The Unexpected U.S. Capital of Unintended Pregnancy

Shutterstock.com

In Delaware, a surprisingly high number of women get pregnant by accident. Here's what it can teach the rest of the nation.

CAMDEN, Del.—Inside a squat building in this town of 3,500 people just outside the state capital of Dover, six high-school students sat around a table last week, each holding a stack of small laminated cards. One girl had her spare arm wrapped around her 5-month-old daughter, who was glancing around in that startled way that only babies and small birds can.

Michelle Freedman, a representative of the local food bank, led the students in an exercise. “This game is called ‘What’s in my pantry?’” Freedman explained. “This going to be just like Top Chef , except it’s what happens at the end of the month when your SNAP has run out and your WIC has run out.”

This session served as a health class of sorts for students of the Delaware Adolescent Program Inc., a network of three schools for pregnant teenagers and those who have recently given birth. Delaware has the highest rate of unintended pregnancy in the nation by some measures, and the reasons why are evident in some of the DAPI students’ life stories: rough childhoods, misinformation, and unpredictable access to birth control.

By the time girls arrive at DAPI, their lives are too complicated for the standard health-class self-esteem pep talks. For them, it’s time to get down to brass tacks—like how to stretch a skimpy food budget as a single mom. DAPI frequently invites guest speakers, such as Freedman, to provide real-world tips.

The girls flipped their cards over. Each card had a food item scribbled on it, and together they represented the only hypothetical products she could use until her next welfare check came. Most had been dealt an unhappy hodge-podge to the tune of “lentils, apricots, pasta, and beets.”

The girls flipped their cards over. Each card had a food item scribbled on it, and together they represented the only hypothetical products she could use until her next welfare check came. Most had been dealt an unhappy hodge-podge to the tune of “lentils, apricots, pasta, and beets.”

One girl groaned. “My family is going to starve,” she joked.

Brooke, a soft-spoken blonde, said she would prepare an impromptu tortilla soup out of her chicken broth, tortillas, and salsa. Her prunes she would eat for breakfast.

Freedman nodded with approval. “Next time you think, I’m going to call Domino’s and spend money I don’t have , think about this,” she said.

Not all of the girls in DAPI are on food stamps, but many are. The program, which runs on donations, arms them with the resources they need to graduate, like on-site daycare and help from a social-services coordinator. DAPI staffers pick students up from home in the mornings, drive them to their doctors’ appointments, and understand if they’re running late because of morning sickness. All of the classrooms have bathrooms attached, because as Camden DAPI director Eileen Wilkerson told me, you’d be surprised how often a pregnant or nursing teen might need to use one, and how uncomfortable it can be to repeatedly ask for the bathroom pass in a regular public school.

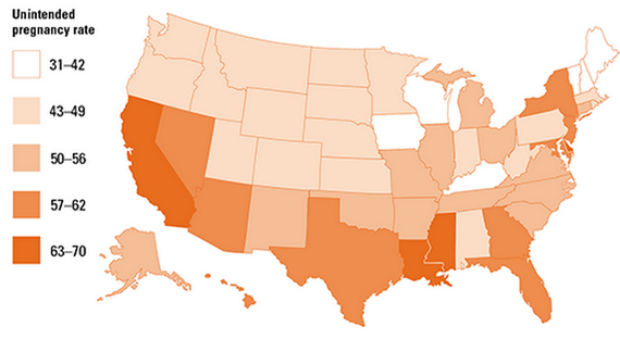

The First State is also first in unintended pregnancies according to the Guttmacher Institute’s 2013 data . In 2008, the year the survey was conducted, 70 out of every 1,000 Delawarean women got pregnant by accident. That number isn’t limited to teenagers—the survey included women aged 15 to 44—but teens are a major driver of unplanned births.

Many children who began as unplanned pregnancies grow to be just as well-loved and cared for as their meticulously timed peers—the babies of the DAPI students exemplify that. But even the most dedicated teen mother might say she wishes she’d delayed her pregnancy by a few years. Reducing unplanned pregnancy is something Republicans and Democrats can agree upon. On the plus side for conservatives, there’s no need for a woman to consider having an abortion if the unwanted pregnancy never happens in the first place. And unintended pregnancies cost Delawareans alone $52 million a year, since many such births are covered by Medicaid.

