Don't Expect to Ride in Driverless Buses Anytime Soon

A Minnesota Valley transit bus uses the shoulder on I-35W, outside Minneapolis; some of the fleet uses lane-assist technology. University of Minnesota

But partial autonomous technology can still improve transit systems.

Driverless cars are coming. Manufacturers like Mercedes-Benz and Ford andNissan are all-in. So is Google. So is Uber. Test sites are underway around the world. Intricate road maps are being developed and idiosyncratic driver profiles are being designed. The timelines might be optimistic, what with some expecting fully autonomous autos within five years, but the outcome feels inevitable.

Driverless buses: not so much. The Center for Urban Transportation Research recently surveyed transit bus manufacturers on their autonomous vehicle (AV) technology advances. The results were sobering:

Unlike the automotive industry which has invested a substantial amount of money into AV technology, there have not been similar AV developments in the transit industry.

Of the five bus manufacturers approached by CUTR— New Flyer/NABI, Gillig, El Dorado National, Nova Bus/Volvo, and Proterra—only one had ambitions toward enhanced autonomous technology. The exception was Nova/Volvo, which wants to develop a pedestrian-bicycle warning system for bus drivers. That's a potentially great advance in driver-assist technology, but nowhere near full automation.

The shame of it is autonomous buses could have enormous benefits for city mobility. As with all autonomous vehicles, bus safety would improve. Driverless BRT could be linked with driverless shuttles and walkable developments to create efficient commuter hubs in the suburbs. And at least with driverless trains, city agencies often find labor costs reduced enough to increase frequency and improve overall transit reliability.

Princeton's Alain Kornhauser and former New Jersey Transit planner Jerome Lutin recently examined the potential impact of smarter commuter buses in metro New York. They found that autonomous platoon technology, which lets vehicles run closer together, could enable some bus lanes to carry 205,200 passengers per hour into the city—five times the current load. Ridership gains of that magnitude could inspire cities to dedicate more lanes to buses, expand their sorry bus terminals, and otherwise invest in new transit initiatives.

CUTR highlights just two meaningful existing cases of transit operators implementing partial autonomous bus technology in the United States: a lane-assist program in Minnesota, and a BRT-docking pilot in Oregon. (Other testshave been promising but not adopted.) That's not a terribly encouraging start. But a closer look at the Minnesota program shows that metro areas can leverage autonomous features into transit gains even without going fully driverless.

Minnesota's Success With Lane-Assisted Buses

The Minnesota buses equipped with lane-assist technology offer a glimpse at the promise of driverless transit. Currently there are 10 such buses, operated by the Minnesota Valley Transit Authority, which shuttle commuters between Apple Valley and downtown Minneapolis. When highway traffic is particularly bad, these buses are allowed to run on the shoulder.

That's where the autonomous technology really comes into play. In the mid-1990s, while a researcher at the University of Minnesota, Craig Shankwitz began to develop the lane-assist system as a way to make sure vehicles could stay within the tight confines of the shoulder—especially in bad weather. (The technology is also used for snowplows in Minnesota as well as Alaska and California.)

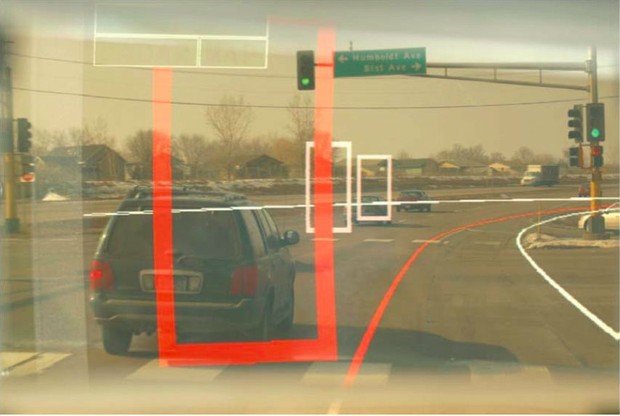

The bus lane-assist system, which uses GPS to locate its position and sensors to know its surroundings, has three levels of feedback. The first is a visual display that changes colors when a driver comes close to crossing a lane boundary. Then there's a seat vibrator that fires on whatever side the vehicle is veering toward; if the bus is heading too far left, for instance, drivers feel a vibration on the left side of their pants. Last, if the bus does go over a lane line, a torque motor tugs the steering wheel back toward the center.

Minnesota bus drivers can see when they're veering out of the shoulder. (Via CUTR)

That's a long ways from a fully driverless bus. But Shankwitz, who now works in the ground transport division of MTS Systems , a technology developer and tester, says it's the "same core technology." The difference is that the existing lane-assist system gives information to human drivers, instead of triggering an automatic vehicle response.

Despite being far from driverless, Minnesota's enhanced buses still provide plenty of mobility benefits. A Federal Transit Administration review found that the lane-assisted shoulder buses drove about 3 mph faster and had a 5-inch reduction in lateral movement. Riders were satisfied. Drivers in the general lanes, whether they realized it or not, faced less congestion. Excess road capacity was utilized, perhaps sparing taxpayers highway expansions.

So even in its limited form, autonomous transit technology can help metro areas. Still, says Shankwitz, "you're going to see human operators for a long time." The liability issues and public fears associated with fully driverless buses are just too great at the moment in his mind.

"I think the transition may be slower than it might be for passenger cars," he says. "It's not because the technology lacks. It's more the application."