Are Mobile Crime Alerts Making You Racist?

Pavel Ignatov/Shutterstock.com

Citizens want details on crime in their neighborhoods, and law enforcement agencies are giving it to them. But there is such a thing as too much information.

Ask me what my plans are on a given Saturday night, and you'll get a wide variety of answers (largely dependent on how enticing my DVR queue is looking). But I can tell you what my Sunday morning looks like, every time: I roll over in bed, grab my smartphone, and review one, two, three or more text messages from 893-61. This is not a spurned ex-boyfriend—it’s the number for AlertDC, the District of Columbia’s communications system that sends emergency alerts and notifications straight to my phone. The alerts are invariably telling me, in their peculiar 140-character patois, that something unfortunate happened in my neighborhood the night before.

When I signed up for AlertDC a few months ago, I had what I thought were the best of intentions. The alert system was revamped in August of last year, the exact anniversary of my move to my neighborhood. This seemed fortuitous. I should be more engaged, I thought. I should be more aware of what’s happening in my immediate community. Keeping tabs on nearby crimes and emergencies via text message seemed like a decent place to start.

But the messages came thick and fast. There are some days when I receive more text messages about crimes—stabbings, “robbery fear,” “robbery-F&V,” or robbery force and violence—than I do from friends. It was not long before the messages began, imperceptibly at first, to affect my day-to-day behavior. I probably shouldn’t go grocery shopping right now, even though I desperately need food—someone was mugged around this time a week ago.

The paranoia was bad enough, but then things took a far more insidious turn. Many—though certainly not all—of the crime alerts I receive specify the race of the alleged perpetrator. Some of these are nominally, and perhaps helpfully, specific: “Lookout for 2 B/M [black males], (1) black jacket, blue hood (2) black clothing, red/white shoes” reads an alert I received this month concerning a robbery that occurred just a few minutes up the road. That one maybe has enough detail to identify the suspects, should I have happened to spot them later that night. Most are less helpful: “Lookout for 4-5 B/Ms, 5’8-5’10”, (1) wearing a red hat.” This could be nearly any group of young black men walking in my neighborhood. Would avoiding B/Ms, particularly those in red hats, that day or week or month really decrease my chances of falling victim to the same crime? Logically, I know this is ridiculous at best, and racial profiling at worst.

And yet, I find myself increasingly skittish around the many, many men I encounter who fit the descriptions that come across my phone. According to local crime statistics, I have a middling to small chance of becoming a victim of crime in my neighborhood. But life with crime alerts had made me feel a bit like becoming a victim is only a matter of time.

A caveat here: To AlertDC and D.C. law enforcement’s credit, the service makes it pretty easy for me to customize my crime alert settings. I could unsubscribe from Police Alerts altogether, opting instead for only traffic or weather messages. Or I could receive just emails, not text messages, though these alerts go straight to my ever-present phone, too.

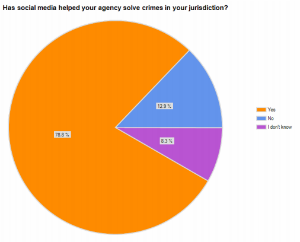

D.C. is far from alone in instituting the use of these personalized, straight-to-phone crime alerts. According to a 2014 International Association of Chiefs of Police survey [PDF], 95 percent of 600 responding law enforcement agencies use social media in some capacity to engage with residents. Nearly 80 percent use social media to notify the public of crime problems. Ninety-five percent use Facebook, 66 percent use Twitter, 36 percent use YouTube, and 24 percent use Nixle —a platform designed specifically to allow agencies to reach residents via text message and email.

It's a technology that has been grappled with much more explicitly on college campuses; while many municipal agencies have used email and mobile messaging to distribute alerts only in the past decade or so, the Clery Act has required schools to give their communities “timely warnings” of threats to public safety since 1989. In 2011, the University of Michigan’s Department of Public Safety released an alert on a possible shooting incident involving a “black male, possibly bald or with dread locks, wearing an orange, black or red t-shirt, with gray sweat pants.” A less helpful alert could hardly be conceived.

“My central concern … is that this description and the medium it was pipelined through — via e-mail — results in a unique practice of racial profiling that perpetually typecasts African-American men as pathological menaces to Ann Arbor’s society,” Michigan graduate student David Green subsequently wrote in an op-ed in the campus daily. He asked Michigan authorities to be “more conscious” in crafting crime alerts, a request that was echoed by a number of student groups on campus.

Detailed information on the horrible things that happen around us is increasingly at our fingertips. But in cities and communities where police feel growing pressure to keep residents informed of every incident, the question of how that information is best distributed is far from settled.

*****

There’s a big difference, explains Nixle’s Jim Gatta, between push and pull notifications. Pull notifications are like what you see on Facebook or Twitter: If your local police department shares details of an armed robbery on social media, that information passively exists in your feeds, where it stands a decent chance of getting buried among photos of your high school crush’s new baby, or updates from your cousin’s trip to Cancun.