Meanwhile, liberals note that delaying childbearing improves a woman’s chance of graduating from college and earning a good salary. Children of what theBrookings economist Isabel Sawhill calls “drifter” parents, who slide into childbirth, tend to fare worse than those of “planners,” who make a conscious choice to procreate. Planners’ children get Mandarin lessons and organic baby food. Drifters’ children, whose mothers frequently struggle to escape poverty, get ersatz canned-chicken dinners because the WIC has run out.

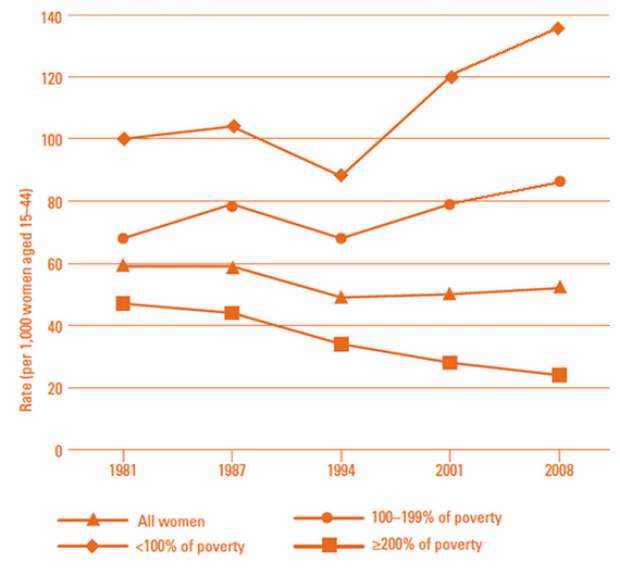

Rate of unintended pregnancy among women of various incomes. ( Guttmacher Institute )

The ranks of such “surprise” children have been rising among poor women since the mid-1990s. Half of all children delivered by women under the age of 30 are born outside of wedlock, as Sawhill wrote in the New York Times in 2012, and 70 percent of those pregnancies are unplanned. As famous Delawarean Joe Biden might say, “That’s a big fucking deal.”

* * *

When I first told my editor that Delaware had the highest rate of unplanned pregnancies in the nation, the resounding reaction among everyone who overheard was “Really?” Delaware doesn’t have any of the typical health-reporter red flags: It has a low uninsured rate, a low poverty rate , and fairly liberal reproductive-health politics. “Unintended pregnancies” conjures visions of a poorer, more conservative place, more along the lines of Mississippi (which is actually #3 by this Guttmacher measure). Or Nevada, which has the Vegas factor (it's #13). Really, anywhere but Delaware.

Unintended pregnancies per 1,000 women, according to 2008 data. ( Guttmacher Institute )

But no, Delaware it is, because Delaware—for all of its smallness and nondescript-ness—has an unusual confluence of factors that add up to a surprising rate of mistimed conceptions. And though this specific cocktail of issues is unique to Delaware, each ingredient has something to teach other states that are striving to make each baby an intentional one.

1. Transportation

Several Delawareans told me that one reason it can be hard to get to a clinic for birth control—or, hell, to a CVS for condoms—is because many parts of Delaware are rather remote and public transportation is spotty. At this, I rolled my eyes a little. (I’m from West Texas, where “remote” means driving through a desert for three hours with a bladder full of Diet Pepsi and no carbon-based life forms in sight.)

But they’re right. Driving to DAPI from Washington, D.C., I first inched my way through the usual teeth-gritting Beltway traffic, then traversed some moderately packed Maryland highways and a preposterously long bridge. After that, though, I felt like I was in a car commercial, swooping down two-lane roads that sliced through barren fields. Closer to Camden, the landscape was interrupted by the occasional mobile-home park or gas station, but still, this clearly isn't the kind of place where one can take the Metro to Planned Parenthood. For a state that, on a map, looks like it was crammed into Maryland at the last minute, it turns out Delaware is not very crammed at all.

DAPI’s Wilkerson told me that the biggest item on her wish list is another van to ferry students and their children to class. When she first started at DAPI, the program had two 16-passenger vans and two drivers. Every morning, one went north and one went south, rounding up students who would otherwise be stranded in their far-flung hamlets because they couldn’t afford cars. The Camden DAPI campus alone had 30 students and a waiting list.

But a few years ago, the organization’s transportation budget was slashed, and now the school enrolls only about 10 students at a time. Granted, there are three DAPI locations, but altogether their student body is tiny compared to the size of the need.

