How Missouri police deliver on-scene interoperable communications

Connecting state and local government leaders

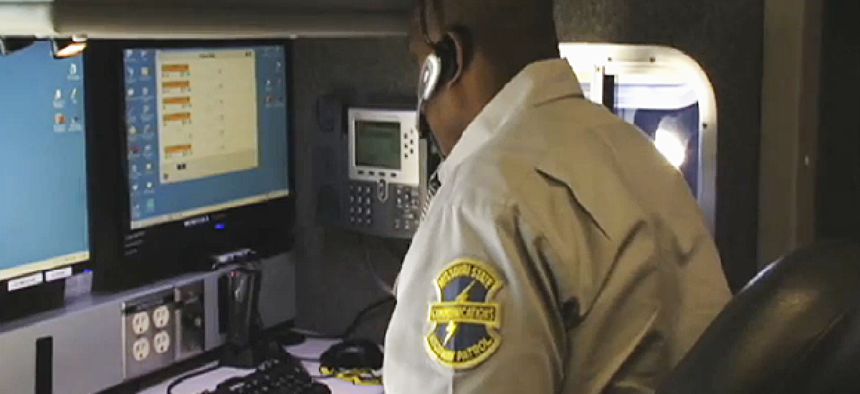

The Missouri State Highway Patrol’s command and control vehicle uses a system that allows for TCP/IP communication across P25 networks.

A specially equipped command and communications vehicle is helping the Missouri State Highway Patrol (MSHP) overcome a chronic problem for law enforcement officials and first responders: interoperable communications.

The vehicle acts as a central processing center for communications, allowing the MSHP to communicate with state and federal agencies, from local sheriff’s departments and fire departments to the U.S. National Guard. MSHP’s command and communications vehicle is outfitted with Cisco Systems’ IP Interoperability and Collaboration System (IPICS), which bridges communications networks and lets officials talk to one another directly. Specifically, it allows for TCP/IP communication across P25 networks that use the Interswitching System Interface protocol.

For example, when MSHP responded to unrest in Ferguson, Mo., following the fatal shooting of an unarmed black teenager by a white police officer in 2014, it brought the vehicle and used it to bridge communications among three disparate systems. MSHP was operating on a new P25 radio system, while the city operated on an older P25 version, and the county agency used a wideband system instead of narrowband like the other two. Using IPICS, MSHP was able to join the three disparate systems within minutes and allow the agencies to communicate easily.

“It’s really important for us to deliver communications, not just for our agency, but for all the agencies that are involved in that situation,” said Lt. Les Thurston, assistant director of MSHP’s Information and Communications Technology Division. “We had to come up with a solution that allowed us to make that gap transition so much easier.”

Before IPICS, responders would call MSHP’s truck using whatever devices and systems they had, talk to an operator, and the operator would transmit the information out under MSHP’s signal. Besides creating considerable latency in information sharing, specifics often got lost in translation, Thurston said.

Now, IPICS takes the signal, ports it to the vehicle, bridges it and allows the channels to talk to one another all within split seconds, virtually eliminating lag times. “It makes the communications so much more effective,” Thurston said.

Other features of IPICS include radio signaling, such as talker ID and private calls, and an option to have end-to-end encrypted calls with dispatchers.

Technicians in MSHP’s vehicle set up the IPICS patch, finding the frequencies and patching them together. As long as the radios operate on frequencies that are common to public safety, the tool can patch them together, he said.

Officers on the scene don’t have to do anything. The vehicle receives the signal from one agency “and then it patches together and broadcasts it back out for everybody to hear,” Thurston said. “It’s a short-term system for one radio system to be created on-scene.”

MSHP got the communications vehicle in 2009, but it got its first real test drive after a powerful tornado hit Joplin, Mo., on May 22, 2011, killing 158 people and causing about $2.8 billion in damage. “We saw its greatest potential in Joplin,” Thurston said. “When you can see it there, creating communication that’s really seamless for the officers there, man, that’s really gratifying.”

IPICS -- soon to be rebranded as Instant Connect -- is an amalgamation of several Cisco technologies, including voice over IP, an interface with legacy communications systems, conferencing and interactive voice systems.

“We looked at it as an open standards platform for collaboration,” said Kevin McFadden, a solutions architect at Cisco’s public-sector team. “We focused that collaboration on voice, and we found that there was a great applicability toward what we call push-to-talk voice.”

IPICS allows users to have different endpoints involved in push-to-talk communication. “Those endpoints are as familiar as a laptop computer on your desk, maybe completely away from any of the land-mobile radio communications – it could be thousands of miles away and still be interactive with the people using the radios,” McFadden said, adding that the endpoints could also be smartphones or tablets.

Because spectrum is scarce -- and the land mobile radios operating on it are costly -- the number of people who can use it is usually low. But IPICS “allows us to move some of those communications into the IP world, which isn’t constrained by those same spectrum issues,” McFadden said.

What’s more, IPICS is scalable for use in small areas or nationwide. Once IPICS is integrated with a radio system, he explained, “we can reach any place that the IP packet can reach, which can be worldwide, if appropriate.”

Looking forward, Thurston said IPICS will need to support the First Responder Network Authority’s Nationwide Public Safety Broadband Network and Band 14.

McFadden said the system will be ready. Because IPICS is IP based, it will be available when FirstNet comes online for first responders, he said. Communities should “start changing their concept of operations, how they use IP-based communications like IPICS to evolve their processes.”