Federal Grant Programs for States Are on the Chopping Block

House Speaker John Boehner of Ohio, joined by other House Republican leaders, speaks at a news conference on Capitol Hill earlier this month. J. Scott Applewhite / AP Photo

As the GOP begins budget reform, $640 billion in grants offer a tempting target.

WASHINGTON — With Republican majorities in both houses of Congress, one might expect a serious assault on federal spending and deficits, most likely focusing on domestic discretionary programs that prop up the budgets of state and local governments.

If it comes, the attack will be directed at budgets starting in federal fiscal year 2016, which begins next Oct. 1. Most of the budget for fiscal 2015 was settled in the so-called cromnibus legislation enacted in December.

Republican leaders in the House and Senate have pledged a return to “regular order” in budget deliberations, which would be a welcome departure from recent years’ reliance on belated omnibus funding bills, huge and incomprehensible as they are. Regular order would entail adoption of a budget resolution this spring, followed by passage of the 13 functional appropriations bills that have become endangered species in the omnibus jungle.

No specific course of action has yet been unveiled by Republican leaders in Congress. But a longtime tenet of GOP philosophy has been that government is spending and borrowing to excess. Republicans have focused mainly on domestic spending. Some have advocated cuts in entitlement programs such as food stamps, while others have voiced concern about the growth of grant programs now numbering more than 1,100—each with conditions imposed on recipients at the state and local levels.

Grant programs are increasingly in the spotlight. Federal spending data newly gathered and dissected by two nonprofits have served to emphasize how heavily states and localities have come to depend on federal subventions. And Republican intellectuals have been building a case against the grant programs, characterizing them as poisoned carrots, distorting local priorities while imposing one-size-fits-all matching and regulatory conditions.

At the same time, state, county and municipal budgets haven’t fully recovered from the Great Recession, so mayors, governors and other local officials are scrambling to fill the gaps. As oil prices drop, energy-dependent states like Texas, Alaska, New Mexico and Louisiana are suffering particular pain, but others states like Maryland and Virginia are also facing deficits close to or exceeding $1 billion in their upcoming fiscal years.

This week, the National Association of Counties declared that economic recovery has been anemic in many counties, and expressed the fear that federal policies, including appropriations cuts, might worsen the situation.

So the philosophical confronts the practical: To what extent can congressional Republicans pursue their anti-spending drive when it threatens the fiscal stability of the states, 28 of which are now run by GOP governors.

Dependency Data

The explosive growth of federal grant programs has been tracked over the years in Table 12.2 of the Historical Tables of the U.S. Government Budget, and also by the Government Accountability Office.

The Budget Historical Tables document actually looks not only backward but also forward based on current trends, and a year ago it estimated that grants to state and local governments would total $640.8 billion in the 2015 fiscal year, in the following categories:

The complexities and interdependencies of many of these grant programs is legendary—enough to prompt GAO to issue a long report detailing their duplication and overlap.

But the reports from the U.S. Office of Management and Budget and GAO do not offer the level of detail on federal spending in the states that once was the province of the U.S. Census Bureau, which until 2012 published its annual Consolidated Federal Funds Report detailing spending in the states.

Nor does USASpending.gov, managed by the U.S. General Services Administration, offer a comprehensive accounting of spending in the states. The website was recently found to have omitted more than $600 billion in grants and awards, and its current version captures only $134.7 billion in grants for 2015, according to The Washington Post.

Two think tanks have stepped into the data breach: The National Priorities Project with a website called State Smart and the the Pew Charitable Trusts with its Fiscal Federalism Initiative.

