Faced With Staggering Backlogs of Rape Kits, States Change Testing, Investigations

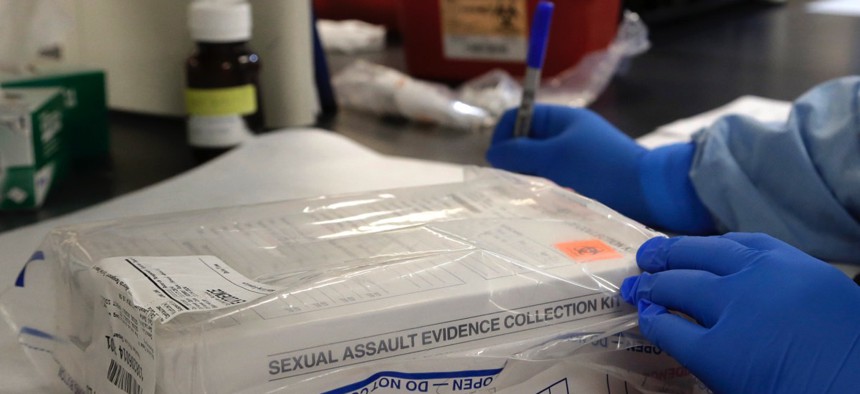

A sexual assault evidence kit is logged in April in the biology lab at the Houston Forensic Science Center. Pat Sullivan / AP Photo

The discovery of tens of thousands of untested rape kits has prompted many states to test them or set more stringent standards for handling them in the future. But is that enough to solve cases?

This article was was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Rebecca Beitsch.

Seeking to secure justice for thousands of rape victims, about 20 states are moving to test a backlog of unexamined rape kits found in storage rooms in police departments across the country — and change the rules for how rape cases are handled in the future.

Some states, including Colorado, Illinois, Ohio and Texas, already have passed laws that require that old kits be tested, and have seen charges brought against suspects as a result. In several states, including Michigan and Tennessee, law enforcement agencies face new time limits for submitting rape kits for testing. In others, law enforcement agencies were ordered to make a full count of their backlogged kits before state officials decide how to go about testing them.

This year, Arizona, Hawaii, New Hampshire and New York are considering bills that would require an inventory of backlogged rape kits. Oregon is considering legislation that would require testing the old kits, and Massachusetts, New Jersey and Rhode Island are considering bills that would require both, according to the Joyful Heart Foundation, a nonprofit founded by actress Mariska Hargitay of the "Law and Order: Special Victims Unit" television program and which advocates for the testing of all rape kits.

The goal of all the legislation is to ensure that forensic evidence in the kits, such as DNA that is collected from victims in an invasive process that can last four to six hours, is promptly and properly tested to help identify and prosecute suspected rapists. The DNA evidence is placed in an FBI database so that it can be compared to that of criminals and suspects who’ve had theirs taken.

“For someone to have survived a rape, reported it to police, and endured the invasive evidence collection, only to have it sit in an evidence room untested—I find that appalling,” said state Rep. Janet Adkins, a Florida Republican who is sponsoring a bill that would require faster testing of new rape kits.

The exact number of untested rape kits across the country is not known, but indications are it’s staggering. The Joyful Heart Foundation initially documented about 140,000 kits in the 27 states for which it has data. But Ilse Knecht, the group’s policy director, said old kits are continuously being discovered. Last week, for instance, Honolulu police officials said they had a backlog of 1,500 rape kits dating back more than a decade. Florida officials said in January that nearly 13,500 untested kits had been found across the state.

“We don’t really have a figure for how many kits there are, and that’s a symptom of the problem,” Knecht said.

Backlogs often grew over the years because testing is expensive and labs with limited capacity can be forced to address some cases over others. Older kits piled up because evidence collected in the 1980s was used to run blood tests — something that happened only when there was a suspect to compare it with.

Advocates for rape survivors say the kits also piled up because rape cases weren’t investigated seriously. “The bigger problem is not that they chose not to test the kit but that they chose not to investigate the case,” said Rebecca Campbell, a professor at Michigan State University who helped Detroit assess its backlog.

While many states have intensified their efforts to deal with their backlogs since discovering them, investigators and prosecutors stress that testing the kits can be meaningless without police following up on them.

“Some people are just testing the kits, and I don’t get that approach at all,” said Kym Worthy, Wayne County, Michigan, prosecutor, which had a backlog of 11,000 in 2009, much of which was from Detroit. “It’s great to test the kits and it puts information in the [FBI] database, but it does nothing for justice.”

Testing Pays Off

So far, just Colorado and Illinois have cleared their backlogs.

But some cities have taken action. Detroit and Houston began testing kits as part of a federal National Institute of Justice program that required them to study how the backlogs were created and how to avoid them in the future.

