The U.S. Civil Rights Commission Is Investigating the EPA

EPA file photo

The agency has not enforced policies in Chicago that protect minorities and and low-income families from deadly pollution.

The Flint water crisis is an environmental justice issue, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Secretary Gina McCarthy told community activists on a March 10 conference call, where she assured them the agency won’t be leaving Flint until the problem is resolved.

“It’s clear to me that this problem is really all about money, a lack of investment in underserved communities,” McCarthy said.

As that call was taking place, the National Environmental Justice Conferencewas going on in Washington, D.C., where McCarthy later delivered a keynote address reiterating these comments about Flint. McCarthy is not incorrect about the role of money in the city’s water crisis. Flint has become the national symbol for economically distressed cities. But as CityLab’s Laura Bliss has reported, the Flint crisis is also about paltry law enforcement. This holds especially true regarding laws that are supposed to protect communities that have historically suffered from discrimination and disinvestment. The EPA hasnot been up to that task, as The Center for Public Integrity has reported—which is why the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is now investigating the agency.

Members of the civil rights commission were in Chicago for a public hearing on March 9 to gather information about why minorities have long suffered from a disproportionate amount of health-endangering pollution in the U.S. Much of the focus at that hearing was on Waukegan, a small city just north of Chicago where over half of the population is Latino and about 20 percent is African-American. Waukegan residents recently testified about a coal-burning plant that’s been running just steps from the front porches of many black and Latino families’ homes for decades.

The NRG Energy coal plant deposits its coal ash waste in ponds around Waukegan, which has worried residents about contamination of their groundwater. The plant has been operating for almost a decade without a final permit for the pollution it releases, as is required under the Clean Air Act.

As Kari Lydersen reported for Midwest Energy News, the EPA’s environmental justice director for Illinois, Kenneth Page, testified at the hearing that he was “not exactly sure” why NRG has been operating without this permit. Waukegan alderman David Villalobos and community organizer Dulce Ortiz raised a number of issues at the hearing about broken promises made by NRG Energy about its pollution. But with lax enforcement of these laws, the company has not been held accountable. Writes Lydersen:

At the hearing, Villalobos and Ortiz testified that they want state regulators to demand stricter pollution controls on the Waukegan plant, and to press the company to make clean-up and transition plans in case the plant closes. “To actually enforce our existing laws, while strengthening policy,” as Villalobos said to the committee.

The U.S. Civil Rights Commission will use these testimonies for its investigation into whether the EPA is fulfilling its obligation under the Civil Rights Act, which is to protect disadvantaged communities from bearing an unfair burden of pollution. Every year, the civil rights commission picks a topic to probe for evidence of whether the federal government is adequately enforcing civil rights laws. The commission chose environmental justice for 2016, and will conduct a number of public hearings throughout the year in its investigation, mostly looking at the effects of coal ash and fracking on minorities and poor families.

The civil rights commission’s first hearing of the year was in Washington, D.C. last month, where the panel grappled with whether the EPA abided by civil rights statutes in developing new rules on coal ash waste disposal, which were finalized in 2014.

Uniontown, Alabama, which is 90 percent African-American with a median household income of $13,800, figured prominently in that day’s discussion. It’s the location of Arrowhead Landfill, where millions of tons of coal ash wastefrom the 2008 Tennessee Valley Authority coal ash spill disaster has been stored. Esher Calhoun, an elder resident of Uniontown, testified that she and her neighbors regularly receive visitors who come to see “that big mountain of coal ash,” and have voiced their concerns at numerous townhalls.

“But nobody is doing anything,” said Calhoun. Explaining what life is like for her, she told the commission:

The landfill sits across the street from where people live, where my friends and neighbors have lived for years. I used to live right there across the same road from where the landfill is now. I understand this community. You have to understand the rural way of life: People sat on their porch and enjoyed the air, and they talked to each other. Now they live across the street or down the road from the landfill and it smells. Their property isn’t worth what it used to be and their children don’t want to come back here. No one wants to buy land near the landfill. People no longer let their grandchildren play in the yard without fear. The smell, the pollution, and the fear affect all aspects of life—whether we can eat from our gardens, hang our clothes, or spend time outside. This isn’t right.

