I Fell in Love at a Sewage Treatment Plant

Kenneth Dellaquila / Creative Commons

Connecting state and local government leaders

A marriage of good looks and high efficiency, it has everything I could look for in great architecture—and my ideal Valentine.

The proposal was irresistible: Valentine’s Day at a sewage treatment plant.

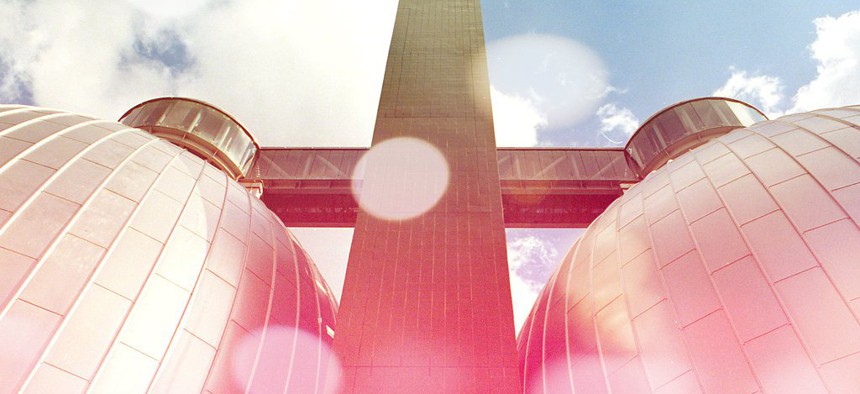

And indeed, with its eight towering silver eggs, like giant Hershey’s Kisses on the horizon, there is much to love about the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant in Brooklyn, New York. A marriage of good looks and high efficiency, it has everything I could look for in great architecture—and my ideal Valentine.

He’s sweet.

Now in its fourth year, the plant has been hosting sold-out tours of its facilities on Valentines Day. Love and sewage weren’t an obvious fit, but the tradition started by accident, says a spokeswoman for the Department of Environment Protection (DEP), Mercedes Padilla: “We used to conduct tours on the second Tuesday of each month, and in 2012 it happened to fall on Valentines Day,” she explains. “People loved it, and it’s been a tradition since.”

Each one of the 300 visitors this year was given a Valentine’s gift—a commemorative pin in the shape of a sewer cap and a Hershey’s chocolate.

So thoughtful.

The Newtown Creek staff working the weekend shift embraced the occasion, many wearing a pop of red under their uniforms. “I hope someone proposes here today. We could use some loooove,” said one staffer as visitors filed in.

Nice views.(Creative Commons / Garrett Ziegler)

No one has yet popped the question while touring the facility. But unimpeded vistas of Manhattan from the viewing deck on top of the facility—high above the slippery sidewalks and the grubby subway trek on a frigid February morning—offer a great excuse to fall in love with New York City all over again.

Harmonious.(NYC Department of Environmental Protection.)

He’s handsome.

The facility, which has won many design awards, has become a mecca for architecture and urban planning devotees. It’s also a favorite location spot for TV and film shoots, providing the backdrop to movies including Salt and Wall Street 2.

Nice profile.(Creative Commons / Upsidedown NYC)

The scheme of the plant was adapted from India, where the first anaerobic digester was built. The award-winning firm Ennead Architects served as the master planner, working with three environmental engineering firms.

At night, the sanitation plant transforms into a futuristic reverie, a spectacle created by the innovative lighting designer Hervé Descottes, also known for his work on the High Line in Manhattan.

Cleans up nicely.(NYC Department of Environmental Protection.)

He’s considerate.

As a large-scale industrial facility within a rapidly gentrifying residential neighborhood in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, its planners were aware that no one wanted to live next to a grisly sewage facility. “We’ve done everything possible to make it nice,” Richard Olcott, a partner at Ennead Architects, explained in a promotional video (video).

And strange as it might sound, this sewage treatment plant is really quite nice. One of the first things built during the renovation was a visitor center, an orange twisted cube building designed by installation artist Vito Acconci, where free public education programs are conducted year-round.

Super friendly.(NYC Department of Environmental Protection.)

The renowned sculptor George Trakas was commissioned to create a nature walk around the perimeter of the plant.

Likes nature.(Creative Commons / Julie)

Artsy.(Creative Commons / Seth Tisue)

It didn’t need to be that way, architect Marc Kushner points out in his book, The Future of Architecture in 1oo Buildings. “The city could have easily stuck with a utilitarian design, but instead it decided to put $4.5 billion into overhauling the outmoded and environmentally unsound wastewater treatment facility, following a design that is sensitive to the surrounding residential neighborhood.”

Lives in a hip neighborhood. (Greenpoint, Brooklyn)(Creative Commons / Kevin Burg)

He smells okay.

Admittedly, there’s a base note of methane gas, a farty hum that permeates the facility. It’s slight, but present. The plant’s mechanism mimics the human digestive system—transforming wastewater to sludge to clean water, and eventually releasing methane as a bi-product.

But it’s not as bad as it could be. “The smell in other plants can be overwhelming for workers,” explains deputy plant supervisor Philip Monaco. “This is very neutral, to me.”

Passionate. (Deputy plant supervisor and tour guide Philip Monaco)

He pitches in to clean up.

With a 54-hectare footprint, Newtown Creek is the largest of 14 wastewater treatment plants in the city, filtering 310 million gallons everyday from toilets, showers, sinks and storm water before sending it back to the East River. According to a 2010 DEP report, New York’s rivers have been cleanest in a century. So clean are the waterways that a floating public swimming pool is being planned on the East River for 2016.

Dreams big.(NYC Department of Environmental Protection.)

He’s changing the world.

An exciting initiative is in the works, to convert Newtown Creek’s methane byproduct to a bio-gas fuel that can power households in New York. It’s easy to swoon over the prospect of a zero-waste operation recycling its own waste, making the Newtown Creek not only a sanitation facility but also a green energy power plant.

“Imagine, the water you flush down the toilet in the morning could fire up your stove at night,” says Monaco, beaming.

If the plan is successful, it will reduce New York City’s annual carbon emissions by more than 90,000 metric tons and provide energy to heat over 5,000 homes.

NEXT STORY: Mobile momentum picks up in state and local gov