The cities sent the kits to private labs for testing because state or local police labs were overburdened. Houston spent $4.4 million to send its backlog of 6,600 kits — some of which dated to the 1980s — to two private labs in 2013. When the testing was completed, comparisons with the FBI database that contains DNA profiles of more than 12 million offenders and suspects led to 66 new charges. The results also helped police confirm 132 previous arrests that were made without DNA evidence.

Detroit, which received $7 million from the state to test its backlog, has seen the number of untested kits drop from roughly 11,000 to 1,000, according to the Wayne County prosecutor’s office. The kits helped identify 729 suspects and ultimately led to 36 convictions.

By testing the kits and entering the results into the FBI’s database, police aren’t just coming up with new suspects in old cases — they’re connecting them to cases in other states and jurisdictions and mapping out the paths of serial rapists. “Rape kits in just one city and one county have tentacles in 39 other states,” Worthy said.

When Detroit first decided to test its backlog, Campbell of Michigan State University said some people involved with the project were uncertain whether they should test kits that were beyond the statute of limitations. The state eliminated the statute of limitations for rape in 2001. But for most cases older than that, prosecutors had six years in which to bring charges. There also were questions about whether it made sense to test kits in cases in which a victim knew her attacker or focus instead on “stranger rape” kits.

Testing of the first 2,000 kits in Detroit showed why it’s important to test all the kits, Campbell said. There were just as many hits on the FBI database in older cases as in newer ones, and the kits from acquaintance rapes got just as many matches as stranger rape cases. Just because a rapist is known to the victim, doesn’t mean it’s not worth checking to see if he was responsible for other crimes, Campbell said.

Looking Back vs. Looking Forward

Many states that want to reduce their backlog start with an inventory of police vaults and evidence rooms, which the New York Legislature is considering requiring.

Assemblywoman Linda Rosenthal, a Democrat who sponsored the New York bill, said it’s important to understand the scope of the problem to decide how to fix it. Texas required a count in 2011, and, after about 20,000 kits were found, the Legislature in 2013 set aside nearly $11 million for testing.

Audits can help states decide whether they can handle the tests within state labs or need to contract with a private lab, where it can cost $500 to $1,500 to test a kit. Colorado spent $2.7 million to test its 3,500 backlogged kits in private labs.

States also are acting to ensure new backlogs don’t occur.

Michigan passed legislation that gives police 14 days to get kits to the lab and requires labs to test the kits within three months, as long as they have sufficient staff to do so.

Colorado mandates that all new kits be tested, with law enforcement required to submit them to the state lab within 21 days. It’s something Janet Girten with the Colorado Bureau of Investigation, which tests the kits, said is essential for making sure the state never has “a backlog of kits unanalyzed in law enforcement vaults.”

But the mandate also creates three to four times the workload the lab had when police departments sent kits on a case-by-case basis, Girten said. To help deal with that, the state set aside $5 million annually for the lab to hire 16 more scientists.

Last year, Tennessee passed a bill that gives law enforcement 60 days to submit a kit for testing and requires a state task force to come up with a new policy on investigating rape cases.

Other states are considering similar legislation this year. A Florida bill, for instance, would give law enforcement 30 days to submit a kit to a lab, and labs would have 120 days to test it. A Kentucky bill would give law enforcement 30 days to submit the kit, but it puts more pressure on labs to speed up testing over time. Labs would need a 90-day average testing time by 2018 and a 60-day average turnaround by 2020.

Beyond the Lab

Investigators, prosecutors and victims’ advocates say that while testing rape kits is important, more needs to happen to bring justice in cases of rape.

Both Cleveland and Detroit have set aside people to work solely on backlogged cases, using a mix of local, state and federal funds to hire more investigators and prosecutors.

Rick Bell, assistant prosecutor in Cleveland’s Cuyahoga County, said his team spends an average of 40 hours following up on a case once an old kit gets tested. Even with about 25 people looking into old cases in Cleveland, Bell said, it will take years to go through them all. But the investigations have led to 136 convictions, and those people are serving an average of about 10 years, he said.

Support for Victims

The push to get kits tested has also put a spotlight on victims, how they are treated by police and how to give them justice.

Collecting the evidence is very involved and invasive, with victims naked in front of a stranger while their bodies are combed and swabbed for evidence.

“It’s a lengthy exam and hours of questioning when all they really wanted to do was go home and shower,” said Knecht of the Joyful Heart Foundation.

Several police departments have adopted new policies for investigating rapes. In Houston, advocates are available to help guide victims through the justice system and efforts are made to accommodate a victim’s gender preference for an investigator.

Some entities are also looking at ways to track the kits. Detroit now has bar codes on all its kits that police can use to monitor them.

Washington is considering a bill that would impose a $4 state tax on people who enter a strip club, with the money used, in part, to pay for a tracking system that the bill’s sponsor, state Rep. Tina Orwall, a Democrat, would like to make accessible to victims. Orwall said the proposal would help the state monitor law enforcement’s progress and is “a great way to be accountable to victims.”

NEXT STORY: Colorado Debates a Major Health Care Overhaul