Growing Evidence Shows Walkability Is Good for You, and for Cities

Christian Mueller/Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

New research links walkability with safer, healthier, more democratic places.

There are few issues closer to the hearts and minds of urbanists that walkability. Ever since Jane Jacobs' classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities , urbanists have extolled the ideal of the dense, mixed-used, walkable neighborhood, contrasting it with the dull and deadly cul-de-sacs of car-oriented suburbs.

If walkability has long been an “ideal,” a recent slew of studies provide increasingly compelling evidence of the positive effects of walkable neighborhoods on everything from housing values to crime and health, to creativity and more democratic cities.

A key research advance has been the development of the Walk Score metric (we have written about it here before ), which provides a baseline measure for walkable communities. Walk Score uses data from Google, OpenStreetMap and the U.S. Census to assign any address a walkability ranking from zero to 100 based on a its pedestrian friendliness and distance to amenities such as grocery stores, restaurants, public transit, and the like.

♦♦♦

A growing body of research shows the connection between walkability and housing prices. Earlier this year, economist Christopher Leinberger expanded on his earlier research on “walkable urban places” and found that they have outsize economic impacts . Among the top 30 American metros, these walkable urban places account for one percent of available acreage, but compose as much as 50 percent of the country’s office, hotel, apartment, and retail square footage.

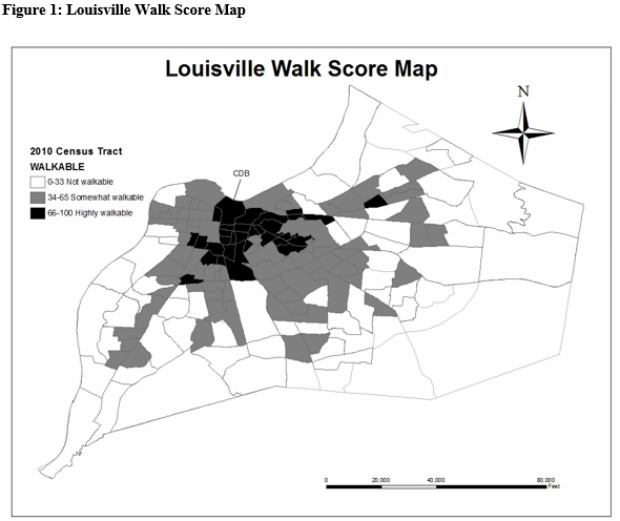

A recently published study in the journal Cities uses Walk Score to reinforce these findings. The study, by the University of Louisville’s John Gilderbloom , California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo’s William Riggs , and Georgia Regents University’s Wesley Meares , examines the effect of walkability on housing values and foreclosures in the wake of economic crises across 170 Census tracts in Louisville, Kentucky. It finds that walkability is statistically significant in predicting neighborhood housing values, and that it is significantly and negatively correlated with neighborhood foreclosures. Between 2000–2006 and 2000–2008, walkability predicated an increase in property values, though the same could not be said of the 2000-2010 period because of the housing collapse. Walkable areas also saw fewer foreclosures in the 2004-2008 period, with highly walkable neighborhoods having 11 fewer total foreclosures. Overall, walkability was almost as important as race in influencing median housing values and foreclosures.

Gilderbloom et al.'s map of Louisville's most walkable places. The most walkable census tracts are in black. (Gilderbloom et al.)

Urbanists have long believed that there is a connection between walkability and crime. Jacobs argued that walkable, denser neighborhoods benefited from “eyes on the street,” or the natural surveillance that occurs in neighborhoods where people are frequently coming and going at all hours of the day. Conversely, criminologists have seen a connection between density, crime, and social pathologies.

Gilderbloom and his team initially found little overall relationship between walkability and crime. But the connection came to the fore when the researchers controlled for the effects of race. Sociologists have long noted the connection between concentrated poverty, race, and crime in urban areas. The study found walkability to be associated with decreased property crime, murders, and violent crime in neighborhoods where minorities made up less than half of all residents. The same held for neighborhoods that were 75 percent white .

♦♦♦

Other research has examined the connection between walkability and health. Medical research shows that walking can improve health outcomes in everything from heart disease and diabetes to improved mental and cognitive functions. But does living in walkable neighborhoods really confer these kinds of benefits?

A separate, forthcoming study by Riggs and Gilderbloom examined the effects of walkability on health outcomes in Louisville between 2000 and 2010. To get at this, they employed, a metric of “years of potential life lost" per 100,000 residents, which measures the difference between life expectancy and the age at which a resident actually dies .

Their study found a statistically significant connection between walkability and health. This effect was even greater in the neighborhoods with the highest concentration of minorities and the poor. As they note, “there are true ‘human costs’ to less walkable, livable environment[s].” Not surprisingly, Riggs and Gilderbloom found health outcomes to be closely associated with both income and race, noting the significant negative relationship between income and years of potential life lost (the poorer you are, the more years of life you’re losing) and a highly significant positive relationship between non-white residents and increased mortality (if you’re not white, you’re more likely to die early).

