An All-In Response to the Opioid Crisis

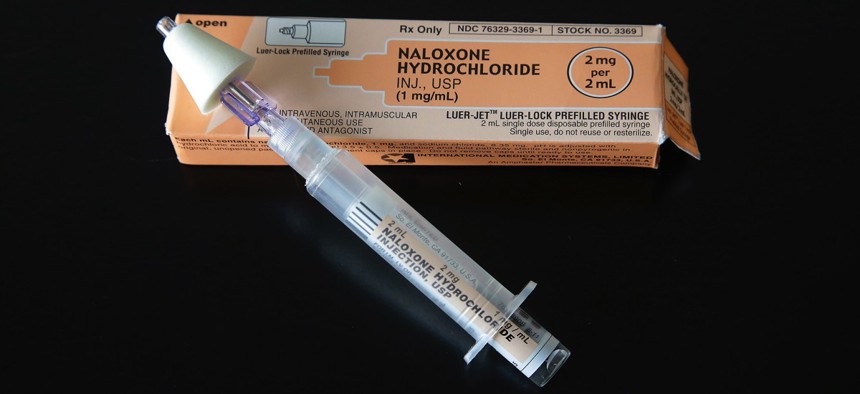

A nasal administered dose of Narcan, a drug that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose. (AP Photo/Stephan Savoia)

Connecting state and local government leaders

This city of 50,000 on the Ohio River has the highest drug overdose death rate in a state ranked No. 1 in the nation for overdose deaths.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Christine Vestal.

HUNTINGTON, W.Va. — The high school students who lined up to graduate at the civic center here on a recent afternoon celebrated their bright futures. And for the college students in shorts and flip flops who filled the downtown cafes and shops, life seemed pretty good, too.

But for the 30-something heroin addicts who packed the waiting room of the local health department just a few blocks away, the future doesn’t look as promising.

By its own calculations, this city of 50,000 on the Ohio River has the highest drug overdose death rate in a state ranked No. 1 in the nation for overdose deaths. The city’s overdose death rate, at 119 per 100,000 last year, is nearly 10 times the national rate.

It’s not a statistic that Huntington advertises in tourist brochures or welcome packages for students attending the local college, Marshall University. But Mayor Steve Williams said the worsening heroin problem was becoming so plain to everyone that “we had to define it, before it defined us.”

And so, with some state and federal lawmakers backing him up, the city’s law enforcement and public health leaders, along with education, business and religious groups, joined forces in 2014 to attack the problem. By August 2015, Williams had created a detailed strategic plan for defeating the epidemic and an Office of Drug Control Policy to oversee it.

The Police Department started trying to divert drug users to treatment rather than jail. The city launched an innovative program for babies born to women who used opioids during pregnancy, and opened a drug court for women charged with prostitution. There’s also a new school-based program for kids whose parents are arrested for drug crimes.

But the most visible, and controversial, of Huntington’s responses to its surging opioid epidemic so far is a needle exchange program, the first in West Virginia and one of only a handful in the heart of Appalachia, the 13-state region hardest hit by the opioid epidemic.

Every Wednesday, addicts gather in a brightly lit waiting room, seeking clean needles and other services that might reduce the health risks of their intravenous drug use. It won’t necessarily change their lives, but it could reduce the harm that comes with a life of drug addiction.

Surrounding the Problem

A once prosperous railroad center where Kentucky and Ohio meet West Virginia, Huntington is a microcosm of the nation’s decades-long struggle with prescription pain pills and heroin. The target of profiteering doctors who overprescribed addictive pain medicines for cash and drug dealers who rushed in with heroin when the pill supply dwindled, Huntington mainly fought back with law enforcement tactics.

But, as in much of the rest of the country, Huntington’s leaders realized they couldn’t arrest their way out of the drug problem. “For every drug dealer we took off the street, three more showed up,” said Jim Johnson, Huntington’s former police chief who is now Williams’ director of drug control policy.

The first needle exchange programs in the U.S. were developed in the mid-1980s to stem the spread of AIDS. They provide sterile supplies for injection to drug users in exchange for used needles to stanch the spread of infectious diseases and help prevent other health hazards, such as skin abscesses and infections of the veins, heart and other organs.

The programs have been shown to save millions in health care costs for drug users and reduce the risk to the public of accidentally getting stuck by a discarded needle.

But opponents have argued that providing free IV injection supplies only makes it easier for drug users to maintain their habit. And the programs have been difficult, if not impossible, to get started in politically conservative regions like Appalachia.

The enormity of the nation’s ongoing opioid epidemic, which killed more than 28,000 in 2014, and high-profile support from the Obama administration over the past year, has muted some of those critics. In January, Congress ended a nearly 30-year ban on federal funding for the programs.

Still, Johnson said he was shocked to find himself kicking down doors to get the money to pay for a needle exchange program.

“It made so much sense,” he said. “It was relatively cheap to stand up and would save hundreds of millions in health care costs over the next decade. It was something we could grab ahold of.”