“We do not have a very mature mass transportation system [in Delaware] at all,” said Judith Herrman, a nursing professor at the University of Delaware. “For people who are transportation-challenged, if it’s 40 minutes away, it might as well be three hours away.”

2. Inconsistent Sex Education and Birth Control

Ten years ago, Ellen Zaccardelli was a cheerleader and straight-A student in Dover who thought she was invincible. She was also in the dark when it came to reproductive health. The birds-and-bees talk at her house, she says, was simple: “Don’t do it.”

One night, she and her boyfriend figured they’d try having sex without a condom; they had done it once before, after all, and it had been fine.

This time, it wasn’t. The last cheerleading event she attended was a bittersweet banquet: She was honored with an award, but she was already pregnant and knew she’d never do another backflip in her school colors.

Later that year, Zaccardelli’s daughter, Brianna, was born, and she herself graduated from DAPI in 2007.

Now a mother of four and married to her high-school sweetheart, Zaccardelli recently joined DAPI’s staff as a nurse and maternal educator. She implores the DAPI students to try to avoid getting pregnant on accident again.

“I’m planning to do something with them about the cost over the years of having children,” she said. “You gotta slow down and focus on the child that you have.”

Zaccardelli’s experience reveals some of the misconceptions teenagers have around pregnancy. A study published this year in the Delaware Medical Journal found that, among young women in the state who got pregnant without meaning to, the most common reason was not a lack of access to birth control. It was believing that they would not get pregnant. Ruth Lytle-Barnaby, the president of the state’s Planned Parenthood, said she frequently hears local teens say things like, “I didn’t get pregnant the first time, so I didn’t think it was possible.”

Delaware mandates comprehensive sex education in schools, but the extent to which students learn about contraceptives depends on the preferences of the individual school district. In 2011, the state's schools rolled out two new reproductive-health programs—“Making Proud Choices” and “Be Proud! Be Responsible!”—which include exercises like a mock negotiation where one student must try to convince another not to use a condom, and the second student's role is to try to resist. Because the school system is targeting the most at-risk zip codes first, however, only about 1,800 of the schools’ 35,000-some middle- and high-school students completed the program last year.

Christine Miller, who supervises health and physical education for Delaware’s Red Clay Consolidated School District, said teachers struggle to pack all of the birth-control knowledge into the one semester of health education that the state’s high schoolers get. Budget cuts have made that even more difficult.

The situation might improve in coming years: There are now 26 health centers based in schools around Delaware, and 15 of them provide hormonal birth control on site. The state’s abortion rate has already slid down from 33 per 1,000 women in 2007 to 31 in 2008.

But these and other clinics require teens to obtain a parent’s consent before they can get birth control—a hurdle that can prove formidable. Jennifer Ramirez-Vasquez, a 17-year-old DAPI student, smiled sweetly as she told me that her 18-month-old son, Elijah, wasn’t exactly planned, but he wasn’t not planned either. She and her boyfriend were in love, but her parents strongly disapproved of both the boyfriend, who was four years older, and of Vasquez getting on birth control. Maybe if they got pregnant, the couple thought, Vasquez’s parents would have no choice but to accept their courtship.

To be honest, it kind of worked out. They’re now married. Vasquez was collecting WIC while she was pregnant, but she works hard. She’s graduating high school a year early and already has a summer job lined up as a breastfeeding consultant at a local hospital. In the fall, she’s going to Delaware Tech to study nursing.

That speaks to another important quirk in tallying unintended pregnancies: Sometimes a mistimed pregnancy is actually deliberate, just not for the reasons you’d expect.

“To some people, getting pregnant unexpectedly is not the worst thing in the world,” Herrman, the nursing professor, said. “Does ‘unintended’ mean you won’t be upset that you got pregnant, but you’re not really trying to?"

Vasquez has one especially pretty friend whose boyfriend was fed up with all the attention she attracted from other guys. He got her pregnant in an attempt to keep her for himself. The opposite scenario—where girls try to “trap” their boyfriends with a surprise baby—is also not unheard of.

But most of her former classmates do know about birth control, Vasquez said, adding wryly, “Some of them use me as birth control.”

3. Poverty

When I asked Delawareans why their state had so many unintended pregnancies, several quickly (and understandably) made a pretty obvious joke: There’s nothing better to do in Delaware than bonk. There’s the movies; there’s roaming aimlessly around Walgreens. It’s not quite a cultural smorgasbord.

