Blizzards and the Birth of the Modern Mayor

Library of Congress

Connecting state and local government leaders

The Great White Hurricane of 1888 demonstrated the vulnerability of urban life, and led voters to demand greater protection.

The modern American mayor was born in a blizzard. In 1888, the Great White Hurricane bore down on the metropolises of the eastern seaboard, destroying infrastructure and paralyzing commerce. The devastation it left behind convinced voters that America's burgeoning cities could function only if local governments assumed a larger, more proactive role.

The Blizzard of 1888 was a cataclysm. It claimed 400 lives, sank 200 ships, and paralyzed cities for days. It dumped an average of 30 to 40 inches of snow over southeastern New York and southern New England, but high winds whipped the fluffy flakes into towering piles. In Brooklyn, one snowdrift measured 52 feet tall.

Most residents were caught unprepared. Late 19th-century cities were monuments to man's mastery of nature. Elevated railroads whisked passengers about; streetlights banished the darkness of night; telephone and telegraph wires criss-crossed the roads; horses hauled hundreds of millions of riders around the street railroads; and delivery carts ferried coal, dry goods, and all conceivable comestibles about the streets.

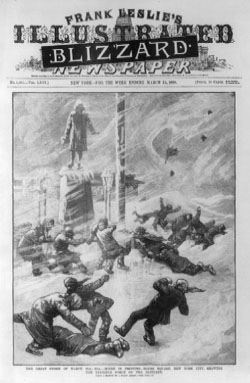

The modern metropolis seemed buffered against the perils of extreme weather. After a devastating blizzard early in the winter of 1888 struck the Great Plains,Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper sniffed about, "the folly of settling in a wild country, especially on bleak plains, however cheap the land may be, without assured means of providing decent shelter, fuel and provisions for more than the immediate future." Dense, urban neighborhoods might be more expensive, but supplies and aid were never distant.

When the storm struck, though, the technological conveniences and amenities of urban life were suddenly exposed as vulnerabilities. In eastern cities, almost all of the electric lights and most of the gas lamps went dark. Streetcars ground to a halt. Passengers hurtling from one city to the next were stranded on the rails, as trains stalled out in enormous snowdrifts. Poles snapped under the weight of the snow, weaving spiders' webs of crackling wires across the streets. With regular deliveries suspended, housewives husbanded their coal, mothers ran short of milk, and housebound residents scraped their larders bare. Funeral homes could not take bodies out of the city for burial, and so stacked them in barns and sheds.

"All of this was very trying to a people accustomed to the intense activity of metropolitan life," remarked the Independent, "and to the uninterrupted use of those wonderful contrivances by which man overcomes the natural barriers to instantaneous intercourse, and to the rapid and regular exchange of commodities." The Herald agreed. "The fine, widely extended machine we call a city," it observed, "...like other machines, is easily arrested."

Even Frank Leslie's seemed chastened:

If anything can be done in America, it can be done in New York; and New York has learned in less than a day, or ought to have learned, how poor and weak is man when brought face to face with the forces of Nature....It is well to think of these things and to abate somewhat of the pert self-satisfaction with which we recount the triumphs and inventions and wonderful applications of human science. Of what avail were all these against a fall of snow, the very type of evanescence?

The blizzard demonstrated the need for more robust urban infrastructure. Boston and New York, which had contemplated building subways before, nowraced to complete them. Cities also constructed new subterranean conduits, carrying electric, telephone and telegraph wires, an investment spurred by the blizzard. "What an argument it furnished for underground transit and underground wires!" exalted the Tribune. Congress soon authorized the Post Office to build networks of pneumatic tubes, shooting the mail around major cities, safely out of reach of the snow.

But grappling with the vulnerability of interconnected urban systems sometimes required not just larger investments, but hard choices. Before the blizzard, most cities dealt with storms by packing down the snow, making streets navigable by sled or sleigh. Streetcars, though, required clear tracks. Mayors chose maintaining mass transit over catering to the smaller, wealthier set that preferred sleigh rides. Shovels and plows replaced snow rollers.

The blizzard's legacy, though, extended beyond these physical monuments. It changed the way Americans viewed urban life. Cities had seemed to rise above nature, but their residents now understood that the very technologies that shielded them against the ordinary vicissitudes of nature simultaneously heightened their vulnerability to its extremes. They demanded more of public utilities, public infrastructure, and public servants.

Before 1888, most urban residents were content to hunker down and endure blizzards. Mayors might distribute patronage and cut ribbons, but few voters expected them to do much more. New York's Mayor Abram Hewitt rode out the storm in the comfort of his Lexington Avenue mansion. When he finally issued a public statement after four days, it was an ineffectual call for private property owners to help clear snow from their gutters.

The storm altered those expectations. Newly aware of their own vulnerability, city dwellers demanded that their mayors do more to protect them from nature's wrath. And mayors, in turn, have learned that their most basic responsibility is ensuring that services continue to function, no matter how extreme the weather. As storms bear down, they take to the airwaves to demonstrate their competence and resolve. "Our city has been through blizzards before," said Boston's Marty Walsh, "and I am confident we are prepared." In New York, Bill de Blasio urgedNew Yorkers to "to prepare for something worse than we have seen before."

Storms are now the yardsticks by which voters evaluate their mayors, judging their skill at operating the complicated machinery of municipal administration. When the flakes start falling, the test begins. And when it stops, voters emerge to measure the snowfall—and those charged with cleaning it up.