Government of the Legislature, by the Legislature, for the Legislature

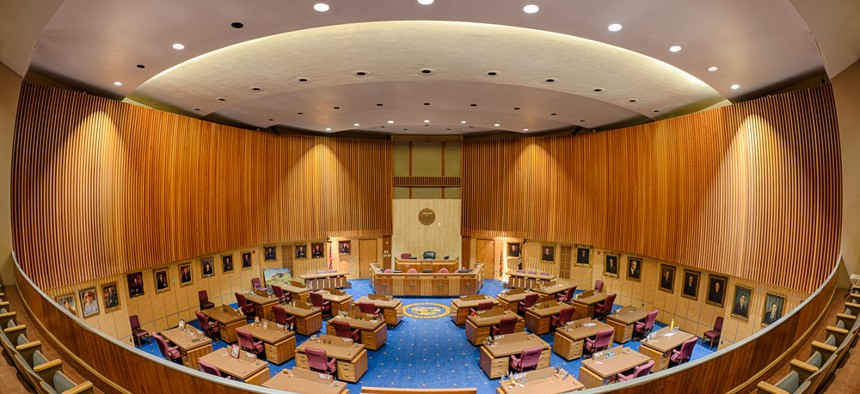

The Arizona Senate chamber. Nagel Photography / Shutterstock.com

The Supreme Court reviews Arizona's independent redistricting commission and considers whether voters have the right to draw congressional districts.

“If my fellow citizens want to go to Hell I will help them,” Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote to a friend in 1920. “It’s my job.”

But what if our fellow citizens are already in hell, and vote to spring themselves? Are today’s Justices required to block the exit?

That is one way to view the issue in Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, which was argued before the Supreme Court on Monday. Based on the questioning from the bench, a majority of the Court seems poised to answer “yes”—that Arizona voters violated the Constitution when they tried to rid their politics of partisan legislative gerrymanders. They did this in 2000 by passing an initiative creating an independent commission to draw legislative and congressional districts, with instructions to create competitive districts where possible. The commission is appointed by a complicated process, designed to make it independent. First, a panel that usually selects judges creates a bipartisan list of names. Then the majority and minority leaders of the two houses of the legislature pick four members, two from each party. Those four members then select a chair who belongs to neither party.

The commission prepares a plan and opens it for public comment. The legislature can file an objection—just like any other group—but it cannot veto the plan. The plan worked fine in its first go-around in 2001, but this time, beginning in 2011, the state Republican Party has fought against it at every step. Redistricting, they say, is their business alone.

Article One of the Constitution says that “[t]he times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by law make or alter such regulations.” What does that sentence mean? On Monday, the superlawyer Paul Clement spoke for the Legislature: “the words ‘legislature thereof’ means ‘legislature,’” he said. For the Commission, the equally distinguished Seth Waxman responded that when the Constitution was written, “it was understood that ‘legislature’ meant the body that makes the law.”

In Arizona, the people are part of that body, Waxman said. Article Four of Arizona’s Constitution reads, and has always read, that “[t]he legislative authority of the state shall be vested in the legislature, consisting of a senate and a house of representatives, but the people reserve the power to propose laws and amendments to the constitution and to enact or reject such laws and amendments at the polls, independently of the legislature.”

Previous Supreme Court cases have held that state constitutions can permit a governor, or the people at large in a referendum, to block a districting plan. But, said Clement, “it’s a completely different matter to cut the legislature out altogether.” That, he insisted, contravened “the judgment that the framers made.”

The initiative, referendum, and recall (the “Oregon system”) were conceived and adopted by many states only in the early years of the twentieth century. The Framers disliked what they considered “democracy”—mostly meaning adoption of laws by public meetings—but it’s less clear what they would think of the initiative process.

Could “legislature” include the people as a body? Here’s an analogy. Earlier this week I wrote about a lawsuit in Hawaii concerning the Seventeenth Amendment. One of the claims was based on the following language: When senate seats fall vacant, “the executive authority of such State shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies.” In the Hawaii case, the special election at issue had been called (as Hawaii law provides) by the state’s chief election officer. The plaintiffs argued that only the governor could issue the order.