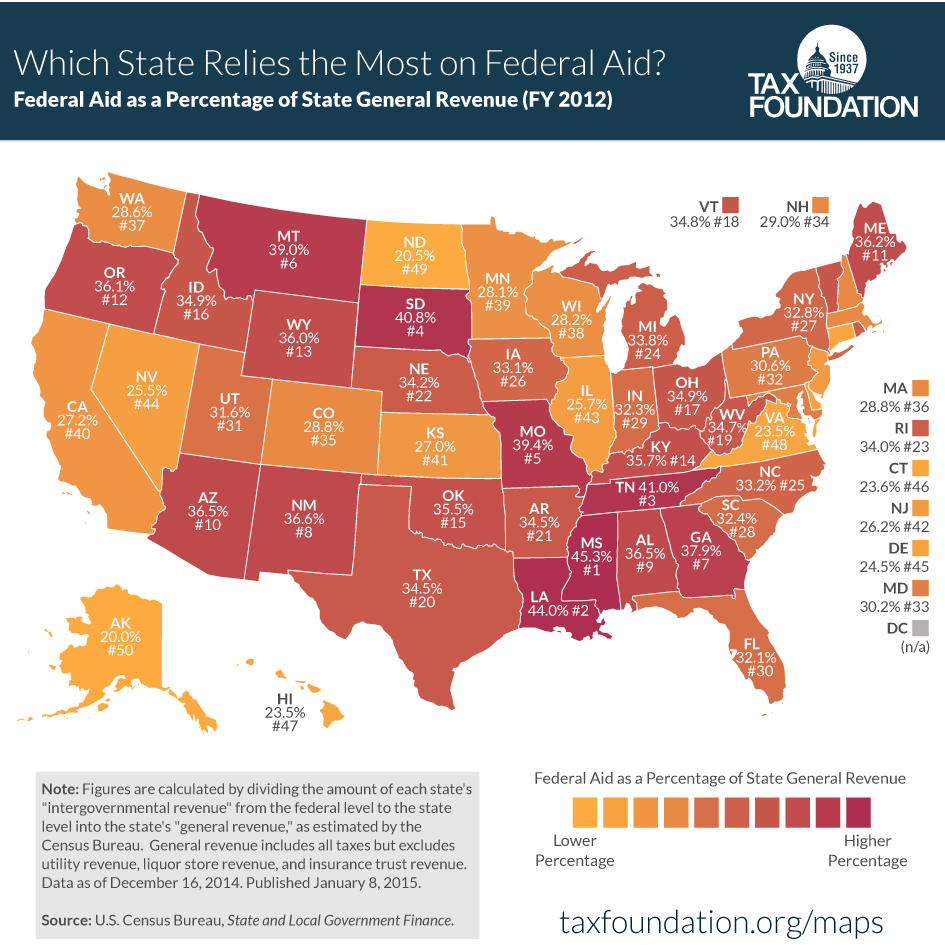

In admirable detail, these sites illuminate the dependency of the states on subventions from Uncle Sam. State Smart calculates that federal grants comprised 32 percent of state government revenues in 2012. In early January, the Tax Foundation joined the parade, with maps also detailing states' reliance on federal funding.

According to State Smart data, In Maine, the share was 36.5 percent, or $3 billion, to fund Medicaid, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, Community Development Block Grants and other programs.

Maine’s state budget is more dependent on federal grants than most other states. The Pine Tree State is outranked only by Mississippi (at the top with 45.4 percent), Louisiana, Missouri, South Dakota, Montana and Arizona. Least dependent are North Dakota, Virginia and Connecticut, each with less than 25 percent of revenues coming from Uncle Sam.

An interactive map, one of many on these sites, allows citizens to see the sources of state government revenue. Other maps show such data as the flow of federal funds into every state from programs directly compensating individual residents (where Florida ranks first). Pew’s site allows state and county-specific searches showing flows of federal funds of in a wide variety of programs.

To Have or Have Not

Grant programs can be viewed as bribery: Uncle Sam offering dough to induce state and local governments to undertake activities they might otherwise eschew. The programs can also be seen as a form of coercion: Uncle Sam makes money available to states, and those who don’t take it end up subsidizing, through their citizens’ federal tax payments, those who do.

Medicaid offers a leading example of the principles in play. In 2012, the Supreme Court, ruling in National Federation of Independent Business et al v. Sebelius, declared that states did not have to accept the substantial enlargement of the Medicaid program mandated by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Many Republican governors have turned the expansion down; at last count, 22 states had not yet embraced it.

Medicaid has long claimed large shares of state budgets, so governors and legislators may be wary of promises that Uncle Sam will cover 93 percent of the expansion's cost through 2022.

At the same time those who refuse are leaving a lot of money on the table. The drama has been playing out in Virginia, where Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a Democrat, is preparing to ask the legislature again for authority to expand.

