The DRI is currently testing plans for a cloud-seeding drone program, with the goal of delivering the most effective dose of silver iodide to the clouds with the greatest precipitation potential, wherever they may be.

It may sound like a stretch, but it's important to keep innovating in water resource management. Even if California's drought eases in the next year, Blosser explained, the long-term trend of water demand outpacing supply will continue.

"There has to be a coordinated effort on a lot of fronts to both lessen demand and increase supply, to get the demand and supply back into balance," Blosser said.

NEXT STORY: Virginia Town Uses Unique Approach to Budgeting