States Rethink Laws Denying the Vote to Felons

Alexandru Nika / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

Election laws disenfranchise 5.9 million felons, but many states are rethinking those rules.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

When Republican Gov. Larry Hogan vetoed a Maryland bill that expanded voting rights, he angered a group of people who were never able to vote for him in the first place: felons still serving prison time, probation or parole.

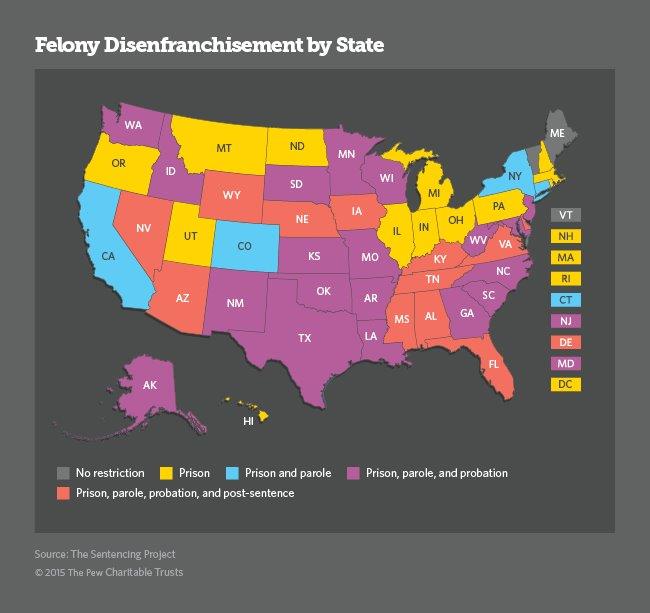

Maryland — like every state but Maine and Vermont — restricts the voting rights of felons. Some states bar felony inmates from voting, others extend the prohibition to offenders who are on parole or probation. Several states withhold voting rights from people who have been out of the criminal justice system for years.

More states are considering restoring the right to vote to felons, with supporters saying that once their debt to society is paid they should be allowed to exercise a fundamental right. This year, 18 states considered legislation to ease voting restrictions on felons; Wyoming was the only state to pass such a bill. That’s up from 13 states that considered bills last year, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Advocates for restoring voting rights argue there are practical reasons for granting felons a say in elections: Voting is an important step in becoming an active and productive citizen — and in reducing recidivism.

“[Disenfranchisement] is a very counterproductive message to send out,” said Marc Mauer, director of the Sentencing Project, a group that advocates for loosening the restrictions. “Recidivism is high. It should be the interest of the community to have a person reintegrated and connected with a positive institution.”

An estimated 5.9 million felons will be unable to vote in the 2016 presidential election. Several of the candidates — from both parties — have expressed support for restoring voting rights to many of them. In a tight race, felons with restored voting rights could very well tip the scale in some states.

U.S. Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky, who is running for the Republican nomination, has long pushed for his state, one of the more restrictive, to remove barriers to voting for felons. Last year, he testified in favor of a state bill that would have done that. U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina is another GOP presidential hopeful who favors easing restrictions.

On the Democratic side, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton introduced a bill to the U.S. Senate in 2007 that would have restored voting rights to those who had completed their sentence along with any probation or parole.

Barred for Life

Greg Carpenter was especially disheartened by the governor’s vetoing the Maryland bill that would have restored voting rights to former prisoners on probation or parole.He is one of an estimated 63,588 Marylanders who are unable to vote because of a felony conviction. And at 62, he is not sure he will live long enough to vote again.

Carpenter served 20 years in prison for armed robbery. Since getting out 12 years ago, he said he’s successfully transitioned back into society, and now works as a case manager helping people recently released from prison. He’s still in the middle of his 20-year post-prison parole, however, with eight years left. He hopes that Maryland’s legislators will override Hogan’s veto in January.

