Rahm Emanuel's Moment of Truth

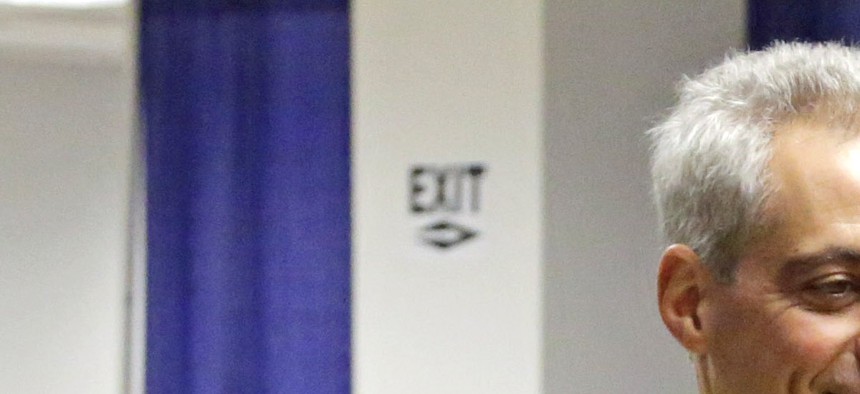

Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel walks from the polling booths after casting his vote early at the Chicago Board of Elections, Friday, Feb. 20, 2015. Emanuel faces four others in his re-election bid in the Feb. 24, 2015 mayoral election. M. Spencer Green / AP Photo

The Chicago mayor hopes voters will allow him to avoid an April runoff despite school closures and outbreaks of violent crime.

Too often, candidates run for office promising one thing and deliver another, alienating or simply disaffecting voters, and ultimately losing their offices. Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel faces a different sort of challenge: For the most part, he's given voters what he said he would. Now, do they want to keep it?

He'll find out Tuesday, when Windy City voters go to the polls in a mayoral election. Emanuel has mounted an extremely expensive, high-powered push to get past 50 percent of the vote—the threshold he needs to win reelection outright and avoid an April 7 runoff. The X-factor in the race seems to be black voters, so Emanuel has rolled out endorsements from high-profile African American politicians, including his former boss President Obama and Representative Bobby Rush, the only man to ever beat Obama in an election.

A Chicago Tribune poll last week showed that Emanuel was within striking distance of an outright majority, with 45 percent of voters backing him, and nearly 20 percent undecided. Emanuel's top opponent is Cook County Commissioner Jesus "Chuy" Garcia; other challengers include Alderman Bob Fioretti and businessman Willie Wilson.

It's been a rambunctious four years for Emanuel. After an election campaign in which he was nearly disqualified under residency requirements, the former U.S. representative and White House chief of staff cruised to victory. Since then, Emanuel has closed almost 50 schools; dealt with a strike by public-school teachers; passed an austerity budget for the city; and faced a significant murder rate. The bruising term has turned some voters off, especially after 22 years in which the city was led by the same man, Richard Daley. But in many ways, Emanuel has done just what he said he would, bringing his brusque, no-nonsense approach to the mayorship.

Long a pragmatic moderate who reveled in muscling his preferred strategies through—often with the aid of a generous helping of profanity—that's just what he's done, on issues ranging from the budget to education. Emanuel has exercised a control over the levers of power that exceeds even his long-tenured predecessor, bending the City Council and even the state legislature to his will. But that focus seems to have come at a cost: retaining support among voters themselves, who have grown chilly on Emanuel after giving him 55 percent of the vote four years ago.

Reaching the 45 percent mark is an accomplishment in its own right. Not long ago, Emanuel's polling was in the tank, and his reelection seemed in doubt. His rebound has been helped by two big factors: good luck, and piles and piles of money. First, two of his most formidable potential opponents bowed out. Two black candidates decided not to run—Toni Preckwinkle, president of the Cook County Board, passed, and Karen Lewis, a major Emanuel antagonist as head of the teachers' union, opted against running when she was diagnosed with a brain tumor.

Meanwhile, Emanuel has raised $15 million in the race, pouring much of it into television ads. His enormous war chest has allowed him to far outspend Garcia on the airwaves, who was unable to get TV time until the final two-week stretch of the race. In moving early to get on TV and bury his opponent, Emanuel is taking a page out of Obama's playbook in the 2012 presidential election, when he and allies spent early to "define" Mitt Romney for voters.

Still, black voters—who came out in force for Emanuel four years ago, in part because of Obama's backing—remain cool. In the Tribune poll, only 42 percent backed him this time around, with a quarter still undecided. That's in large part because minority neighborhoods have borne the brunt of Chicago's recent troubles. Most of the schools that closed are in those neighborhoods. Emanuel says that was actually for the better: The schools that were shuttered were underused and underperforming, and the closures should lead to students getting better educations. He also boasts of improvements like longer school days and more extensive pre-K programs. Horrific violence is also a major factor. Even as other cities saw big drops, there were 500 murders in Chicago in 2013, many of them concentrated in minority neighborhoods. (The number was down to 407 in 2014, a 40-year record low.)

If Emanuel has ridden Obama's coattails, his challengers have tried to emulate New York Mayor Bill de Blasio's example. As a technocratic, moderate Democrat who used a top-down style and has won plaudits from neoliberal pundits on issues like education, he seems to invite just the sort of left-wing campaign de Blasio used in his come-from-behind victory in 2013. They've even co-opted de Blasio's leitmotif, accusing Emanuel of overseeing a city divided into "two Chicagos."

Emanuel essentially admitted that was true in an interview with The New York Times. “‘The city that works’ has to work for everybody,” he said, alluding to a nickname for Chicago. “Have we made progress in areas that had developed for years? Yes. Is our work done? Absolutely not.” (Skeptics might note that he's been saying the same since his term started, and apparently hasn't finished the job yet. In a profile in The Atlantic in 2012, Emanuel told Jonathan Alter almost exactly the same thing: "We are known as ‘the city that works.’ You gotta make sure it works for everybody and not just a few.”)

The irony is that even as Emanuel risks losing voters, his hold on the city has been extremely strong—stronger even than Daley, by some measures. The mayor has managed to turn the city council into a "rubber stamp" for his policies, with aldermen backing him more than they did Daley or his father, who was mayor for 21 years.

If Emanuel can win on Tuesday, it might set him up for a tenure comparable to Daley pere or fils, perhaps even with more power. But most analysts are calling the contest too close to predict at this point, and if Emanuel wins only a strong plurality matters get murkier. Emanuel would retain the advantage of incumbency, fundraising, and backing from the national Democratic establishment. Yet Dick Simpson, an oft-quoted political scientist and former alderman, thinks Emanuel would be in trouble in a runoff: He'd suddenly look far more vulnerable, and national liberals would flock in to aid Garcia. (For the record, Simpson has contributed to Garcia's campaign.)

Hence the race to the finish for the mayor, as he spent aggressively and shook as many hands as possible in the last few days before balloting. Not that gladhanding is a pleasant task right now—as of writing, it feels like -14º F in Chicago. Tomorrow won't be great either, with the high barely reaching freezing and a forecast of gusty winds that should live up to Chicago's nickname. Bad weather tends to be a boon to incumbents. For a candidate who's already gotten very lucky, the forecast is one last stroke of fortune.

NEXT STORY: America's Most Economically Segregated Cities