The Department of Justice Is Asking Ferguson To Do the Impossible

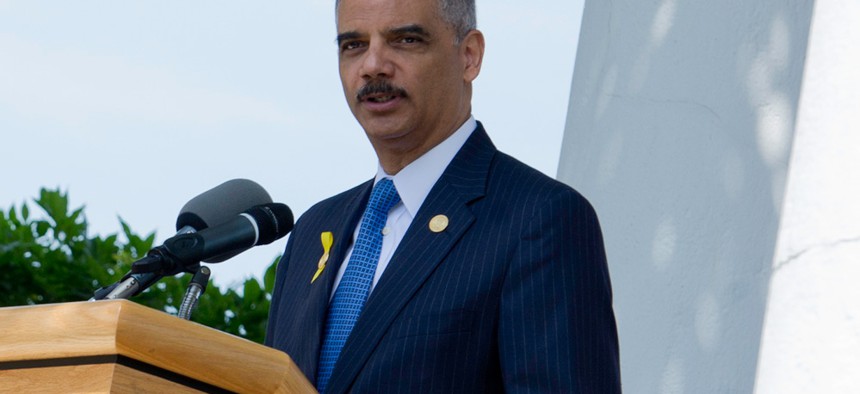

Defense Department file photo

Ferguson needs to drastically revise its court system. But how is a city supported by predatory court fees supposed to fund reform?

Yesterday, the U.S. Department of Justice concluded its civil-rights investigation in Ferguson, Missouri, issuing a scathing report on the practices of the Ferguson Police Department and the city's municipal court system. Today, the city's law-enforcement agency and justice apparatus begin the long road to reform. But the directives given by Justice to the police department and to the court may be at odds with one another.

Ferguson relies on court fees to fund its municipal activities. It's a well-documented fact that the collection of court fines represents a significant revenue stream for the suburb. A rapidly rising stream, too. Collections now account for one-fifth of total operating revenues and serve as the second-largest source of revenue overall. Last fall, Mother Jones and NPR detailed the many ticky-tack fouls that Ferguson officials call on residents—especially poor and black residents.

The situation is dire for many. "Despite their poverty, defendants are frequently ordered to pay fines that are frequently triple their monthly income," reads awhite paper by ArchCity Defenders, a legal nonprofit, on three egregious St. Louis County-area municipal courts, including Ferguson. Even Ferguson officials know it. One Ferguson Police Department commander described the futility of Ferguson's predatory collections scheme to Justice investigators with a saying: "How can you get blood from a turnip?"

That question may be turned on Ferguson officials now. Justice's recommendations for reforming Ferguson courts call for a vastly more sophisticated, professional court system than the one in place. At the same time, Justice's recommendations for reforming the Ferguson Police Department require it to focus far less on collecting revenue and emphasize protecting public safety instead.

So Ferguson needs to fundamentally revise its model for municipal governance. But how is the city supposed to pay for this work, now that the court can't raid the pockets of its residents?

Here's a rundown of the first 12 of the 13 recommendations from Justice for reforming Ferguson's municipal-court system:

1. Make municipal court processes more transparent

2. Provide complete and accurate information to a person charged with a municipal violation

3. Change court procedures for tracking and resolving municipal charges to simply court processes and expand available payment options

4. Review preset fine amounts and implement system for fine reduction

5. Develop effective ability-to-pay assessment system and improve data collection regarding imposed fines

6. Revise payment-plan procedures and provide alternatives to fine payments for resolving municipal charges

7. Reform trial procedures to ensure full compliance with due-process requirements (emphasis added)

8. Stop using arrest warrants as a means of collecting owed fines and fees

9. Allow warrants to be recalled without the payment of bond

10. Modify bond amounts and bond and detention procedures

11. Consistently provide "compliance letters" necessary for driver's license reinstatement after a person makes an appearance following a license suspension

12. Close cases that remain on the court's docket solely because of failure to appear charges or bond forfeitures

Many of these steps sound not-insignificant. How a city like Ferguson will find the funds to implement these reforms, when the plunder of poor black residents is no longer a revenue option, is a challenge. Any alternative is better than the status quo, of course, but the Justice reforms don't seem to anticipate that they might be structurally impossible for Ferguson.

As the Riverfront Times reports, the relationship between St. Louis County municipal courts and the poverty of the people living in those municipalities seems to be inversely proportional—meaning that the courts that are squeezing their residents hardest are also squeezing the poorest residents. Ferguson is among the worst in this regard: Unemployment in the city rose from 7 percent in 2000 to over 13 percent in 2010–12, per the Brookings Institution. One-quarter of Ferguson's residents live below the federal poverty line, while 44 percent live below twice the federal poverty line.

Court reform is more than a fiscal challenge for Ferguson. Step #7 among the recommendations from Justice is crucial. Looking back to the ArchCity Defenders' white paper for context on the justice system in Ferguson, this step seems totally beyond the city's ability to implement. From the white paper:

People who are arrested on a warrant for failure to appear in court to pay the fines frequently sit in jail for an extended period. No municipality holds court on a daily basis, and some courts meet only once each month. A person arrested on a warrant in one of these jurisdictions and who cannot pay the bond may spend as much as three weeks in jail waiting to see a judge.

[ . . . ]

Municipal court judges . . . are part-time positions. In St. Louis County, municipal court judges are often private criminal defense attorneys and sometimes county prosecutors. They may serve in multiple jurisdictions, and the judge need not be a resident of the municipality. Missouri does not prohibit, and some municipalities explicitly permit, practicing prosecutors and judges from one municipality to serve as a judge in another. Similarly, municipal court judges and prosecutors may be employees of the State working as a prosecutor in St. Louis County. It is possible for a defense attorney to appear before a judge on Tuesday who is the prosecuting attorney in another municipality on Wednesday. Later that week, that same person may be seen in practicing law in yet another role as a state prosecutor.

Guaranteeing due process in Ferguson would practically require building a working municipal court system from scratch.

And Ferguson is hardly alone in St. Louis County: It is just one of an absurd 89 municipalities coterminous with the county borders. ArchCity Defenders continues to beat this drum:

@NYTNational It's not just #Ferguson. pic.twitter.com/sN6JfZFfbP

— ArchCityDefenders (@ArchCityDefense) March 4, 2015"Each has its own municipal code, its own police force, and its own court," the white paper reads. "Eighty-one municipalities have their own court to enforce their municipal codes across their slivers of St. Louis County."

Yesterday, I wrote that Justice's review of Ferguson, however factually accurate and morally necessary, misses the forest for the trees. (And they are necessary: These guides will be reviewed by law-enforcement agencies far beyond the borders of St. Louis.) But it seems like the department's recommendations for reform are designed to extinguish the flames on one tree when the whole forest is on fire.

Here is the 13th and final recommendation from Justice for reform in Ferguson:

13. Collaborate with other municipalities and the State of Missouri to implement reforms

That's the whole ball game. But a generic guideline suggesting these municipalities "collaborate" doesn't go far enough.

Even if Ferguson were to get it right: Could Florissant? Where a part-time judge making two appearances per month earns $50,000 per year? Where the prosecuting attorney "works roughly 4% of a fulltime job, but earns 145% of a full-time public defender’s salary"? Could Bel-Ridge? Where 83 percent of the residents are black, 42 percent are below the federal poverty level, and warrants outnumber households 2 to 1?

These are just three of the cities in the greater St. Louis area where residents are suffering. Many of the municipal courts operating across St. Louis County may be too broken to be reformed. There is at least one potential solution to these structural problems: The cities could be reconstituted through unification. But that is a step toward reform that's beyond the Department of Justice.