Exploring California's 12,000 Parks With Open Data

CaliParks.org

A just-launched app uses Instagram and Twitter to show younger users that their friends are already out at state parks, having a blast.

California’s extensive state park system is a guarantee that all the state’s citizens, not just the moneyed elite, will have access in perpetuity to the state’s embarrassment of natural riches—mountains, beaches, deserts, forests, you name it.

In recent years, however, the system has been damaged by financial woes and scandals. First, budget shortfalls threatened to shut down 70 of the 278 parks in the system, and led to cutbacks in hours and services at others. Then, after nonprofits and private groups raised money to save individual parks, it turned out the parks system’s administrators had been sitting on more than $50 million in unspent funds —a scandal that led to the resignation of the state’s parks director and the creation of the Parks Forward Commission . That group, charged with figuring out how to stabilize and modernize the system and its administration, has just released its recommendations .

Fundamental to all the recommendations is the idea that California’s parks should be courting and accommodating a younger, more diverse constituency, one that looks more like California itself. "Unless we get young people and their families using the parks now, the kind of political support that's needed won't be there," commission member Manuel Pastor told the Los Angeles Times .

One step toward that goal was launched last week: CaliParks , a web-based app designed to encourage exploration of and interaction with the entire state park system, as well as California’s national, regional and urban parks—a total of nearly 12,000 green spaces large and small, urban and wild.

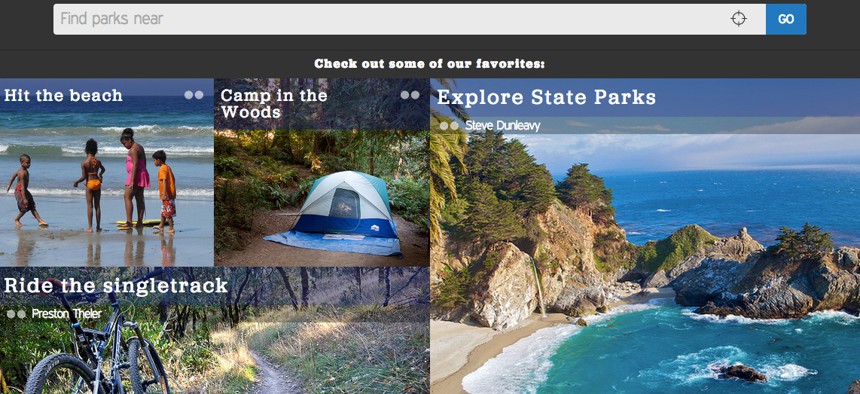

The new web-based app pulls in images from Instagram and Flickr to show users the variety of people using California's state parks. (CaliParks.org)

