Philly 311: Innovation that was worth the wait

Connecting state and local government leaders

A funding crunch put plans for Philadelphia’s 311 non-emergency system on hold for years, but the payoff was better technology and new levels of citizen service.

Philadelphia’s 311 non-emergency system for information and service requests got its start on New Year’s Day 2008. At the time, plans for updates and expansions were scheduled for the next year and a half, but then everything stopped.

“It was supposed to take 18 months from start to finish, and it was supposed to be completed by spring 2009 and no later than the summer,” Rosetta Carrington Lue, senior adviser and chief customer service officer for the city’s managing director, told GCN. “We would have the centralized operations available, and phase two would be implementing more complex technology for better customer support. The third phase was for improvements based on what we were hearing.”

By the summer of 2008, however, the country had plunged into a recession, and city budgets were slashed. “We had to put phase two of the project on hold, which was the installation of robust technology,” Lue said. “So the original technology was supposed to be there only about four to six months, [but] six years later, we were still using this technology.”

Six years is a long time for technology, and social media exploded while Philadelphia’s 311 system was on hold. The system’s technology grew outdated and the office became understaffed, but in 2014 Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter got some funding and chose Philly 311 as one of eight technology projects to move forward.

Lue and her staff wanted to go beyond making simple upgrades. They wanted to change how residents made requests to the city and give them the ability to track those requests and give feedback on how the city responded to them.

“Our customers had a higher expectation on service delivery and response time, and they also wanted various channels to communicate with the city, meaning we had to look at what kinds of software can we use to implement that omni-channel experience,” Lue said.

And the city had an opportunity to track and use data. “We needed a system to help us analyze data and turn it into information very quickly in a time of crisis or a time of ongoing need where we needed to not just look at the data but show us trends, mapping, hotspots,” she added. Officials wanted a model that “would enable leaders to make a better decision based on the information they have in front of them versus waiting weeks for IT to organize all of it.”

With the help of Unisys, Lue and her team created a customer relationship management system based on Salesforce’s CRM platform. The system was released in December 2014 after 11 months of development, and it immediately changed the way residents make requests.

In the past, when Philadelphians called 311 with a service request, such as a pothole they wanted fixed, they would have no idea when the city would get around to addressing it, which led to frustration for residents and repeated calls to 311.

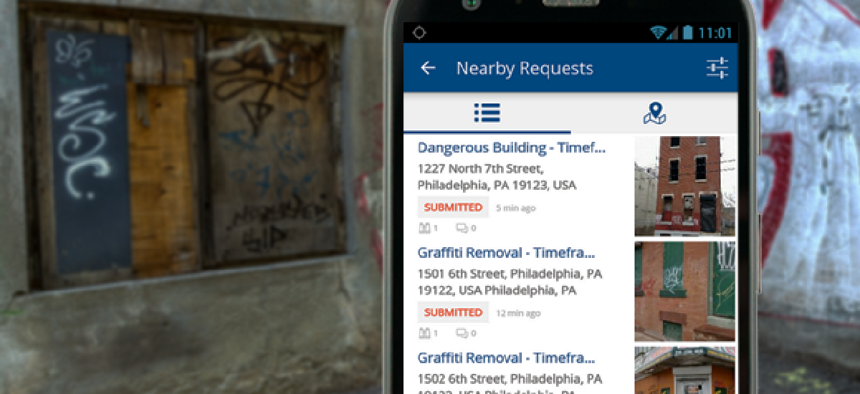

People can now make requests via phone, web or a host of social media platforms including Twitter and Facebook, and after a request is made, the person receives a timeline for resolving the issue and a tracking number to keep up with the request without having to contact 311 again.

“We’re giving our residents and customers the opportunity to report something and actually see what’s going on with your request,” Lue said. “That was important to the mayor.... [And] we have service agreements with the departments, so when you call in, we outline the process and set the expectations for you.”

Those service agreements are part of Philly 311’s efforts to better partner with other city departments on requests that are complicated or require a more in-depth response. One of the highlights of the new system is that police officers can now check on a citizen’s request right from their police cruisers.

“There are about 1,000 police vehicles” out in the city, Lue said. Anytime officers are talking to community members and hear about a 311 complaint that has not yet been addressed by the city, “the police can go back to their vehicle, put the address in and the information pops up.”

Lue wanted to make sure that the system would be easy for customers to use, so local citizens were involved in its design from the beginning. “We brought them in early in the process to help us, and that saved us time when it came to implementing the system and rolling it out,” she added.

Lue said the unplanned six-year hiatus allowed her staff and other city departments to study trends and new technology, and to make the best decisions once funding became available.

“Really it was a blessing in disguise,” she added. “We were able to bring about 100 people together from different city departments and say what we like and what we don’t like when it comes to the technology and getting things done. Those six years really gave us a chance to see how data was coming in and how it would be used, how we could be more efficient and effective. We were able to take all the lessons learned and say this is what we need as a city to ensure we have the right platform.”