The Sorry State of 'Good Samaritan' Laws

The Parable of the Good Samaritan by Jan Wijnants. Wikimedia Commons

Whether you can safely help a stranger during a crisis largely depends on where you live.

A priest, a Levite, and a Samaritan walk down a road

in the Bible

. On the road is a man, who has been robbed, beaten, and left for dead.

You probably know the rest: The priest thinks, "If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?" The Levite, same thing. The Samaritan thinks, "If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?"

We generally laud “good Samaritans,” people who stop to aid someone in distress. But should you find yourself in such a situation while walking down a street today in Ann Arbor or Detroit, you, too, might hesitate:

Michigan law protects

medical personnel, “block parent volunteers,” and members of the National Ski Patrol from potential lawsuits related to any “emergency care” they render—but not anyone else. There are exceptions, however, if you're specifically

giving CPR or using an emergency defibrillator

. Got all that?

So what is a good person to do when she comes upon, say, the scene of an auto accident where a victim must be moved to avoid further injury or death? There are two answers: 1) Step in and hope you don’t cause further injury—but risk getting sued if you do or the victim dies despite your efforts. 2) Google the laws of wherever you are and consider the possible legal ramifications of helping.

The latter choice doesn't put you in great Biblical company. But to be fair, the original good Samaritan was operating in far less litigious times. He was not a doctor who could lose his license by helping in the wrong place or manner. And there was no 911 to call to summon more qualified people for the job.

So-called “good Samaritan laws” are meant to extend protection from lawsuits or prosecution to an everyday person who steps in to help a stranger—barring totally negligent behavior. There are good Samaritan laws in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia and in many other countries and cities throughout the world. Not all of them are so good.

China’s laws came under scrutiny in 2011 following the death of toddler Wang Yue , who was run over by two vehicles in Foshong, in the province of Guangdong, while nearly 20 bystanders did nothing. The speculation at the time was that the witnesses may have been influenced by a heavily publicized 2006 case , where a Nanjing man was sued by an elderly woman he had helped after she broke her hip. (She won, and he was forced to pay her $6,000.) After worldwide outcry surrounding Wang Yue's death, China passed its first good Samaritan law in 2013 in Shenzhen, a major city in Guangdong province.

In

Finland

and

Germany

, failing to assist is actually punishable by law, and those providing aid are protected to varying degrees.

Israeli

law requires bystanders to help, and good Samaritans may even be compensated.

But in the U.S.,

laws vary wildly among states

, and not all completely protect a layperson jumping into a crisis. Some, such as those in Minnesota and Vermont, compel bystanders to render aid. Others, such as those in Michigan, protect bystanders who specifically do

not

help. For off-duty medical personnel responding, things get

murkier

still: Twenty-four states protect off-duty physicians giving emergency care within a hospital. Six don’t. And two others have a “duty to assist” law for physicians.

There can be a tricky legal distinction, too, between providing “emergency care” and providing “medical care.” This became clear to Lisa Torti in 2004, when she pulled friend Alexandra Van Horn from their wrecked car in Topanga, California. Van Horn was left without the use of her legs and brought a civil suit against Torti. California’s good Samaritan law, passed in 1980, stated then that "no person who in good faith, and not for compensation, renders emergency care at the scene of an emergency shall be liable for any civil damages resulting from any act or omission." That’s standard boilerplate language for such laws—except that two California courts interpreted “emergency care” as “medical care,” which only medical personnel were able to provide with legal protection. The statute has since been revised to cover “emergency medical or nonmedical care at the scene of an emergency,” and to stress that “[i]t is the intent of the Legislature to encourage other individuals to volunteer … to assist others in need during an emergency… ,” a change made in part because of Torti’s case.

By California’s old definition, “emegency care” did not cover rescue , such as moving them from danger. Michigan's current law also uses “emergency care” language, making its already confusing guidelines on what aid can safely be provided and by whom even muddier.

Where some places have expanded their good Samaritan laws, the additions may be very narrow, spurred by specific events (such as in Guangdong) or available new technology. The portion of Michagan’s law that protects citizens using emergency defibrillators, for instance, was added after a man died at a gym in former state Senator Gilda Jacobs' district and she considered her own potential liability in such a case had she been on the scene.

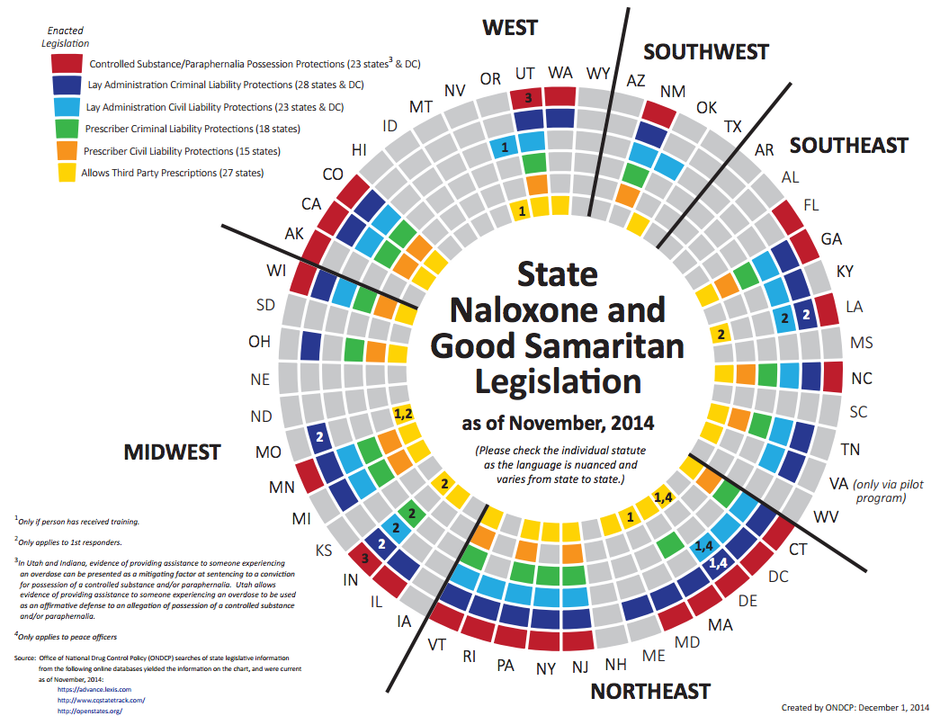

Over the past few years, some states have expanded their good Samaritan laws to include the administration of Naloxone, or Narcan, a drug that can reverse opiate overdoses. It is now available in a "pen" injection delivery system as well as a nasal spray that can be used without any medical training, and gained national attention when New York City police began carrying it as part of emergency kits.

In December, the Office of National Drug Control Policy released an updated list of states with good Samaritan laws on Naloxone and who exactly is protected. And this month, the Drug Policy Alliance released its most recent report on states with such laws, with careful distinctions about who is protected, where, and under what circumstances. A person calling 911 to report an overdose is protected from prosecution for related crimes in just 21 states, and a layperson can lawfully administer Naloxone in only 24 states plus D.C. (in four states, only emergency personnel or police may do so). So even if you do have access to Naloxone, it can be hard to know what your rights are in an O.D. emergency.

So the onus remains on the individual to research laws in their own cities and states, then make an educated decision on whether to help in an emergency. But it's also up to the individual to decide in the moment what it means to be a fellow human.