Wyoming’s new law gives the right to vote to felons who complete probation or parole, but not to those with multiple felony convictions or those whose crimes were violent. Starting in 2016, the state’s Department of Corrections will issue certificates of restoration of voting rights upon completion of sentence rather than requiring former inmates to wait five years before appealing to the parole board for one.

“Years ago, there was much stronger sentiment on not being soft on crime. But this year, it felt like the state and the legislative community was very open to it,” said state Sen. Leland Christensen, a Republican who heads the committee that drafted Wyoming’s law.

In Maryland, state Delegate Cory McCray, a Democrat, said many of his colleagues were moved to advance legislation by the testimony of Perry Hopkins, an African-American who missed the opportunity to cast his vote for the nation’s first black president, Barack Obama.

Hopkins said the day of the 2008 elections, he was outside celebrating Obama’s victory with others cheering in the streets of Baltimore.

“And then someone looked right at me and said, ‘If you didn’t vote, you shouldn’t be cheering because you didn’t help. You’re not a part of it.’ And it was a real solemn moment because he was right,” Hopkins said. “I couldn’t tell my grandkids that I helped make it happen. I was robbed of an opportunity to participate in history. All I could do was sit there as a witness. I’m worried the same thing is going to happen with Hillary.”

Pardon Practices

Despite growing calls to restore voting rights to felons, changes to state laws have come slowly. In Kentucky, the Republican-controlled Senate has voted down such proposals several times, despite support from Paul, a leading Republican.

Florida also has repeatedly rejected legislation to loosen restrictions, though an estimated 10.4 percent of its voting age population is barred from voting because of felony convictions — much higher than the national average of 2.5 percent. The state requires felons to wait five to seven years after completing their sentence, including probation or parole, before they can seek any restoration of rights. Those seeking a pardon must wait 10 years.

For a restoration of rights, applicants convicted of minor felonies, such as auto theft, must remain arrest-free for five years, while those with more serious convictions must write an essay and be cleared by the Florida Executive Clemency Board. If denied, they must wait two years before applying again.

“You shouldn’t be at the whim of a governor to be able to vote if you’ve served your time,” said Democratic state Sen. Christopher Smith, who has introduced legislation to loosen the restrictions every year since 1998, when he was in the House of Representatives.

Smith said his most strongly supported proposals were the ones that maintained voting restrictions for people on probation and parole or limited enfranchisement to those who committed nonviolent crimes.

Civil Sentence

Some corrections officials also advocate loosening restrictions. Steve Lindly, deputy director for the Wyoming Department of Corrections, said his state’s new law, passed this year, would help the agency achieve one of its foremost goals: helping people to be good citizens once they’re released from prison.

Restrictions leave felons without a say in electing policymakers they think are wrongheaded or those who impact the justice system with which they have become familiar.

“Those same judges that send boys and girls to prison for a long period of time, and I wasn’t able to cast my vote against them,” said Nicole Hanson of Baltimore, who has worked in politics for a decade, part of that time as an aide for state legislators.

Although she often helped register others to vote, Hanson has had to sit on the sidelines during elections because of a felony conviction for theft in 2011. And she had to let others take her daughters to the polls on Election Day to experience the voting process. That’s about to change, however. Hanson’s probation has ended, and she will be able to vote in the next elections.

Minnesota state Sen. Bobby Joe Champion, a Democrat, said that’s part of the reason he sponsored a bill scaling back voting restrictions on felons — so that youths don’t miss out on a positive example that will make them more likely to vote.

But Champion, a lawyer, said allowing felons to vote also helps respond to the wishes of the many victims who say, in victim impact statements, that they want those on trial to reform their ways, stay out of trouble and become positive members of their communities.

Hopkins, the Maryland parolee, said although he’s made great strides to become a positive member of the community since leaving prison, he feels like he’s still being punished because he is still denied the right to vote. “I’m serving a civil life sentence,” he said.

Rebecca Beitsch writes for Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

NEXT STORY: Mayor’s ‘Gorilla Face’ Obama Comments Pushes City Into Municipal Showdown