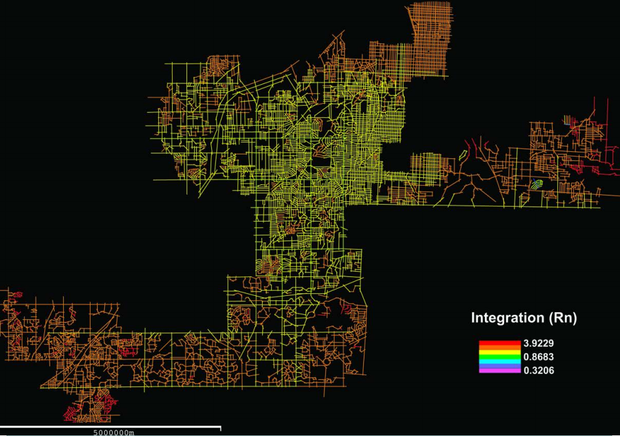

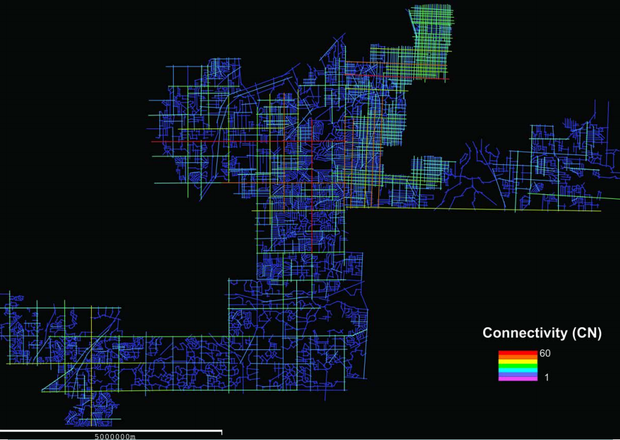

Research from the University of Kansas’ Alzheimer’s Disease Center indicates that walkable cities also have positive implications for cognitive health. The study, by psychologist Amber Watts , tracked 25 people with mild Alzheimer’s disease and 39 older adults with cognitive impairment. Watts found that those who lived in areas of higher “integration," where fewer turns are required to navigate the streets, performed worse on baseline cognition tests and were more likely to see declines in attention and verbal memory. Conversely, those who lived in places with higher connectivity, with more paths and streets linked to each address, performed better on initial cognitive tests and saw fewer declines in attention and verbal memory.

A spatial map of integration. The most integrated areas, in red, are those that provide walkers with fewer path options. Watts' work found associations between highly integrated places and cognition declines in older residents. (Farhana Ferdous, KU Dept. of Architecture).

A spatial map of connectivity. The most highly connected paths, in red, are those that are linked to many streets, giving walkers many path options. Watts' work found associations between a place's connectivity and better performance on cognition tests among its older residents. (Farhana Ferdous, KU Dept. of Architecture)

“There seems to be a component of a person’s mental representation of the spatial environment, for example, the ability to picture the streets like a mental map,” Watts said in a statement. “Complex environments may require more complex mental processes to navigate. Our findings suggest that people with neighborhoods that require more mental complexity actually experience less decline in their mental functioning over time.”

♦♦♦

Denser, more walkable urban environments have also been said to spur more social interactions of the sort that encourages creativity, as well as higher levels of civic engagement. A forthcoming study by my former Carnegie Mellon student Brian Knudsen of Urban Innovation Analysis, Terry Clark of the University of Chicago, and my colleague Daniel Silver of the University of Toronto examines the connection between walkability, creativity, and civic engagement in the U.S., Canada, and France. The researchers examined the effects of neighborhood density, connectivity, housing, age diversity, and walkability on arts employment and the incidence of what they dub “social movement organizations," or SMOs. (SMOs include groups advocating for environmental and human rights issues, among others.)

Their findings are striking. Walking is associated with higher levels of arts organizations, creativity, and civic engagement. In fact, walkability is more closely linked with both the arts and SMOs than variables like density and housing age diversity. “In our results, walking appears as one of most powerful drivers of creativity,” the researchers write. They also find that walking enhances the connection between creativity and civic engagement:

[W]alking, the arts, and social-movement activism are not only separate processes. They enhance one another. Walking amidst the arts appears to heighten imaginative openness to new social and political possibilities, energizing SMO activity more powerfully than walking on its own. Walking is important, but not all walking is the same, and when it occurs in locales with more arts activity, its impact on SMOs is greater.

Walkability is no longer just an ideal. The evidence from a growing body of research shows that walkable neighborhoods not only raise housing prices but reduce crime, improve health, spur creativity, and encourage more civic engagement in our communities.

( Image via Christian Mueller / Shutterstock.com )