Nixle’s updates are the other kind, push notifications, meaning they go straight to your phone, often via text message. “If something’s affecting me—if there’s an impending snowstorm coming down the road or someone escaped from the prison that’s two miles from my house—I want my phone to blow up,” says Gatta. “I want it to ding. I want to know minute by minute.”

That’s a pretty natural human feeling, and it’s one to which police departments have had to respond: 7,500 law enforcement agencies across the nation now use Nixle, a number that’s grown dramatically in just the last two years. “We get important messages in front of you that you need to look at,” Gatta says.

The "push" aspect of SMS crime alerts may be why I’m having such a visceral reaction to them, suggests Jack Glaser, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkley, who studies the social cognition of racial profiling. One of the reasons these alerts may have different effects than plain-old media reports is their “illusory, personal nature,” he says. “I think when people are watching TV or listening to the radio there’s the chronic feeling that this a shared experience. Even though you know rationally that you’re getting something like that on your phone, that it’s being broadcast widely … it feels like it’s for you.”

That kind of perceived personalization can have a particularly deleterious effect on recipients’ perceptions of race and crime, says Glaser. First, the well-established psychological phenomenon of “illusory correlation” demonstrates people exposed to two, unrelated things simultaneously often see correlations even when they don’t exist. “Crime [is] a rare event and racial minorities [are] an inherently rare event,” explains Glaser. “We tend to overestimate the correlation. When two rare events co-occur, it’s highly distinctive, and it will just stand out in [people’s] minds.” In other words: The more alleged minority-perpetrated crime we’re exposed to on a regular basis, the more likely we are to think that minorities commit crimes everywhere they go.

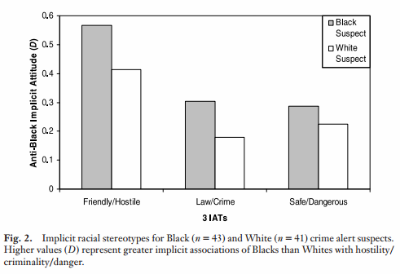

Second, a 2008 study [PDF] of community crime alerts by a team of Harvard psychologists suggests that crime alerts specifically affect recipients’ beliefs about race and crime, particularly when the notifications include details on people of color. The experiment asked 99 white and Asian participants to read one of two nearly-identical crime alerts on a violent robbery. The difference: one version of the crime alert described the suspect as “black,” the other as “white.” Those who received the black suspect alert were subsequently much more likely to associate blacks with hostility, criminality and danger than those who had received the white suspect scenario. The results, the researchers write, “illustrate how a single word, indicating the racial identity of an alleged crime suspect, can shift implicit and explicit stereotypes toward entire racial groups.”

*****

Of course, we run into a practical problem here: Should law enforcement agencies refrain from mentioning the race of a suspected criminal for fear of compounding racial bias? Certainly not. In many cases, race is just another helpful descriptor among many. But vague alarms—the unspecific “black but bald or with dread locks” ones—should raise our hackles. They’re not informative, which means they're failing at the basic task of allowing the public to avoid or assist in tracking down the bad guys. If I want to avoid an ambiguous shooting incident, whom should I steer clear of, exactly?

In South Brunswick, New Jersey, police department spokesman Lieutenant James Ryan says he does worry that Nixle’s text messaging and emailing capabilities provides a skewed perception of community crime. “Some people may look at all these Nixles and say, ‘Wow, look at all those burglaries.’ But then when you see our crime reports come out you think, ‘Hey, that’s not true.’” As a result, he says the South Brunswick department is particularly careful about only using Nixle to send alerts when getting the public involved might truly help in an investigation, or help them avoid becoming the next victim. “When we put out a crime alert, we put it in thinking, ‘Is it a pattern? Is it something the public is going to help us with?’ If it’s neither of those two things, then there’s no reason to put them out,” he says.

Still, Ryan says using the department’s direct-to-resident communication abilities does get results. In September 2014, the South Brunswick Police released an alert via Nixle that the police had video of an armed suspect attempting to rob a local restaurant. The alert included a specific description that pegged the man as a “a light skinned male possible Hispanic, 6’02”, bald or shaved head and a thin beard.” Several callers identified the suspect within hours of releasing the video, and he was eventually arrested .

These sorts of success stories notwithstanding, there's clearly a case to be made for increased awareness among law enforcement agencies and all those who interact with them that everything we do, see and read affects the way we view our world. As the Harvard psychologists wrote in their study: “If a brief reading of a momentary visualization of a fictional crime scenario or a text-only crime alert can measurably shift implicit attitudes, imagine the effect that a two-hour motion picture or a graphic news clip could have on the minds of an audience.” With mobile crime alerts—as with most technology—the pitfalls come not from the alerts themselves, but the people who craft and read them.

( Image via Pavel Ignatov / Shutterstock.com )

NEXT STORY: How Obama Has Left Red States Deeper in the Red