That argument rightly gained no traction with the Court. The “executive” is a functional description. When the Constitution was written, many states had no “governor.” Some states had executive councils, some had presidents, and some had governors. Today, in almost every state, the word “executive” covers many different elected officials. One could argue that the term “legislature” is a functional term too, and includes the people if they reserve legislative power for themselves.

The counterargument is that the Constitution spells out that “the executive” of a state does certain things, “the legislature” does others, “judges” take a certain oath, and “the people” choose members of the House. The Framers believed in representative government, not democracy, this argument runs, and thus would want a legislative body to perform this delicate task.

History, as it does so often, provides evidence on both sides. “Obviously, we can point to our favorite quotes from the Framers,” Clement said. He cited praise for legislatures. An amicus brief for five of the most eminent historians of early America, however, points out that many of the Framers—particularly James Madison and Alexander Hamilton—distrusted state legislatures. They also knew, and discussed, the ways in which legislators could entrench themselves: “Whenever the State Legislatures had a favorite measure to carry,” Madison warned at the Constitutional Convention, “they would take care so to mould their regulations as to favor the candidates they wished to succeed”—a startlingly prescient description of partisan districting practices today.

Justices Samuel Alito and Antonin Scalia seemed to be firmly on the side of the Arizona’s legislature; Chief Justice John Roberts, too, seemed impatient with Waxman’s argument. Justice Elena Kagan took point for the Arizona system, joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Justice Anthony Kennedy seemed impressed with an argument drawn from the Seventeenth Amendment. Before it passed, states had tried to find ways to involve “the people” in choosing senators; but no one had claimed that the state could simply cut the legislature out of the process. “[T]hat history works very much against you,” he told Waxman.

Carefully read, Clement’s argument takes square aim at virtually all the independent commissions currently used by states. Commissions, he suggested, could only be used in two situations—“purely advisory” commissions, with no real power, or “backup commissions,” that could step in only if the legislature didn’t pass any plan at all. Legislatures, he said, must have “primary authority”—meaning, in essence, all power—and every commission plan must be reviewed on a “case-by-case basis.”

Justice Elena Kagan warned that Clement’s rule would lead to litigation in virtually every state that has commissions—and even in states that don’t, but which pass election laws, like Voter ID or Vote by Mail laws, by initiative. “I mean,” she said, “there are zillions of these laws.”

Clement warned that the Arizona plan fails because it “puts the state legislature on the same plain as the people.” Responded Waxman, “The gravamen of [the legislature’s] suit is that the people ‘usurped’ the power of a legislative body that they themselves created.”

The textual question is a genuinely hard one. For me, the tie-breaker is a provision no one mentioned: Article One of the Constitution says, “The House of Representatives shall be composed of members chosen every second Year by the people of the several States.” If the Court rules against the commission, we can confidently expect competitive congressional districts in Arizona to disappear. The people will have no choice in most elections, and that cannot be what the Constitution was understood to mean by its Framers.

Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein, two respected scholars of Congress, filed an amicus brief saying that commissions offer one of the few exit ramps from twenty-first century partisan hell. The two parties, they say, are adept in the use of legislative redistricting power to entrench themselves. “The consequences are twofold,” their brief says: “diminished electoral competition, which insulates Representatives from their constituents; and an increasingly polarized Congress that takes cues from the most extreme and politically active partisans, with little incentive to compromise.”

If the legislature wins, we can expect challenges to every other form of redistricting commission. Clement, however, told the other side not to despair: Article One applies only to federal redistricting. The people of Arizona are free to use commissions for their own state legislative districts. “If these commissions are as effective as my friends on the other side say,” Clement said, “then we will have nonpartisan districts that will elect … the state representatives, and the state senate, and then those nonpartisanly gerrymandered, perfectly representative bodies will be the ones to take care of congressional districting.”

(Image of the Arizona Senate chamber by Nagel Photography / Shutterstock.com)

NEXT STORY: Wyoming Ends Ban on Teaching Climate Science