Immigration: Down in Farm Country, Up in Some Cities

Connecting state and local government leaders

Many high-tech centers, like Seattle, are seeing more immigration than they did 10 years ago. At the same time, a drop in immigration to rural agricultural counties has led to critical farm labor shortages.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Tim Henderson.

SEATTLE — In the fruit and vegetable country around Seattle, farmworkers talk about smuggling fees as high as $8,500 per person and arduous, circuitous routes across the Mexican border. Under those conditions, thousands fewer are coming to work in the fields and farmers are desperate for more help.

But in Seattle, it’s the opposite: more immigrants are flocking to fill a void in fields like information technology and engineering, as tech giants like Amazon and Microsoft expand operations. Many are from India, with visas for skilled workers.

The divergent immigration patterns are particularly evident in Washington state, where farmland surrounds the booming tech centers of Seattle and nearby Redmond, home to Amazon and Microsoft. But the changes are occurring in other parts of the country, as Asians replace Mexicans in the immigrant stream.

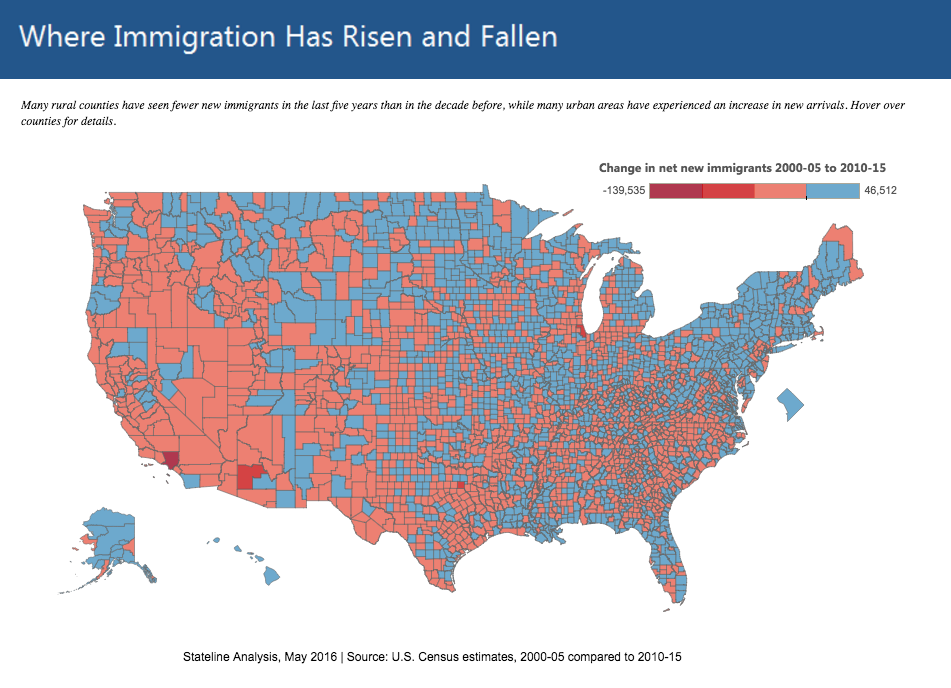

A Stateline analysis of Census estimates shows that many high-tech centers, such as Seattle, San Diego and Boston, are seeing more immigration than they did 10 years ago. At the same time, many rural agricultural counties that have relied on foreign migrant workers, primarily from Mexico, have seen a drop in immigration.

Agricultural areas from Georgia’s Hall County, home of poultry farms and processing plants, to Seward County, Kansas, home of cattle feedlots and packing plants, and Tulare County, California, which has fruit, vegetable and dairy farms, saw immigration drop more than 75 percent in the first five years of this decade compared to 2000 to 2005, when Mexican immigration was at its peak.

