Do Chief Innovation Officers Deliver for Cities and States?

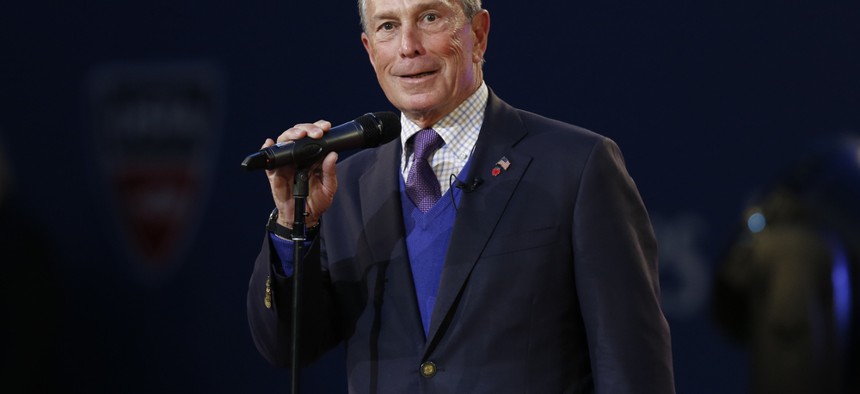

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg is investing millions in selected cities to allow them to hire innovation teams, or “i-teams.” lev radin / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

In addition to seeking breakthrough solutions to state and municipal government problems, they serve as catalysts in trying to transform operations.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

When then-Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley was wooing former tech entrepreneur Bryan Sivak to become his state’s new ideas guy, he asked what title Sivak thought he should have.

“Chief innovation officer,” suggested Sivak, who had just finished a stint as the District of Columbia’s chief technology officer. Initially O’Malley balked, Sivak said, because it “sounded kind of flaky.” But O’Malley, a Democrat and disciple of data-driven management, soon relented, and in 2011 Sivak became the first chief innovation officer of any state and possibly any U.S. city.

Since then, having a chief innovation officer in government has become all the rage. Colorado and Massachusetts now have somebody who holds that title, as do more than two dozen cities, from Philadelphia to Kansas City, Missouri, to Riverside, California. The increasing availability of digital data that government can use to analyze problems and assess solutions has accelerated the trend.

Tech firms were the first to anoint chief innovation officers to assess markets and identify new products and revenue. Corporations mimicked them, and now government has them to tackle everything from homelessness to violent crime, potholes to economic development.

In addition to seeking breakthrough solutions to civic problems, innovation officers serve as catalysts in trying to transform how government operates, especially in times of tight tax and budget constraints.

“You need to look across the board and figure out how to do things better, faster and tie it into the overall management structure,” said Sivak, now the chief technology officer and entrepreneur in residence at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

But some question whether innovation officers can bring original problem-solving to hidebound bureaucracies. Even Sivak acknowledges that “it’s a title that is very vague … and without a chief executive who understands it and looks at it as somebody we need to have, there’s a risk of it not being a very valuable position.”

Stephen Goldsmith, former mayor of Indianapolis and director of the Innovations in Government program at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, is harsher.

“Everybody is talking about innovation,” Goldsmith said. “A lot of what people are talking about in innovation is not that innovative.”

Sometimes, Goldsmith said, cities or states develop a mobile application for a government service and call it “innovation,” when they really haven’t revolutionized how government operates or devised better, thriftier and longer-term solutions for citizens and taxpayers.

CINOs vs. CIOs

In most states, chief information officers (CIOs) who oversee information technology operations essentially act as chief innovation officers (CINOs), said Doug Robinson, executive director of the National Association of State Chief Information Officers (NASCIO).

In a NASCIO survey of state CIOs in September, two-thirds said sparking innovation in how government operates was a critical part of their jobs, and 80 percent said they saw themselves as taking the lead in using data to address problems.

But Goldsmith said combining CIO and CINO roles isn’t a good idea. Although data is key to formulating new strategies and creating solutions, he said, it’s only a tool to assess what works or doesn’t work, and to measure the costs and productivity of a new approach.

What innovation officers really need, Goldsmith said, is the imprimatur of the governor or mayor to challenge the status quo up and down the bureaucratic ranks–even if it means stepping on some toes.

