The Connection Between Successful Cities and Inequality

New York City’s Gini coefficient—the standard measure of income inequality—is now equal to Swaziland. Anthony Correia / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

New research shows that the largest U.S. cities would do well to focus on workers at the bottom of the economic ladder.

Thomas Piketty’s Capital helped make inequality a household word last year by arguing that it's a basic outcome of modern capitalism. “Thomas Piketty won 2014,” announced Slate, and the Upshot points out that inequality has been the theme du jour at the American Economic Association's annual meeting.

Indeed, inequality has become an increasingly dominant feature of U.S. cities. A recent U.S. Conference of Mayors report [PDF] shows that income inequality increased in over two-thirds of U.S. metropolitan areas between 2005 and 2012. The wage gap, meanwhile, nearly doubled from 12 percent to 23 percent in the decade between 2002 and 2012. New York City’s Gini coefficient—the standard measure of income inequality— is now equal to Swaziland’s, Chicago’s almost identical to El Salvador’s, and San Francisco looks like Madagascar.

A pair of new economic studies take on the rising challenge of urban inequality in new and important ways: one by Jung Hyun Choi and Richard K. Green , both of the University of Southern California, and the other [PDF] by Nathaniel Baum-Snow of Brown University, Matthew Freedman of Drexel University, and Ronni Pavan of Royal Holloway-University of London.

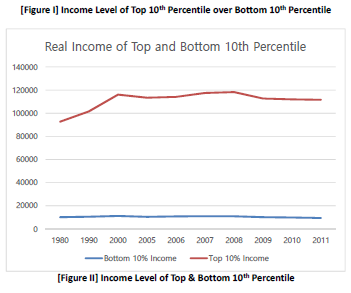

The first study, by Choi and Green, examines metro area-level inequality via the top and bottom 10th percentiles of U.S. income distribution between 1980 and 2011. This metric, an alternative to the more conventional Gini coefficient,enables them to determine whether inequality level changes are due to shifts in the top or bottom of the income distribution. The graph below, which constitutes the first part of their analysis, shows that while absolute changes in the level of income for the top 10th percentile have been relatively volatile in response to broader economic trends, the incomes of those in the bottom 10th percentile have been flat.

To get at why this has been the case, Choi and Green use regression analyses to examine the relationship between income inequality across all of the U.S.’s metropolitan areas and their key characteristics, including race, industry, skills, job market conditions, residential mobility and unionization.

Their results comport with my own findings, which I’ve written about on this site . They found that the level of income inequality is greater in metro areas with negative labor market conditions, better educated populations and greater industrial specialization—in other words, skills clustering. Between 1980 and 2000, Choi and Green also found that highly skilled labor was positively associated with changes in income inequality, though that relationship reversed between 2000 and 2011. During the pre-recession housing boom, Choi and Green’s results show that metros with greater numbers of Hispanic and Asian households had greater increases in income levels in the bottom 10th percentile, while the period after the bust saw real income drop in the bottom 10th percentile in areas with greater proportions of black households. Finally, the researchers found that unionization in metros is associated with reduced income inequality.

*****

The second study, by Baum-Snow et al., zooms in on larger cities to determine how a number of factors have affected increases in wage inequality between 1980 and 2007. Here, Baum-Snow and Pavan follow up earlier work that found that city size alone accounts for about 25 to 35 percent of the total increase in income inequality between 1979 and 2007, beating out the effects of skills, human capital and industry composition.

Using U.S. Census data, the study takes a detailed look at how the clustering of manufacturing capital and changes in the relative supply of skilled labor affect large-scale wage inequality. The researchers evaluate the relationships between these workers’ hourly wages and a number of variables, including age, sex, race, occupation, residential location, immigrant status and skill level.

What they found is that high-skill clustering is associated with higher returns and high wages for high-skilled workers—but rising tides don’t necessarily raise all boats. Instead, they find that wage gaps increase and there are fewer jobs for unskilled workers in larger cities. Indeed, their results suggest that city or metro size accounts for a whopping one-third of the increase in wage inequality nationally since 1980.

The culprit here, they indicate, is the very clustering that powers urban growth in the first place. As they write, “an important fraction of the nationwide increase in the skill premium since 1980 can … be traced back to increases in the skill bias of agglomeration economies.” Snow-Baum et al. note that the growing relationship between high-skill work and city size in the 1990s, a period of wage stability with respect to city size, is additional evidence of the importance of city size in creating and perpetuating clustered economies.

*****

The bottom line: inequality is not just an occasional bug of urban economies. It’s a fundamental feature of them, an elemental byproduct of the same basic clustering force that underpins metros’ rise as centers of innovation, startups and economic growth. In other words, the exact same phenomenon of skill clustering that has made tech hubs like San Francisco, New York, and Boston such successes has contributed to the rise of inequality, the growing gap between the haves and the have-nots.

This creates a huge conundrum for policymakers, who may be tempted by (deservedly) growing political clamor over rising inequality to throw the proverbial economic baby out with the bathwater by turning to measures that impede the clustering that generates economic growth in the first place. But it makes little sense to undermine growth and the revenues it brings to stave off inequality. Urban leaders would be much better off focusing on policies that boost the conditions of people at the bottom of the economic ladder, enhancing skills, upgrading low-end service jobs, and raising the minimum wage, as well as increasing the supply of housing, particularly affordable housing. The real key is to harness this new round of urban growth in ways that can create a more inclusive city.

(Image via Anthony Correia / Shutterstock.com )