Revenue Is Up in Most States; But Weak Forecasts Prompt Caution

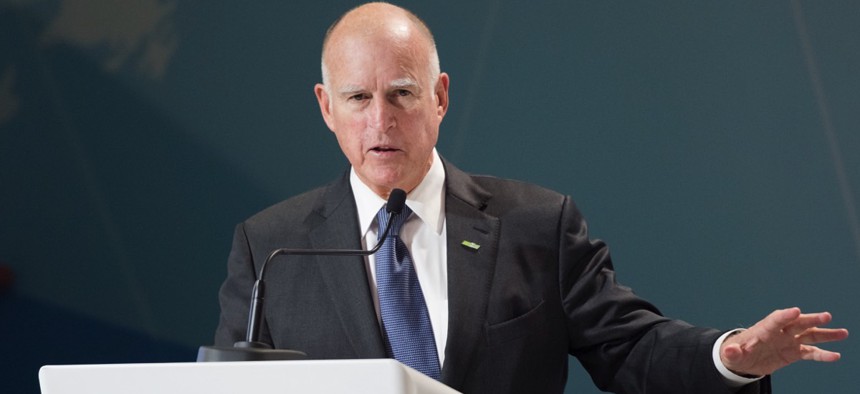

California Gov. Jerry Brown Frederic Legrand - COMEO / Shutterstock.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

Most state budgets are in the black this year, but many governors and legislators are reluctant to go on a spending spree.

This story originally appeared on Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Elaine S. Povich.

California should be popping champagne over a budget surplus, but isn’t. Virginia, another state with a surplus, wants to invest, but strategically. Meanwhile, Alaska and a handful of other states facing red ink are trying to figure out where to cut spending or what taxes to raise.

Most state budgets are nicely in the black, but predictions of weak economic growth are leading states to spend cautiously or to stockpile funds. And in the half-dozen states with red ink, lawmakers increasingly are looking to hike sales taxes, although they could be a weak source of revenue.

Many forecasters are predicting an economic downturn in the next couple of years, which has made many states reluctant to commit to big, expensive programs — even if they have a surplus. Recent volatility and losses in the stock market foreshadow less income tax revenue. And the trend in sales tax receipts is weakening, as consumers turn to untaxed Internet sales and cautious buying habits.

In legislative sessions that start this month, lawmakers face many demands for the revenue they have. Education spending, which has not returned to pre-recession levels in many states, is among the biggest demands. Transportation, health care and children’s welfare also are priorities.

Oil-patch states are struggling with budget shortfalls. As the price of oil plummets to $30 a barrel, lawmakers in Alaska, Oklahoma and Louisiana are seeing revenue from energy taxes shrink. But they aren’t alone in their budget concerns. Kansas lawmakers face more spending cuts, despite raising the sales tax last year. And lawmakers in Illinois, already mired in a deficit, still cannot agree on a budget for this fiscal year, let alone the next.

But most states have surpluses. And while that’s a good thing, optimism is tempered by tepid forecasts.

“State revenue forecasts for fiscal 2016 and 2017 are rather weak compared to 2015,” said Lucy Dadayan, senior policy analyst for the Rockefeller Institute of Government. “And many states are worried that states will continue seeing weakness in income and general sales tax revenue collections, in part due to changes in demographics and changes in consumer spending habits.”

According to the Rockefeller Institute’s “State Revenue Report,” issued in November, state tax revenue grew by 6.8 percent in the second quarter of 2015, the final quarter of the fiscal year for 46 states.

The growth was led by increases in personal income taxes. Sales tax collections in the April-June quarter grew 3.2 percent from the same period in 2014, which is significantly weaker than the growth reported in the previous four quarters, the report said. “Overall the average growth rate in sales tax collections is low by historical standards,” it said.

Income tax volatility is figuring into most states’ budget calculations, according to Brian Sigritz, director of state fiscal studies for the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), which surveys all states on their budget situations.

In its most recent survey in the fall, NASBO predicted “modest state tax revenue growth in fiscal 2016.” A big reason: The stock market’s increased volatility has left states unable to count on income tax windfalls that they have experienced previously.

The prospect of slow revenue growth is forcing states to “make tough choices going forward,” Sigritz said. “A lot of spending is going to health care and education,” he said, “and that doesn’t leave a lot for the rest of the budget.”

California Smilin'

California, the nation’s most populous state, led the pack in the rise in personal income tax revenue in the second quarter of 2015; it was one of five states with more than a 20-percent increase, according to the Rockefeller Institute report. Collections grew by $4.9 billion, or 20.6 percent. The extra money prompted California to invest in education and infrastructure.

But Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown is warning lawmakers not to get swept up in surplus fever; he proposes making extra deposits into the state’s Rainy Day Fund to prepare for worse economic times ahead.

“The next recession, even if it were only of average intensity, would cut our revenues by $55 billion over three years,” Brown warned in his State of the State speech Jan. 21. “That is why it is imperative to build up the Rainy Day Fund … and invest our temporary surpluses in badly needed infrastructure or in other ways that will not lock in future spending.”

Brown’s proposal isn’t sitting well with some lawmakers, who see urgent spending needs.

State Sen. Holly Mitchell, a Democrat who represents a district where nearly 40 percent of the children live below the poverty line, chairs the Budget Subcommittee on Health and Human Services. Mitchell said early childhood education and services are in greater need of the money than is the Rainy Day Fund: “The point is that for many Californians, it’s raining now.”

H.D. Palmer, spokesman for the California Department of Finance, said Brown’s caution is based in part on history. Most post-World War II economic expansions in California have lasted five years, but the current expansion has lasted two years longer.

“The governor is extremely mindful that these revenues can be fleeting,” Palmer said. “We know our turn in the barrel is coming, we just don’t know when.”

Virginia Targets Education

Virginia is enjoying its biggest surplus ever, and Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe wants $1 billion of it in his proposed $109 billion budget to go to a “new investment” in education — both K-12 schools and public colleges and universities. He also proposes a modest cut in the corporate tax, from 6 to 5.75 percent, and investing in business promotion.

“We need to fill the skill sets for the jobs we have today,” he said this month at a National Governors Association (NGA) forum in Washington. “It’s not throwing money at problems; it’s strategically investing in new ways.”

Other states that have a surplus can expect fights over what to spend the money on.

In Minnesota, for instance, having surplus money has prompted Democratic Gov. Mark Dayton to drop talk of a possible increase in the gasoline tax to fund transportation. In Arizona, the Legislature is expected to argue over whether to cut taxes or restore money recently cut from K-12 education.

Tax Trends

Most states haven’t splurged in recent years. The revenue hasn’t been there for it. And the prospect of slower economic and revenue growth ahead makes it harder for the states that face deficits to solve their problems without a tax increase.

Before the Great Recession that began in 2007, state revenue increased an average of 5.5 percent a year, said Scott Pattison, executive director of the NGA.

“In the recovery years, you are lucky to see a growth rate of over 4 percent,” he said. “That is forecast to continue.”

Exacerbating the problem for states is that the often more politically palatable sales tax isn’t delivering the payoff it traditionally has. Sales tax collections are projected to increase by 3.9 percent in fiscal 2016 after growing 5.2 percent in fiscal 2015, NASBO projects. That can leave lawmakers in some states looking to more spending cuts or the politically unpopular income tax to close budget holes this year.

Alaska, which hasn’t had an income tax for 35 years, is looking at one as its oil tax revenue plummets. Independent Gov. Bill Walker has proposed a personal income tax of 6 percent of federal taxes to help the state dig out of a $426.9 million deficit.

Walker also is calling for revising payments from the state’s unique “permanent fund” that pays Alaska residents annual dividends from oil royalties. That revision would reduce the dividend checks to $1,000, from $2,072 in 2015.

That combination would leave Alaskans with less money in their pockets, which doesn’t sit well with some lawmakers.

State Sen. Anna MacKinnon, a Republican, suggests more spending cuts before taxes are raised or dividend payments are cut: “I disagree with the governor [who wants] to hold harmless the biggest cost drivers, K-12 education and Medicaid.”

Louisiana, another energy-producing state, is in similar straits with a $1.9 billion budget shortfall expected for next fiscal year. Newly elected Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, is proposing a variety of solutions, including increasing the state’s 4 percent sales tax to a nickel on the dollar, hiking cigarette taxes and overhauling corporate taxes.

But just like in Alaska, some lawmakers are leery of tax increases. Rep. Lance Harris, chairman of the House Republican Legislative Delegation, said he is “not one to be inclined to pass a sales tax” because “it would put us very high compared to the other states.”

“We have to make sure that we drill down into the spending side of the equation as far as we can go,” he said.

(Photo by Frederic Legrand - COMEO / Shutterstock.com)

NEXT STORY: Kentucky’s New Governor: Ignoring ‘Our Financial Problems Is No Longer an Option’