“You need someone in the executive office – the governor or the mayor – to take on entrenched interests: the bureaucracy, the vendors, or labor, and chart a path to a better solution,” Goldsmith said.

Tapping someone from outside government often works best. Some states and cities have created “entrepreneurs in residence” programs to attract successful people from the private sector willing to devote their time and creative juices to public service.

Like Sivak, many innovation officers and entrepreneurs in residence come from successful information technology startups that aren’t bound by the confines of government or large corporations.

“A lot of innovation in the private sector is from disruptive startups, with no ties to any corporate culture,” said Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a think tank that promotes technological innovation and productivity in Washington, D.C., and the states. Just like governments, he said, “many corporations are innovation-averse.”

Bloomberg’s Innovation Teams

Many cities and states don’t have the capability or money to come up with different solutions. Even when government employees have good ideas, they often are burdened with pressing daily workloads or trapped within bureaucracies.

Recognizing that, Bloomberg Philanthropies, a foundation started by the billionaire and former mayor of New York City Michael Bloomberg, is investing millions in selected cities to allow them to hire innovation teams, or “i-teams.” These squads of consultants join city government for three years to take on specific problems.

With $24 million divided among them in 2011, Atlanta reduced homelessness, Chicago overhauled its licensing of local businesses, Louisville cut the time it takes to rezone property, Memphis tackled gun violence and underprivileged neighborhoods and New Orleans reduced its murder rate.

After seeing those results, Bloomberg Philanthropies in December announced that it would donate between $400,000 and $1 million per year for three years to 12 other cities (Albuquerque; Boston; Centennial, Colorado; Jersey City, New Jersey; Los Angeles; Long Beach, California; Mobile, Alabama; Minneapolis; Peoria, Illinois; Rochester, New York; Syracuse, New York; and Seattle) to tackle issues such as affordable housing, public safety, infrastructure finance, customer service and job growth.

“Successful innovation depends as much on the ability to generate ideas as it does the capacity to execute them – and i-teams help cities do both,” Bloomberg said when the philanthropy announced the latest round of recipients.

Problem-Solving in Louisville

If there’s any government that can serve as a model for making innovation a part of its culture, Goldsmith said, it’s Louisville-Jefferson County, Kentucky.

There, Democratic Mayor Greg Fischer has the equivalent of a chief innovation officer and strategic planner in Ted Smith and the equivalent of a CIO, human resources chief and performance watchdog in Theresa Reno-Weber.

It’s Smith’s job in the mayor’s office to strategize, seek possible solutions and enlist outside help, such as businesses or nonprofits, to tackle issues. Reno-Weber’s job is to round up the data, harness government employees to achieve goals and then measure how well government is doing in meeting them.

Smith, for instance, will look at how to delay closing the city’s landfill, which is 30 years from becoming filled, and seek to get big institutions, such as hospitals, to help pay for recycling. Reno-Weber will assess how well that works and post data results on the city’s open portal, LouiStat, so the public can monitor them. The public can track all of Fischer’s initiatives on the site.

One task Smith and Reno-Weber are working on is reducing nonemergency calls to the 911 dispatch center. “It’s not only expensive,” Smith said of nonemergency ambulance runs, “but it means an ambulance may not be available to a heart-attack victim.”

The city now posts nurses in the 911 dispatch room to determine whether callers really need an ambulance or just a ride to the drug store, the grocery store, or the doctor’s office. If a situation isn’t life-threatening, an alternative response vehicle can be dispatched.

Meanwhile, Smith is assessing Reno-Weber’s data on nonemergency calls to see whether there’s a market for a private-sector transportation service to drive people who call 911 for nonemergency transportation.

So far, the city has cut its nonemergency call rate by 30 percent since 2012. The goal is to cut it in half by 2017.

Can other cities, and states, achieve similar outcomes by adopting a formal innovative approach to problem-solving? Sure, Smith said. In his opinion, “all … should have an innovation capacity.”

(Top photo by lev radin / Shutterstock.com; second photo, of Louisville, by American Spirit / Shutterstock.com)

NEXT STORY: When Useful Information Becomes Overwhelming