The problem is, this isn’t a convincing explanation for unintended pregnancy. First of all, unplanned pregnancy doesn’t happen when people have a lot of sex. It happens when people have a lot of unprotected sex.

Besides, as Jane Bowen, program manager for Delaware’s Adolescent Resource Center, told me, “High school students say it’s boring in Delaware, but it’s boring in Idaho, too.” And Idaho’s unintended-pregnancy rate is one of the country’s lowest.

Like others, Candice Pinder, a DAPI student who got pregnant in ninth grade, suggested that partying is the reason why so many of her classmates get pregnant unexpectedly. “Our generation wants to party, have sex, and drink,” she said.

Taken as a whole, Delaware’s “risky behavior” data isn’t especially indicting, however. About half of Delawareans have sex in high school, more than in neighboring New Jersey or Maryland, according to the 2013 CDC Youth Risk Behavior survey. However, young Delawareans are more likely than average to use birth control, and they’re about as likely to drink or use drugs before they have sex as any other teens.

Instead, it seems like risky behavior is part of the problem, but it’s concentrated among a relatively small subset of Delawareans: the poorest ones.

Nationally, the rate of unintended pregnancy is five times higher among poor women than it is among rich women, and Delaware seems to be no exception.

The majority of DAPI students, Wilkerson tells me, are low-income. “Most come from single-parent families. They’re unattended at home, so the parents are not able to monitor what’s going on. Or some are in foster care.”

In Wilmington, the largest city, a quarter of population lives in poverty—a much greater percentage than in the surrounding areas. The teen binge-drinking rate is also higher in Wilmington than in the rest of the state. The city sits right between Baltimore and Philadelphia on I-95, which has become a drug corridor in recent years. Wilmington has more sexually active teens than the state’s other two counties, as well as the state’s highest teen birth rate .

As Bowen puts it, poverty not only surrounds young people with drugs, alcohol, and the potential for sexual abuse, it also clouds “their vision for a productive future.”

“When a strong message is sent that families don’t have the resources to send their kids to college, the social norm encourages parenting at a young age,” she said. “When women have career goals, they’re more likely to adhere to contraception. Racism and poverty play a big role in young females not being motivated to use contraception because they don’t see a future for themselves.”

4. Population

In that way, Delaware’s unintended pregnancies tread the same path as those in other states. One thing that’s different about Delaware, though, is that it’s so tiny. And ultimately, its size might be what’s sending it to the top of the inadvertent child-bearing charts.

“Because Delaware is so small, just three, four, or five pregnancies can skew our numbers,” said Emily Knearl, communications section chief for the state’s health department.

Non-Delawareans agree.

“One of my theories is the so-called ‘D.C. theory,’” explains Bill Albert, the chief program officer for the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. It goes something like this: Whenever the District of Columbia gets ranked with the 50 states, it comes out looking like it’s the worst at whatever that ranking is. ( Poverty , for example, and actually, unintended pregnancy too.) But that’s because D.C. is a city, and cities often have higher poverty, crime, and disease rates than suburbs and rural areas do. Ranking D.C. against the states is like ranking downtown Los Angeles by itself against all the other states—without the rest of California to balance it out.

Delaware has a minuscule population—less than a million—and its only urban center, Wilmington, has a lot of problems. This skews the rest of Delaware’s data, Albert argues.

“It’s not like there’s a tremendously high teen-pregnancy rate at Bethany Beach,” he said, naming a popular family summer resort town.

According to the National Campaign’s rough calculations, the Wilmington factor likely accounts for about a third of the explanation for the state’s high unplanned-pregnancy rate.

The reason for the other two thirds is anyone’s guess, but it likely has much to do with the cultural, transportation, and healthcare obstacles the Delawareans I interviewed have lived and seen. Those factors would likely be familiar to teens in any state.

Whatever it is, Albert said, "You can’t necessarily say they’re doing the nasty all the time down in Delaware.”

He’s joking, of course; there’s something funny about the idea that Delaware is engaged in a state-wide bacchanal. In that way, the state provides yet another valuable public-health lesson. Maybe Delaware, in its middle-of-the-road, stereotype-defying way, can help erode the stigma surrounding unplanned pregnancy—the notion that it only happens to women who are ignorant, libidinous, or reckless. In spite of its ranking on the unintended-pregnancy list, nothing about Delaware’s situation is exceptional. In other words, if it can happen to Delawarean women, it can happen to anyone. But it doesn’t have to.

( Top image via Monkey Business Images / Shutterstock.com )