Shrinking Small Towns See Hope in Refugees

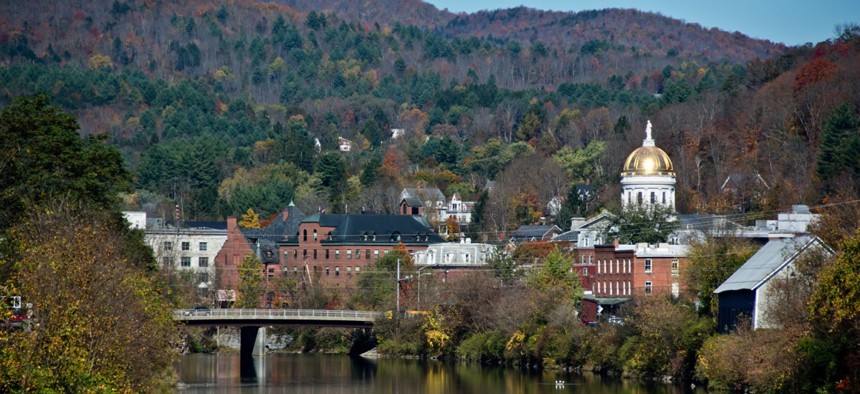

Montpelier, Vermont.

Connecting state and local government leaders

Some small cities and towns across the country see the new arrivals as a way to boost shrinking populations and improve sagging economies.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Tim Henderson.

RUTLAND, Vermont — Mayor Christopher Louras sees trouble ahead for this small city of about 16,000 at the foot of the Green Mountains.

“It’s a strong, vibrant community but unless we do something to stem the population decline, we’re going to be in big, big trouble,” Louras said. “And it’s not just Rutland. Rutland is a microcosm of the state and small towns around the country.”

But the mayor sees a quick fix. He’s asked Vermont’s resettlement agency to send refugees to Rutland, and says they would help fill vacant housing and entry-level jobs to keep the economy moving.

It’s an approach small towns from Montana to Georgia are increasingly considering as they grapple with shrinking and aging populations.

The mayors of Central Falls, Rhode Island; Clarkston, Georgia; and Haledon, New Jersey, joined big-city mayors last year in signing a letter saying they had accepted Syrian refugees and would take more. And as some governors and members of Congress called for a halt to the arrival of refugees from Syria, the mayors of Normal, Urbana and Evanston in Illinois; Socorro, Texas; and Clearfield City, Utah, signed aletter that noted “the importance of continuing to welcome refugees to our country and to our cities.”

Few refugees have resettled in Montana since 1991. But with Missoula Mayor John Engen’s support, a branch of the International Rescue Committee opened its doors and the group has arranged to help settle 100 Congolese refugees, who are expected to start arriving this month.

The decision to seek refugees, especially Muslims from Syria, can be a political lightning rod. The mayor of Sandpoint, Idaho — population 7,800 — proposed welcoming Syrian refugees when he was sworn in, in January, but withdrew the idea the same month after raucous protests.

But there’s a growing sense among local officials, especially in small towns, that refugees have something to offer the economy, said Eskinder Negash, a former director of the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement.

“Every time a refugee rents an apartment, every time a refugee shops for food, there’s some income coming in for the city and going into the tax base,” said Negash, now a senior vice president of the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI), a network of groups that help resettle refugees around the country. “There’s a new realization that refugees can be an economic engine for some of these small communities.”

Reversing the Losses

Small towns and rural areas across the U.S. have been losing population since 2010, though the losses have shrunk to 4,000 a year in 2015 from an average of 33,000 a year earlier in the decade, according to a May report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

But in many areas, refugees have helped to offset or reverse the losses.

About 350 refugees settled in Fargo, North Dakota, last year, mostly from Somalia, Iraq and Bhutan. And they have contributed to strong population and economic growth, said Fargo’s mayor, Dr. Tim Mahoney.

“Our refugees have come in and brought a lot to our community,” Mahoney said. “They opened a mosque, and people came in and said, ‘Oh, this is just like a Lutheran social. There’s food.’ ”

The refugees also made the city more diverse, Mahoney said, with the non-white population growing from 2 to 11 percent since 2002.

“Our priority is to be a welcoming city and continue to grow in that manner,” Mahoney said.

In Clarkston, Mayor Ted Terry, a Democrat, said you can read the history of world conflict in the city’s refugee population. There are Vietnamese, many now elderly, who came in the wake of the Vietnam War; Ethiopians, Eritreans, Somalis, Sudanese, Bosnians, Bhutanese and Burmese, who started arriving in the ’90s; more recent arrivals from Afghanistan and Iraq; and Syrians, who began to arrive last year. Many of the refugees have found jobs in chicken plants, where Mexican immigrants used to work.