By covering those with higher incomes than under the existing program, the expansion would extend coverage to 400,000 Virginians who now have little or no insurance. McAuliffe’s ambition is not given much of a chance in the Republican-controlled legislature, even though the expansion would bring $1.8 billion per year in federal funding to the state, or nearly $15 billion over the next eight years.

The Texas State Capitol in Austin (Photo by f11photo / Shutterstock.com)

Texas has also avoided the Medicaid expansion. But plummeting energy prices have crimped the Lone Star State’s budget at a time when there’s much demand for infrastructure and education improvements.

As The El Paso Times reported on Jan. 3, the budget squeeze may induce reluctant Republican legislators to find a way to adopt the expansion, which would bring a tidy $100 billion to the state by 2022.

The Texas situation illustrates the tensions between embracing the welfare state and standing on conservative principle. Explosive growth of the food stamps program offers another example.

While conservatives in Congress have been anxious to cut back on the program—and the U.S. House last year passed a major reduction—officials in Republican-led states like Florida have hired people to enroll eligible citizens in what’s now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in the knowledge that this will boost incomes in their jurisdictions. SNAP, an entitlement program, has become a major budget item, spending some $70 billion in 2014.

And new grant programs are always on the horizon. High-speed rail improvements and Race to the Top education programs, for example, were created as part of the federal stimulus program. Only some states participated, and Race to the Top has now been ended.

Just last week, President Obama said his fiscal 2016 budget would unveil a brand new program of subsidies designed to cut the cost of attending community college to zero.

The Conservative Case

An op-ed column by conservative commentator George Will, published Dec. 8, drew attention to a new book by former New York Sen. James L. Buckley that offers the most comprehensive critique of the federal grants-in-aid “cornucopia” yet published.

Buckley’s book is titled “Saving Congress From Itself,” but its subtitle more precisely captures its thesis: “Emancipating the States and Empowering Their People.”

The book is replete with examples of distortions occasioned by federal programs. One that raised Buckley’s hackles was a $430,000 grant to a nearby school district to widen sidewalks—the money flowing from a $180 million-a-year Safe Routes to School program, whose aim is to fight obesity by encouraging kids to walk or bike to school.

Buckley writes:

The problem today is that those governing our towns and states are no longer in control of a large proportion of the government activities that affect our lives. In too many respects, our state officials now serve as administrators of programs designed in Washington by civil servants who are beyond our reach, immune to the discipline of the ballot box, and the least informed about our particular conditions and needs.

Even in a post-earmarks world, as Buckley notes, members of Congress spend a lot of their time making sure their districts are adequately served by the hundreds of grant programs. Organizations like the National Governors Association and the National Conference of Mayors exist to lobby the feds for more money—and less regulation—and more than 400 cities have seen fit to hire their own lobbyists at a very considerable cost. And, of course, many recipients see the federal largesse as “free money” they would be leaving on the table if they didn’t apply.’

Richard A. Epstein, professor of law at New York University, and Mario Loyola, a senior fellow at the Texas Public Policy Foundation teamed up last year to write a scathing attack on what they termed the “relentless expansion of federal power.”

In a July 31 treatise published by The Atlantic, Epstein and Loyola write:

Programs like Medicaid, Common Core, the Clean Air Act and the federal highway system enjoy popular support because they appear to allow the federal government to accomplish things all Americans want, at least in the short run. But those programs often turn states into mere field offices of the federal government, often against their will, in turn creating a host of structural problems.

They observe that states that might establish their own health programs for the needy would be giving up Medicaid funding that their citizens had, through their taxes, already paid for, in effect paying twice to provide the same services. The Common Core educational standards, initially developed by the governors’ association, was in effect made a condition of receiving education grants by the Obama administration. States lose highway funds if they drop their legal drinking age below 21. These and other examples they characterize as a pressing “separation-of-powers issue” urgently in need of correction.

Action This Year

Obama’s proposal to make community college free to serious students would cost federal taxpayers $60 billion over 10 years, according to administration estimates. Participating states would be required to put up a quarter of overall costs, probably another $20 billion. The GOP-controlled Congress may find this a relatively painless means of saying no to further expansion of the huge federal grants cornucopia.

But conservatives will find cutting back on existing grant programs, each serving entrenched interests, a considerably heavier lift. Their successes and failures in shaving federal spending will play out in budget and appropriations action that will soon get underway.

Timothy B. Clark is editor at large at Government Executive.