America's Infrastructure Crisis Is Really a Maintenance Crisis

A driver runs over a porthole in Portland in December. Don Ryan/AP

Here's what states can do about it.

It's long been time to focus more on maintaining America's existing roads and less on building new ones. The National Highway System already connects virtually all of the areas worth connecting. Driving peaked circa 2004 —and even earlier in some states . Traffic remains bad in many metros, but by itself expanding road networks can only temporarily alleviate the problem , and over time might even increase it.

And yet we build. We build without seeming to appreciate that every mile of fresh new road will one day become a mile of crumbling old road that needs additional attention. We build even though our pot of road funding requires increasingly creative (and arguably illegal ) solutions to stay anything other than empty.

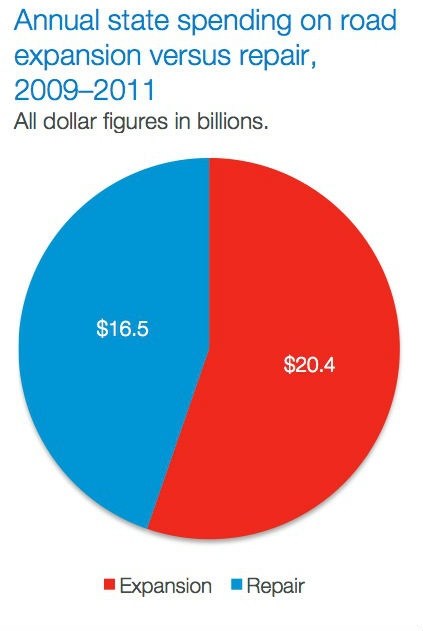

The numbers tell the story best. From 2004 to 2008, states dedicated just 43 percent of their road budgets to maintain existing roads despite the fact that they made up nearly 99 percent of the road system. The other 1 percent—new construction—got more than half the money. From 2009 to 2011 states did only marginally better, spending 55 percent of their road money ($20.4 billion) on expansion and just 45 percent on maintenance ($16.5 billion):

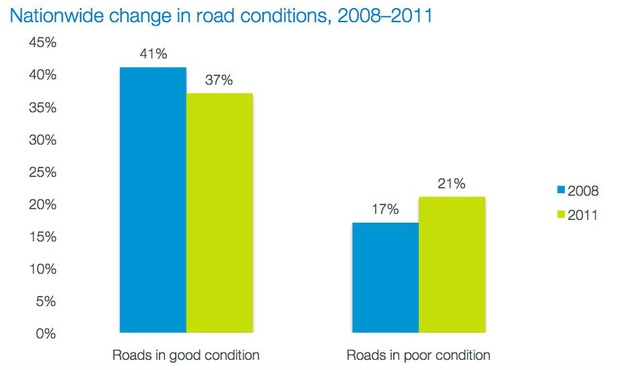

Predictably, over that same period, the country's roads got worse:

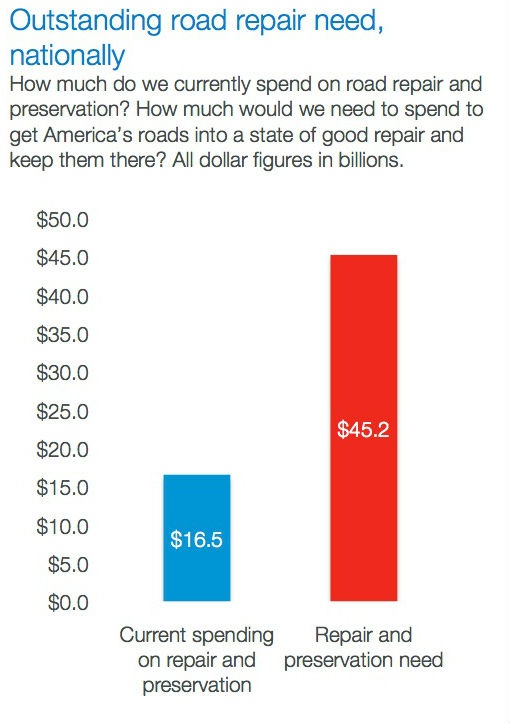

To keep the nation's roads in good repair would require about $45.2 billion a year, rather than the $16.5 currently spent on maintenance:

In other words, we need to use all the available road money each year to fix our roads, and then some, to prevent them from falling into a state of disrepair that endangers public safety. And the more roads we build, the more we need to one day fix.