Terry, who said he has personally provided one Syrian family with furniture and clothes, said there’s always some controversy about refugees. “One school of thought [among residents] is that we don’t have room for them,” Terry said. “To that I tell people, ‘What if they weren’t here? All these apartments would be vacant, and vacant apartments lead to crime. They are very peaceful, hardworking people.’ ”

About 70,000 refugees were resettled in the United States last year. Iraq and Burma were the largest sources of refugees, with a combined 31,000 people. About 1,700 were from Syria; the Obama administration announced last year it wants to ramp the number up to 10,000 this year.

Controversy in Rutland

Across Vermont, a shrinking and aging population, low unemployment, and a struggle to find workers are hindering economic progress, according to a report this year by the Vermont Chamber Foundation’s Vermont Futures initiative. “Vermont will need to find a way to attract and retain qualified workers,” another report found.

Rutland has lost more than 100 people every year this decade, according to census estimates.

The median age in Rutland County is 46.2, up from 44.3 in 2010 and more than eight years above the national median age of 37.8 last year.

Unemployment was 3.6 percent in the area as of May, which Louras said was too low. (The national rate was 4.7 percent and Vermont’s was 3.1 percent.) And local businesses say they have a hard time recruiting entry-level workers.

“We don’t have enough employees,” said Tyler Richardson, an assistant director of the Rutland Economic Development Corporation. “There’s a desperation as to what’s the next step, how to attract people to this region, how we fill these positions.”

Louras says refugee families would help fill vacant housing and entry-level jobs, and provide more diversity that could help attract young families to an aging, overwhelmingly white community.

After considering other cities in the state, the Vermont Refugee Resettlement Program, the local affiliate of the USCRI, recommended that 100 Syrian refugees be sent to Rutland. The group is awaiting approval from the U.S. State Department and the refugees could begin to arrive in November, said Stacie Blake, director of government and community relations for USCRI.

A volunteer organization, Rutland Welcomes, has sprung up, with more than 700 volunteers who have broken into committees to learn Arabic and plan for welcoming and cultural exchange events, said Marsha Cassel, a high school French teacher who is part of the volunteer group’s informal leadership.

But not everyone in town agrees that refugees are the answer.

Seven of the 11 members on the Rutland Board of Aldermen signed a letter asking the State Department not to send refugees. One of them, Edward Larson, said he wants more background checks and thinks the mayor should have asked the board before proceeding on his own.

“I believe the mayor was wrong in his actions albeit his intentions were good,” Larson said.

Valerie Fusco, 76, has lived in the area since she was 9 years old and raised three children who did well in Rutland as a barber, a salesman and a nurse. But that was the last generation that stayed here, she said.

“The young couples, if they’re lucky, go to college and move on because there’s nothing here for them. Where are the jobs we’re going to give these new people? I have nothing against them but we should take care of our own first,” Fusco said.

But several employers said they would welcome the new arrivals.

The area’s largest employer is Rutland Regional Medical Center, with about 1,600 employees. Its president, Tom Huebner, said that of the hospital’s 140 job openings, some could be filled by refugees, especially in housekeeping and food service. Ursula Hirschmann, a German immigrant who owns a fast-growing custom windows business in Rutland, said she would hire refugees in entry-level jobs like sanding and assembly.

New Life and Energy

Small towns don’t always have to actively seek refugees. Around 2000, Lewiston, Maine, found itself a preferred destination for Somali Bantu refugees who were initially relocated in more urban areas around the country.

“They were searching for something that felt a little smaller and more intimate, a little more manageable,” said Catherine Besteman, an anthropology professor at Colby College who has written about the Lewiston refugees.

Alarmed by the pace of arrivals, then-mayor Laurier Raymond Jr. wrote a letter in 2002 asking Somalis to stop coming, sparking demonstrations and counter-demonstrations. But a subsequent mayor, Larry Gilbert, said at a U.S. Senate hearing in 2011 that the Somalis had brought “new life and energy” to Lewiston. Besteman agreed.

“Lisbon Street [in Lewiston] had a lot of empty storefronts, and now it’s full of Somali cafes, translation agencies, a mosque,” Besteman said. “People think of large urban areas when they think of immigration and refugees, but I think small towns may be where we should be looking.”

NEXT STORY: German Official Feels Slighted and Neglected by U.S. Sister City in Michigan