Lisa Evans, an attorney for the environmental-law nonprofit Earthjustice, wrote in a statement to the commission that the EPA finalized its coal ash disposal rule in a way that asks states to comply with it, but only on a voluntary basis. This means, writes Evans:

The only means of enforcement is by citizen suits, which can be brought by citizens or states. EPA has absolutely no enforcement authority.

EPA’s decision to issue an entirely self-implementing rule—where state enforcement is completely voluntary and compliance will largely be enforced through citizen suits by affected communities—has dire consequences for communities of color and low-income communities. First, these communities generally have far less access to the legal and technical resources necessary to provide oversight of coal plants in their neighborhoods. Because of the complexity of the coal ash rule’s requirements, an evaluation of compliance will often require the assistance of individuals with technical expertise.

These consulting services, especially if licensed engineers are required, are very expensive, and the costs are clearly out of reach for most communities. In addition, if and when violations are found, communities of color and low-income communities have substantially less access to the legal resources necessary to pursue citizen enforcement in federal court—the only recourse for enforcing the coal ash rule.

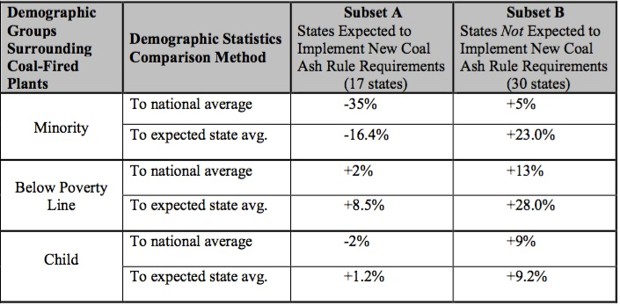

The table below, created by the University of Maryland’s Center for Progressive Reform to accompany Evans’ written statement, shows how these racial disparities may play out: “The minority populations near coal plants are 5 percent higher than the national average, and 23.5 percent higher than their respective statewide averages in states that are not expected to adopt new controls.”

(Center for Progressive Reform at the University of Maryland School of Law/Earthjustice)

These civil rights commission hearings are far from the first time the EPA has been called out on its civil rights enforcement duties. Former EPA Chief Lisa Jackson commissioned an assessment of the agency’s civil rights work in 2011, which made the same scathing critiques. The agency has been working in recent years to improve its enforcement mechanisms, but the Flint crisis is evidence that change is coming too late.

EPA officials knew for at least a year that there were troubling signs of toxic lead in Flint’s water system, and failed to push the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality to do something about it. That’s how the federal hands-off, leave-it-to-the-states approach leads to these kinds of disasters.

On the EPA’s March 10 conference call with environmental justice advocates, representatives said agency staff is in Flint in full force, delivering fact sheets and answering residents’ questions about when it will be safe to bathe in and drink the water. But this is well after the fact, and after the injuries. Flint residents had plenty of facts coming out of their spigots over the past two years in the form of toxic pudding. They spoke out about it. No one listened to them.

Perhaps the civil rights commission investigation will turn the EPA into better listeners, though people probably don’t have their hopes up. This is the second investigation conducted by the civil rights commission on the EPA’s environmental justice obligations in the past 15 years. The last investigation, in 2003, led to a long list of recommendations, among them:

EPA should condition approval of state programs, which administer federal environmental laws, on the states’ addressing the concerns of minority communities and the emission exposures in those communities, as part of their permitting processes.

Federal agencies should require state and local zoning and land-use authorities, as a condition for receiving and continuing to receive federal funding, to incorporate and implement the principles of environmental justice in their zoning and land-use policies. This approach would start to address the disparity in the distribution of environmental and health burdens.

Federal agencies should use their current authority to withdraw funding to states that fail to enforce environmental laws adequately.

Thirteen years later, the problems in Waukegan, Uniontown, and Flint show that people in these poor black and Latino communities are still being ignored.

NEXT STORY: Former Denver Mayor Regrets ‘Mile High’ Decision