America's Streets Are Safer for Drivers, But Not for Pedestrians

BaLL LunLa/Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

U.S. roads are safer than they've ever been for people who travel in cars. But has that come at the expense of those who travel on foot?

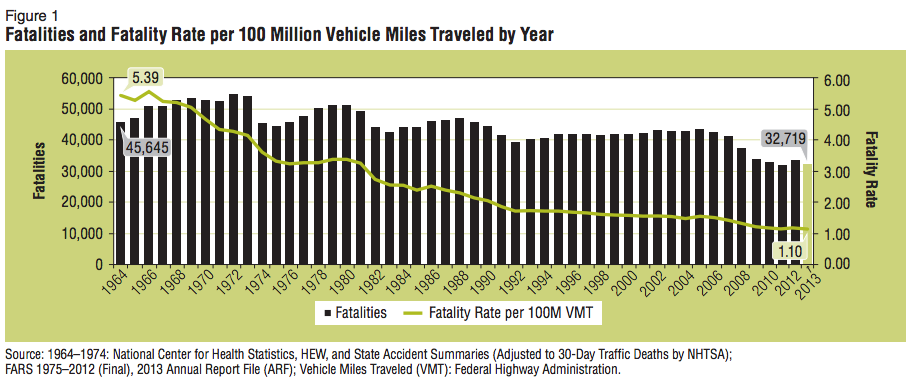

The continued decline in traffic fatalities is one of the brightest trends in public health these days, and according to the latest figures from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, it continued in 2013 , with the overall number of people killed on roads in the United States down 3.1 percent over 2012 numbers. Far too many people still died on the nation’s streets and highways—32,719, to be precise. But that number represents a remarkable 25 percent decrease in traffic deaths since 2004.

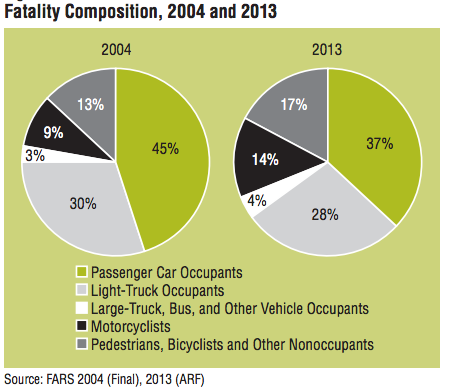

For people outside of cars rather than inside them, however, the news is less reassuring: “non-occupant fatalities” have gone from 14 percent of the total number of deaths to 17 percent over a 10-year period. The raw number of pedestrians killed by drivers did go down down between 2012 and 2013, but by only 1.7 percent, to 4,735. And the longer-term trend is not positive. In fact, pedestrian fatalities in 2013 were 15 percent higher than they were in 2009, when they hit a record low.

As for “pedalcyclists,” the awkward term the NHTSA uses for people pedaling things with wheels, fatalities actually ticked up by 1.2 percent, to 743.

As the Wall Street Journal pointed out in a piece about the pedestrian death numbers, cities have been increasingly turning their attention to redesigning streets and increasing enforcement in the hopes of creating a safer environment for pedestrians.

The efforts to make urban streets safer include initiatives in the nation’s biggest cities. New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles are all in the midst of major traffic-safety pushes that include a very specific emphasis on pedestrians. But in the smaller cities and suburbs of the U.S., the situation for people walking is as bad as ever.

A survey released late last year by health insurance giant Kaiser Permanente suggests that Americans want to walk more. Ninety-four percent of the 1,224 adults surveyed said they thought walking was good for health, and 79 percent said they personally wanted to get out on foot more often. Eighty-seven percent said they thought walking could help ease anxiety and more than 80 percent said they thought it could make you less depressed.

We as a nation may recognize the importance of walking in the abstract, but that doesn’t mean we do much of it. The same survey showed that nearly a third of Americans walk fewer than 150 minutes per week, the threshold established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a minimum for health. And one-third say they don’t walk 10 minutes at one time over the course of a week.

Despite the much-touted rise of “walkable communities” over the last 10 years, the truth is, walking is not built into the American landscape. Forty percent of those surveyed described their neighborhoods as “not very” or “not at all” walkable. When asked what prevented them from walking, fear of cars was at the heart of their response: lack of sidewalks and drivers who speed, text, and talk on their phones were at the top of the list.

This is what it boils down to: A lot of people don’t walk because they are afraid it will kill them before it makes them healthier. And they have good reason to fear.

A quick scan of headlines on any given day will reveal deaths caused by the kinds of structural problems that lead people to choose the relative safety of an automobile for themselves and their families when taking even the shortest trips (only 8 percent of children who live within a mile of school walk there, according to the Kaiser survey).

Those who are on foot, whether by choice or necessity, are leaving themselves vulnerable to often unpredictable motor vehicle operators.

In one horrific pedestrian fatality case, a seven-year-old girl in Springfield, Massachusetts was killed by a drunk driver while crossing the street outside a public library with her mother and a sibling in a spot that was known for being dangerous and where community members had called for a safe crossing place. Because of the library, this was a natural place to cross the street, but engineers had tried to erect barriers to pedestrian crossing and expected people to walk to an intersection far down the street to wait for safety. The convenience of drivers was prioritized, as usual in this country, over the convenience of pedestrians.

“The engineers here have determined that the flow of traffic on this despotic, over-designed urban stroad cannot be inconvenienced by being forced to slow down to a humane speed,” writes Charles Marohn of the nonprofit Strong Towns.”Instead, they erect hedges, fences and other barriers to force the inconvenience on the mother and her two children, who – it should be noted – were walking in the sleet after spending some time at the public library."

Take another example of a mother and child who were struck by a driver in DeKalb County, part of the Atlanta suburbs. They were trying to cross the street to a MARTA station when they were hit by a truck driver. The mother died, and her 11-year-old son was badly injured. As the blogger Atlanta Urbanist points out, there is no crosswalk at the train station entrance and the road has a posted speed of 40 miles per hour. “Pedestrians hardly have a chance when roads like this are engineered for fast car travel,” he writes. “What a tragedy that this happened, but also that this road with a transit station entrance is not set to 20 MPH.”

In one of the most extreme and sad cases of recent years, a mother, Raquel Nelson, was actually convicted of vehicular homicide in Cobb County, Georgia, for walking across the street with her four-year-old son, who was hit and killed by an impaired driver. They had just gotten off a bus at a place where there was no crosswalk, despite the fact that an apartment complex where many bus riders live was across the street. After a national outcry over the case and months of uncertainty, Nelson was at last cleared of the homicide charges and allowed to plead guilty for jaywalking.

As Benjamin Ross wrote recently in Dissent , the same kind of conditions that faced Raquel Nelson are everywhere in America. “Cities like New York, Washington, and Chicago, where people of all economic classes share the sidewalks, are starting to reclaim pavement once abandoned to fast-moving vehicles,” he writes. “But elsewhere, especially in poorer suburbs, the automobile still rules the road. Beneath a veneer of scientific neutrality, traffic engineering operates to the prejudice of anyone on foot.”

The roads have gotten safer for people who can afford to or want to drive. That’s good news. That safety, however, shouldn’t come at the expense of people on foot. Everyone is a pedestrian at some point, if only for a scant few minutes a week. Instead of just wistfully saying that we should all walk more for our health, we need to start building our streets like we mean it, so that walking isn’t instead a life-threatening endeavor.

( Image via BaLL LunLa / Shutterstock.com )