Prisons, Policing at Forefront of State Criminal Justice Action

Connecting state and local government leaders

In 2016 some states moved to reduce their prison populations while others focused on supporting offenders once they return to their communities and revamping the way police departments interact with the public.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Sarah Breitenbach.

Faced with overcrowded prisons and evidence that lengthy sentences don’t deter crime, more states opted this year to revamp sentencing laws and send some people convicted of lesser, nonviolent crimes to local jails, if they’re locked up at all.

In an about-face after a half-century of criminal justice policies that favored long-term incarceration, Alaska, Kansas and Maryland this year joined at least 25 other states in reducing sentences or keeping some offenders out of prison.

The move to end lengthy prison stays for low-level offenders is one of several steps states took this year in reevaluating criminal justice policies during legislative sessions that have wrapped up in all but a few places. Other measures would help offenders transition back into their communities after release and hold police more accountable.

For years, many lawmakers were wary of appearing soft on crime. But states have recently retooled their criminal justice policies in response to tight post-recession budgets, shifting public opinion and court rulings demanding they ease prison overcrowding.

“For a long time, the fact that America had more people in prison than anywhere else in the world wasn’t something that we were acutely aware of or embarrassed by,” said Tim Young, the top public defender in Ohio, where a group of legal, criminal justice and public safety officials and experts are rewriting the state’s criminal code.

But today, public and political perspectives on the usefulness of incarceration, especially for minor crimes, are changing, said Young, the vice chairman of the group.

“We have potentially thousands of people in prison who shouldn’t be there and we’re actually harming public safety by locking up low-risk, low-level felons,” Young said.

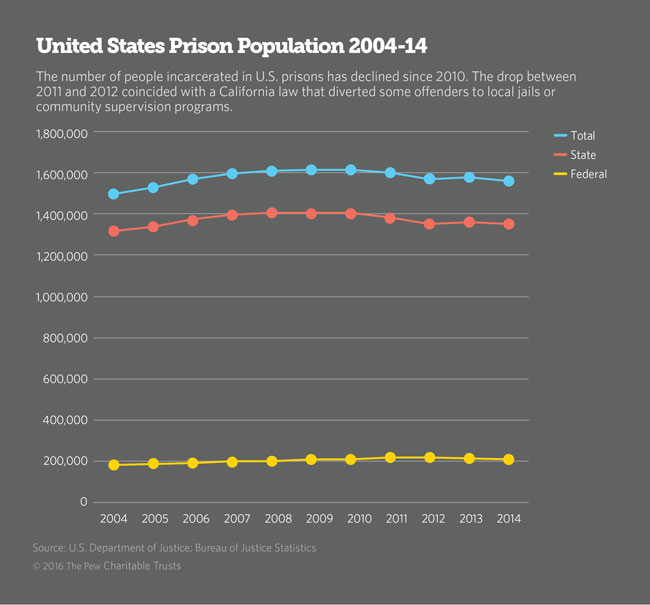

States are already seeing results from this shift in thinking. The number of state and federal prisoners dropped by 28,600 between 2011 and 2012 after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that overcrowding violated prisoners’ rights to physical and mental health care, and California began diverting nonviolent offenders to serve their sentences in local jails and under community supervision. Between 2013 and 2014, the population in state prisons alone declined by more than 10,000 people, to 1.35 million.

Criminal justice reform advocates in California are hoping to capitalize on that change in public opinion. They’re supporting a ballot measure that would shift authority to transfer juveniles into the adult court system away from prosecutors to judges, allow prisoners to receive earlier consideration for parole, and establish new regulations to award time-served credits to people who have completed rehabilitation and education programs.

“We see everyday people recognizing that we spend too much money on prisons and that they’re ineffective and it’s really time to do something different,” said Lenore Anderson, director of Californians for Safety and Justice, which is leading the ballot initiative campaign. Signatures to put the measure on the November general election ballot are being verified.

Alaska, Maryland and Kansas passed bills this year that divert all shoplifting and first-time DUI offenders away from prison, eliminate mandatory minimum sentences for low-level drug offenders, expand parole eligibility, and establish diversion programs for youth offenders, respectively. (Those states worked with The Pew Charitable Trusts to write their new laws. Pew also funds Stateline.)