Some States Do Better Than Others

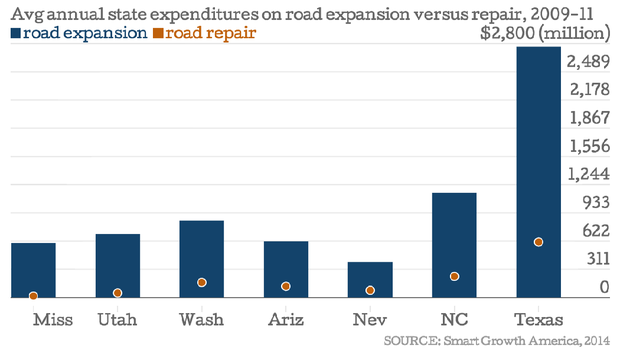

The above charts come from a 2014 Smart Growth America report spotted by Streetsblog's Angie Schmitt in a thoughtful recent post on America's maintenance crisis. On average the situation is bleak. Though some states do better than others, some do much, much worse.

Washington state, for instance, spent 84 percent of its road funding on expansion between 2009 and 2011. Over that same time period the condition of its existing roads unsurprisingly fell. The share of its roads in poor condition went from 12 percent in 2008 to 27 percent in 2011.

And Washington isn't the worst offender. According to the Smart Growth report, Mississippi spent 97 percent of its money on expansion. Utah wasn't far behind at 93 percent. Arizona, Nevada, North Carolina (all 83 percent), and Texas (82 percent) were in a similar ballpark.

Over that same period, road quality in each of these states declined in one form or another. The share of roads in poor condition in Mississippi rose from 18 to 30 percent, and in Utah from 7 to 11 percent, and in Arizona and North Carolina by a couple points each. Nevada's share of poor roads actually fell—but so did its share of road in "good" condition, from 62 percent all the way down to 24 percent.

Compare these numbers to those for states that spend as much in road repair as they should. In 2011, California spent $1.44 billion to maintain roads, against a need of $1.3 billion—a habit that seems to pay off in road quality. California improved its share of "good" roads from 2008 to 2011, and decreased its share of "poor" ones. New Jersey followed a similar course: spending $1.1 billion in repairs against $225 million in needs, while watching road quality improve.

That's not to say places like California or New Jersey don't have infrastructure problems. They do. But, at least circa 2011, they'd also recognized that maintenance counts as infrastructure, too.

What To Do About It

The most logical plan to address the problem—one we've pointed out before , and Brad Plumer at Vox raises again this week —is the "Fix It First" approach outlined in 2011 by transport scholars David Levinson and Matthew Kahn. Under this philosophy federal highway money would be directed away from new construction and used instead to "repair, maintain, rehabilitate, reconstruct, and enhance existing roads and bridges."