Early results show the needle exchange program, and Huntington’s other recent efforts, may have made some headway: Overdose deaths were down by 40 percent in the first quarter of 2016, compared to the same period last year. But, Johnson cautioned, “We’ve been disappointed before.”

Harm Reduction

Like the roughly 200 other cities with needle exchanges, mostly on the East and West coasts, the Cabell-Huntington Harm Reduction and Needle Exchange Program provides needles, syringes and sterile water, cotton filters, heroin cookers and alcohol swabs at no charge. The staff throws condoms into patients’ to-go bags, for good measure.

Since it opened its doors in September, the weekly clinic has also offered free screening for HIV, hepatitis and sexually transmitted diseases, as well as pregnancy tests, contraceptive services and first aid for wounds. Drug users also are encouraged to avail themselves of the Huntington-Cabell Health Department’s other services, including primary care and chronic disease management.

What’s remarkable about Huntington’s program is how quickly it built up a large following, said Daniel Raymond, policy director for the Harm Reduction Coalition, a New York-based organization that advocates for syringe exchanges and other protections for drug users.

In just nine months, the program has had nearly 4,000 visits; it averages 150 visitors a week.

Late one recent Wednesday morning, armed police officers paced around the lobby as about 45 people, mostly suntanned and tattooed, waited for their names to be called. Dr. Michael Kilkenny, the health department’s medical director, said heroin users are prone to getting into small scraps, but they are rarely violent, and his patients say the guards make them feel secure.

The needle exchange program aims to curtail the spread of new cases of hepatitis B and C, both of which shot up in Huntington over the last five years, in tandem with the surge in heroin use. But it’s also designed to lower the death toll by teaching drug users how to rescue fellow users by administering naloxone, which can reverse a potentially lethal overdose.

Every Wednesday at the clinic, a pharmacist trains patients on how to administer naloxone, once in the morning and once in the afternoon. After that, they can take home a one-piece injector called EVZIO that includes audio instructions and can be administered through a person’s clothing. (The clinic’s inventory of 2,200 injectors, valued at $1.5 million, was donated by the manufacturer, Kaléo.)

Distribution of naloxone, along with West Virginia’s 2015 “good Samaritan” law, which allows people to call 911 to report an overdose without risking arrest, has resulted in an increase in the number of 911 overdose calls and a decline in overdose deaths, Kilkenny said.

A Portal to Recovery

Krista Spears, a bubbly 35-year-old, has been a regular at Huntington’s syringe exchange program since it opened. She has advanced hepatitis C and doesn’t want to spread it to any of her fellow drug users, she said. When she’s ready to quit heroin, she plans to use her Medicaid coverage to get treatment for her hepatitis. But she’s not ready yet.

Like many longtime drug users, Spears has tried to quit before and doesn’t want to set herself up for failure. “Of course I want to quit,” she said. “No one wants to be addicted. But there’s no use trying until I’m ready.”

For those who are ready, Huntington’s syringe exchange gives patients the opportunity to talk to a recovery coach — a peer who is in recovery from addiction and can walk them through the process and help them get started.

“For Huntington to build the recovery coach role into its program is innovative and exciting,” Raymond said. It represents a new wave in needle exchange programs.

Spears started using prescription pain pills when she was 14. She took her mother’s Percocet and OxyContin out of the medicine cabinet and got high all the time. “She had so many, she never missed them,” Spears said.

That’s a typical story, Kilkenny said. The average age of people coming to the clinic is 36, he said, and most started using painkillers and other drugs when they were between 13 and 18, he said. That means the problem started 18 to 20 years ago, when West Virginia and other Appalachian states were flooded with liberally prescribed opioid pain medications.

Once states started clamping down on prescription pain medicine, many people turned to heroin. Today, Huntington is one of the easiest places to buy it. Spears said the first day she arrived in the city a dealer approached her on the sidewalk and asked if she wanted to get high. Now, she said, her drug habit costs about $20 per day, not much more than a heavy smoking habit.

“Our drug dealers come from Detroit,” Johnson said “The price of heroin there is half the price they can sell it for here.” With an estimated 7,000 Huntington residents addicted to opioids, about 14 percent of the population, the city represents a thriving market. “They call us Moneyton,” he said.

Kilkenny knows that the only way to trim Huntington’s surging demand for heroin is to reduce the number of people who are addicted to it by getting more people into treatment.

The mayor’s strategic plan called the needle exchange a “portal to recovery.” As the health department builds trust within the drug-using community, people like Spears will know where to turn when they decide to quit.

But Kilkenny and others say there is a dire shortage of treatment in Huntington and surrounding Cabell County, particularly medication-assisted addiction treatment using one of the three federally approved medicines — methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone.

“People are begging for treatment and can’t get it,” Kilkenny said. As long as the shortage persists, “we’re going to be in the business of clean needles,” he said. “We’re really in a holding pattern.”

NEXT STORY: State Health Care Costs Vary Significantly