And in Tennessee, lawmakers changed standards for property theft charges to help reduce the prison population, and established alternatives to re-incarceration for offenders who violate conditions of their parole or probation.

Many of the proposals enacted this year strike a complicated balance between boosting support for ex-offenders and ensuring that those convicted of crimes are held accountable.

Relaxing sentencing and increasing the amount of good-time credits prisoners can earn toward an early release means hardened criminals might get out of prison sooner than they should, said Maryland Del. John Cluster, a retired police officer.

But he said his state could have gone farther to help offenders with job training and other re-entry assistance once they serve their time.

“You clean an addict up and you let him out,” Cluster, a Republican, said. “[If] he doesn’t have a job, in less than a year he’s going to be back on the drugs.”

Many lawmakers are eager to reduce the expenses that come with running prisons. For example, prison systems cost taxpayers 14 percent more than state budgets indicate because they do not factor in expenses like benefits for correctional employees and hospital care for inmates. Prisons also strain local social services, child welfare and education programs.

But still, some elected officials want to build more.

In Alabama, Republican Gov. Robert Bentley proposed spending $80 million to consolidate some of the state’s existing prisons and build four new ones. The state has one of the most overcrowded prison systems in the country, operating at 180 percent of capacity.

The proposal was billed as a way to reduce overcrowding, improve the safety of staff and inmates, and pave the way for better rehabilitation and re-entry programs. But Lisa Graybill with the Southern Poverty Law Center, who helped defeat the proposal, said the state should wait to see the effect of sweeping changes to state sentencing laws enacted last year.

The changes are expected to reduce the state’s prison population — 32,000 in 2014 — by more than 4,200 by strengthening community supervision and prioritizing prison beds for violent criminals.

“Let’s analyze what other sentencing reforms we could make that might further reduce our capacity without necessitating expansion,” Graybill said.

Re-entry Efforts

Several states moved to help ensure fewer offenders end up back in prison after they are released.

A new Georgia law aims to help people re-entering their communities to stay out of prison by removing a lifetime ban on food stamps for drug felons and expanding the state’s “ban the box” law, which keeps the state from asking applicants for public jobs to indicate whether they have a criminal record.

Advocates of banning the box say having to fess up to a criminal conviction early in the hiring process disqualifies many capable applicants before they can be interviewed, regardless of how dated or minor their record may be. But business groups argue the law makes it difficult to screen job candidates and puts their establishments at risk for theft.

Already 100 cities and counties and 24 states have passed “ban the box” legislation, according to the National Employment Law Project. Similar laws were proposed in at least three states — Kentucky, Louisiana and West Virginia — this year, though none passed.

Police Accountability

States also continued to revamp policing policies this year, an effort largely born of public outcry following several high-profile deaths that involved police officers in 2014 and 2015.

Many have turned to body cameras to document police interaction with the public and pursue cases of misconduct, though concerns remain about when the cameras should be used and who can access their footage. A May 2016 study from the European Journal of Criminology found that the cameras do not reduce police use of force.

Only four states had body camera laws before 2015. Now 25 states have passed laws to regulate the devices. This year four states — Florida, Indiana, Utah and Washington — and the District of Columbia enacted new body camera laws.

Outcry over police-community relations led the White House to form the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which issued 59 recommendations for states and local police departments last spring.

Suggestions for law enforcement focused on six areas — building community trust, establishing policing policies that reflect local values, using social media and technology to engage with citizens, working with neighborhoods to enhance public safety, training officers to handle various crisis situations, and focusing on officer health and safety.

Laurie Robinson, a George Mason University professor and former Justice Department official who co-chaired the group of police officers, academics and social justice advocates, predicted policing reforms will be slow to occur, and will rely more on cultural shifts within police departments than legislation.

“A good deal of training currently for young recruits is, not surprisingly, around how to shoot a gun, how to drive and much less about communication skills,” she said. “And yet so much of their job is about dealing with people.”

NEXT STORY: Groundwork for a Connected Vehicle Pilot Program in Tampa Forges Ahead