Indiana’s Elkhart County, where small farms and recreational vehicle manufacturing provide jobs, immigration dropped from a total of almost 5,000 in the early period to less than 700. At the same time in the same state, it grew by 64 percent in Tippecanoe County, home of Purdue University, and more than doubled in Monroe County, home of Indiana University.

Among the 10 counties with the biggest immigration gains in this decade are tech or education strongholds like Seattle’s King County, San Diego County, and Boston’s neighboring Middlesex County, home of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University.

The dramatic shift in immigration has implications for state and local economies. Tech companies say the newcomers fill a gap in U.S.-born science and technology graduates, allowing them to keep more operations in the U.S. and create jobs for other Americans. Farmers and their advocates say the shortage of migrant workers forces them to cut production, waste crops they can’t harvest or pay more for labor, which opens the door to less-expensive foreign produce.

“Here in Washington, we do hand-picked crops,” said Burr Mosby, who has a 350-acre vegetable farm in the Green River Valley southeast of Seattle. “We need workers. And we can’t get them,” he said.

In 11 rural counties around Seattle, the number of immigrants in the first half of this decade was between half and 90 percent less than what it was in 2000-2005.

“Farmers are in a very dire position here, locally, statewide in Washington, on the West Coast — anywhere in the country where there’s labor-intensive agriculture,” said Chad Kruger, director of Washington State University’s Northwestern Washington Research and Extension Center in the Skagit Valley north of Seattle. “The cost of production has gone up and they are struggling to get the labor they need.”

But in King County, more than 75,000 new immigrants arrived between 2010 and 2015, an increase of 24 percent over the previous decade. The number of immigrants arriving from India more than doubled between 2005 and 2014, and the number from China grew more than 50 percent. Immigration also was up in neighboring Pierce and Snohomish counties, where many workers are finding homes as King County home prices and rents rise in the tech boom.

“The tech factor is really driving up South Indian immigration, not only in Seattle but in the suburbs,” said Shelly Kamran, a Seattle-born daughter of Indian immigrants who organizes social events for new South Asian immigrants.

The new immigrants are changing the city in many ways. Two Indian immigrants were recently elected to public office in Seattle: Democratic state Sen. Pramila Jayapal in 2014 and city council member Kshama Sawant in 2013.

And A.R. Rahman, the singer and musician who composed the soundtrack for the movie “Slumdog Millionaire,” sold out a 5,000-seat show in Redmond last year and added a second. “I couldn’t imagine this happening even five years ago,” Kamran said.

Farmworker Exodus

Border crackdowns are causing Mexican laborers to think twice about coming to work in the U.S. Mexican fertility rates also are dropping. For these and other reasons, there has been a sharp decline in the unauthorized population of Mexicans in the U.S, from 6.9 million in 2007 to 5.6 million in 2014.

There are almost daily reports of people being turned back or detained at the border, either trying to get in for the first time or returning from family visits, said Maru Mora, an unauthorized immigrant who volunteers at her Latino Advocacy office north of Seattle to help others find legal help. “People don’t migrate the way they used to,” Mora said. “They don’t move back and forth to Mexico like before.”

Family unity is the main reason an increasing number of Mexicans are returning home, which contributes to the dearth of workers, according to a Pew Research Center report last year (The Pew Charitable Trusts funds the Pew Research Center and Stateline).

The number of new field and crop workers immigrating to the U.S. fell by roughly 75 percent between 2002 and 2012, according to a report last year by the Partnership for a New American Economy, a coalition of business leaders and mayors seeking immigration reform.

California was particularly hard hit by the farm labor shortage. But Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina collectively lost one in four crop workers between 2002 and 2014, while Colorado, Nevada and Utah lost more than a third of their crop workers, most of whom are immigrants.

Without those shortages, farms could have produced another $3.1 billion in crops annually, the Partnership for a New American Economy report concluded. Farmers have adopted strategies to reduce labor, including switching from grapes and peaches to mechanically harvested almonds and walnuts, according to a 2014 report by the University of California’s Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics.