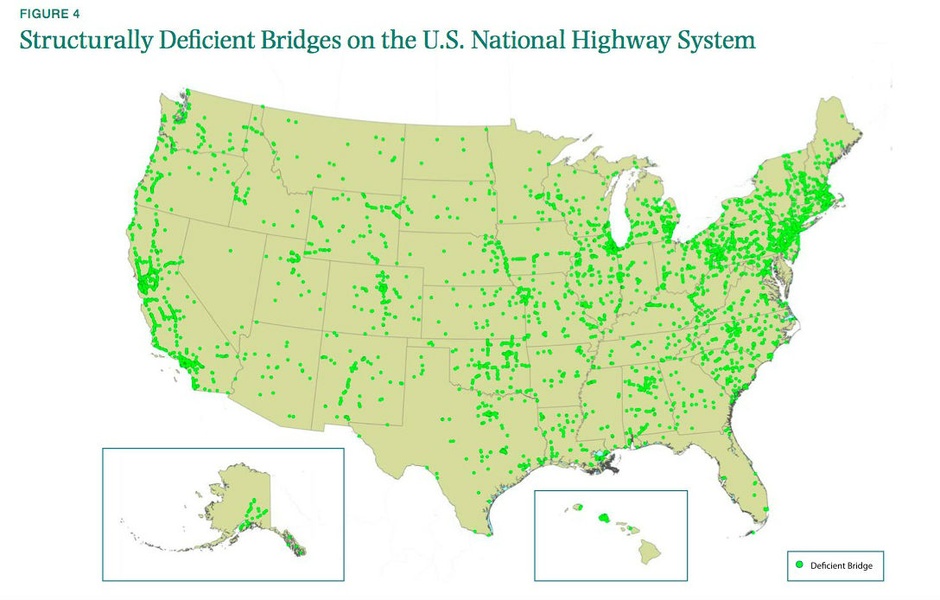

There are loads of reasons to like this plan. The sooner repairs are made, the cheaper they are: every $1 in preventive maintenance saves between $4 and $10 in future repairs, according to Levinson and Kahn. The funding system could be weighted by road condition to favor those in the worst shape (below, a map of structurally deficient U.S. bridges). On the whole, preserving a road is "less-risky" than building a new one, because the demand for its use is far more certain.

Another great thing about this plan is that by making it harder to expand roads, metro areas gain an incentive to charge drivers for congestion. As we've pointed out before, Americans don't pay nearly enough in gas taxes to offset the social costs of driving —of which time lost to traffic is a biggie. As driving became more expensive over time, local agencies could meet additional mobility demands with new investments in public transportation.

Speaking of transit, prioritizing maintenance is just as important here, too. The recent deadly electrical malfunction on the D.C. Metrorail system seems to have stemmed, at least in part, from infrastructure in need or repair or replacement . Delayed maintenance also played a role in recent incidents on the Metro-North commuter railroad outside New York City.

Writing recently at the Transportationist , Columbia planning scholar David King suggested that local government should have to meet certain criteria before receiving money for new transit projects. These include promoting smarter development, limiting parking, and dedicating street space to car alternatives. Agencies should also recover a minimum threshold of transit costs through fares—ensuring that they have enough money to run and maintain an existing system before lobbying to build a shiny new one:

If cities do the hard political work they should be rewarded. If all they do is raise taxes based on specious claims, they should be held accountable. We currently have this backwards.

Tyranny of the Ribbon

The hard political work begins with the tyranny of the ribbon. Of the many reasons infrastructure repairs get snubbed for construction, big public ribbon-cutting ceremonies that come with fresh projects—but not with stale maintenance—is near the top of the list. By the nature of their limited tenure and uncertain futures, politicians care more about attaching their name to a new project than extending the life of someone else's old one.

Smart Growth America suggests we "raise the profile of repair and preservation projects." That's easier said than done, and when done wrong the results can be disastrous. Take that time, in 2005 , when then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger tried to call public attention to road maintenance— by having a crew dig a pothole only to fill it :

In general, public ceremonies for maintenance just end up drawing little attention. During my recent conversation with MARTA chief Keith Parker , he said the Atlanta transit system had a tunnel ventilation project underway that may cost upwards of $200 million, and a radio system upgrade that will cost up to $50 million, and of course regular track enhancements and repairs—investments that, while necessary, will prevent the agency from doing what Parker called "sexier" expansion projects.

"When we tell people, 'hey, come out because we're going to have a celebration for the Clayton County expansion,' we expect a long line of people," he said. "When we say, 'hey look, we want to celebrate the tunnel ventilation project,' I don't think we'll get so many."

The media isn't blameless here. Just as politicians are loath to cut ribbons for infrastructure repairs, news organizations and bloggers prefer to hype new and shinier projects in the pipeline—or to wait until deferred maintenance causes a high-profile tragedy. There's no single or simple way to reverse America's growing infrastructure crisis, but reframing it as a maintenance crisis is a good place to start.