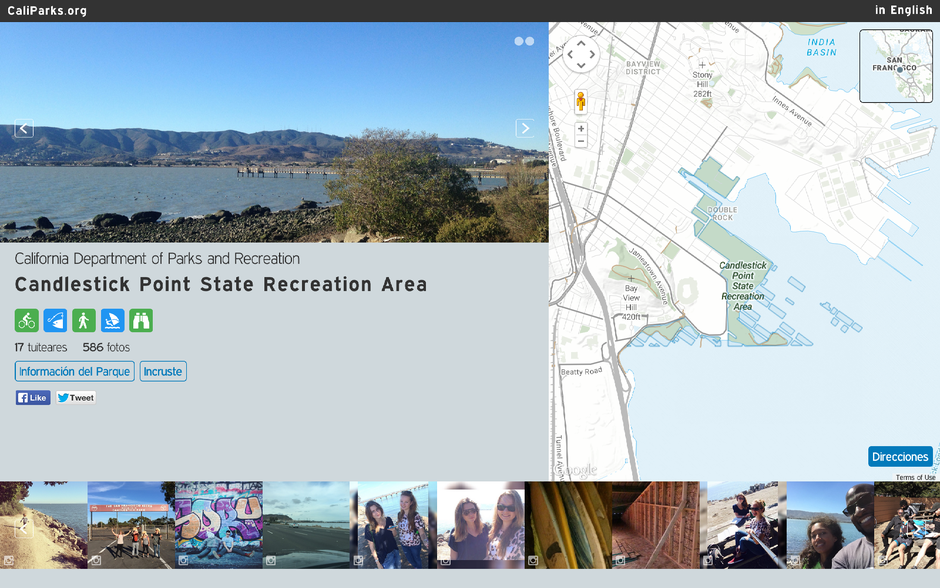

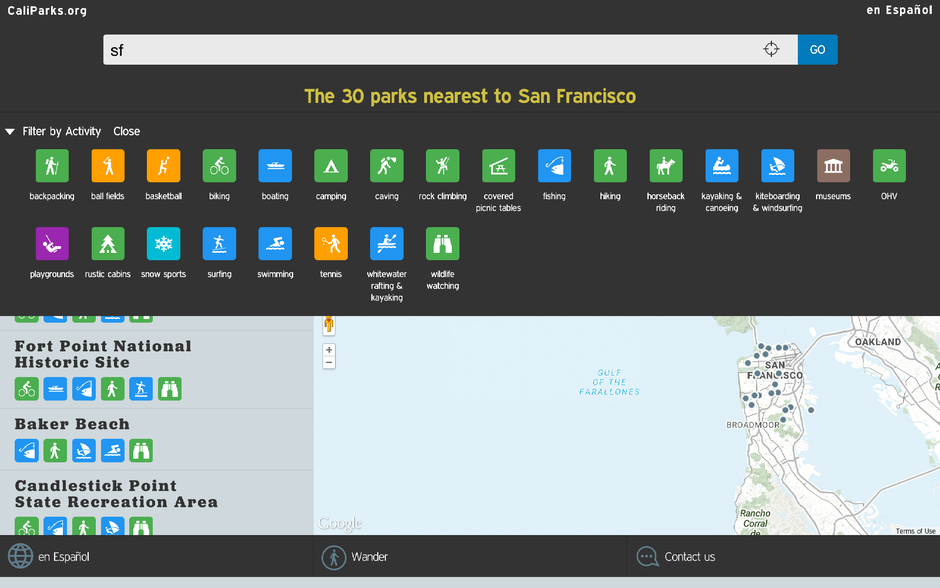

The app is the work of Stamen Design, a data-visualization design firm with deep experience in mapping and open data. CaliParks allows users to filter their searches based on proximity and desired activity, making it easy to discover even lesser-known parks. It provides maps and links to official park websites. But its real innovation is that it draws in images from Flickr and Instagram on a daily basis, giving users a dynamic portrait not only of a park’s natural beauty, but also of the way it is used by visitors. The app, designed in collaboration with GreenInfo Network, Hipcamp, and Latino Outdoors with support from the Resources Legacy Fund, also logs Twitter and Foursquare traffic relating to each park.

This part of the app's design, based on data pulled from more than half a million individual users, is calculated to overcome what the Parks Forward commission identified as one of the greatest barriers to park use. “It’s important for people to see people like themselves in public spaces in order to feel welcome there,” says Jon Christensen, a partner in Stamen. “Attendance in parks, particularly national parks, is not representative. Latinos, African Americans, Asian Americans are underrepresented. If we can harvest that social media and share it, that can be an invitation. We can present a more diverse California.”

The app also allows for easy browsing by desired activity or proximity to users. (CaliParks.org)

Christensen says that the app is also calibrated to fit the way that younger people are approaching their recreation choices. “We think, and anecdotally we see, that social media does skew much younger and more representative of the diversity of California,” he says. The inclusion of social media and open data, says Christensen, ensures that CaliParks is not “a walled garden,” but rather a dynamic and fluid interactive experience. Christensen says that refinements and modifications will be ongoing in months to come, and that down the road, a mobile-specific app could follow. Eventually, the app could also allow people to sign up for volunteer opportunities, pay park fees, and donate to help finance operations.

Christensen says that CaliParks simply capitalizes on the inherently friendly nature of parks. “Parks are social—people do things in parks that they do in the rest of their lives,” he says. “They take pictures, they take selfies, they meet up. It’s like people are having a party over there. We don’t have to gin that up. We just have to figure out how to participate in those conversations.”