Imports of fresh fruit and vegetables are growing. The Partnership for a New American Economy blames it on a lack of immigrant labor, which has forced U.S. farmers to abandon healthy crops even during recent years of drought. “Farmers don’t have the labor they need to expand their operations and keep pace with rising demand,” their 2015 report said.

Mosby, the Green River Valley farmer, said he used to rely on immigrants who simply showed up when it was time to do the work. Now he works 90-hour weeks and still can’t get all his cucumbers, beets and squash picked, leaving much of it to go to waste. “It fries my hide that there are people on the border wanting to work and they can’t get over [the border],” he said.

In theory, farmers like Mosby could use temporary visas meant for farmworkers. The government issued 108,000 of the H-2A visas last year, more than triple the 32,000 issued in 2005. But he would have to pay to transport workers and manage housing for them, which would raise his expenses and likely make other workers demand the same benefits, Mosby said.

The visa program is cumbersome and expensive, said Robert Guenther, senior vice president for public policy at the United Fresh Produce Association, a trade group. California and Washington state are among the hardest hit by the labor shortage, he said, but it is an issue all over the country, including on apple farms in New York and Michigan.

Liz Elwood Ponce, whose farm ships strawberry plants from northern California to growers farther south for finishing and harvesting, needs hundreds of people to tend the plants and ready them for shipping in barrels.

“They used to just show up at the right time,” she said of Mexican migrant laborers. Since they disappeared, the farm is looking at more automation. But much of the work, like stripping sod from plant roots for shipping, requires people.

“It’s hard to replace the human hand,” Elwood Ponce said. “It’s just getting harder and harder for us to find people because it’s harder for them to travel from Mexico all the way up here.”

Demand for Tech Workers

Demand for special visas for high-skilled workers has grown since the tech boom started up again in the late 2000s. In recent years, applications for the H-1Bs have exceeded the number available, forcing a lottery to allocate them.

U.S. State Department records show people from India got 69 percent of the nearly 173, 000 H-1B visas issued last year, with 11 percent going to people from China. The number of visas is up 40 percent since 2005.

Critics like Hal Salzman, a professor of public policy at Rutgers University, complain that the program has flattened wages in tech and led to more layoffs, even at well-funded startups, because H-1B workers have been used by staffing companies to replace higher-paid information technology employees in some cases.

“These are policies that deny U.S. workers — whether native or immigrant, whether citizen or permanent resident — the career and compensation their education and skills should bring them,” Salzman testified to the Senate Judiciary Committee in February.

But advocates for the program say the educated H-1B workforce can create more jobs for all workers by keeping the tech industry rolling. States that gained the most such jobs in recent years are California, New Jersey, Texas, New York and Illinois, a separate report from the partnership last year concluded.

The San Diego-based technology firm Qualcomm called for more H-1B visas last year, saying the program helped it keep operations in the United States that would otherwise have to move overseas because of shortages of engineers and other technical workers. Immigration in San Diego County jumped 45 percent to almost 85,000 in the last 10 years.

Immigrants arriving on the visas are behind some of the rise in immigration in King County. The increase in Seattle and its suburbs helped propel the state as a whole to gain more than 9,000 immigrants in this decade compared to the early 2000s, despite immigration losses as high as 90 percent or more in agricultural areas like Yakima County and Grant County.

The newest wave is joining a complex array of immigrants in King County, which includes Seattle and 38 other cities and towns, said Chandler Felt, the county’s demographer.

More than 130 languages are spoken in the county, ballots in Spanish and Korean were added this year to those provided in Chinese and Vietnamese, and Seattle offers web pages in Hindi and several other languages.

New private schools have opened in the area stressing Hindi and Chinese language instruction for children of immigrants.

“Immigrants don’t mind moving here because it’s a very welcoming place for them,” Felt said.

NEXT STORY: Denver takes on regional homelessness with tech