The State and Local Regulatory Predicament Middle-Market Companies Face

In a survey, many company executives find complex regulations manageable, but that doesn't mean government agencies can't make their lives easier to encourage economic development.

Most middle-market companies find their regulatory burden manageably high and local officials more knowledgeable than state and especially federal officials, according to a recent National Center for the Middle Market report.

NCMM defines the middle market as the middle third of the private sector based on overall employment and revenue—roughly 200,000 companies making between $10 million and $1 billion a year.

A survey of their executives, “Middle Market Perspectives on Government Services,” found 78 percent felt local regulation on business had some sort of impact, compared to 87 percent for state regulations and 89 percent for federal.

“State and local government officials should recognize that they do have an impact, and it can be positive or negative,” Tom Stewart, NCMM's executive director, said in an interview. “As they think about the work they do, they should very much think about its impact on midsize companies because the data show this is where the growth is. This is where the jobs are; the jobs come from helping the companies already in town grow.”

At the federal level, the Occupational Safety and Health Act, Affordable Care Act, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and environmental regulations all contribute to the middle market’s regulatory burden. Still, 51 percent of executives surveyed felt that high burden, when compounded with state and local regulations as well, was manageable.

Meanwhile, 13 percent of middle market executives felt regulations are unmanageably high.

Middle-market companies are often large enough to be in multiple cities, if not states, but lack the resources for a huge compliance staff that can easily account for differing local sales taxes between jurisdictions, Stewart said. And compliance isn’t optional.

Some work through industry organizations and chambers of commerce to make officials better understand their predicament.

“In many cases, government civil servants are trying to do their jobs and don’t necessarily have the experience to understand the impact of what they’re trying to do, despite their good intentions,” Stewart said.

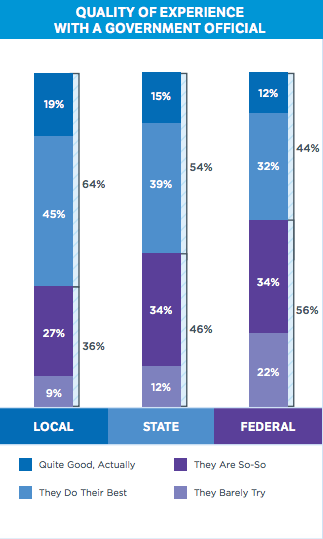

According to the survey, 64 percent of executives appreciated their interactions with local government officials, compared to 54 percent with state officials and 44 percent with federal officials.

Stewart speculates that could be because local regulations tend to be crafted to local circumstances, and local officials are easier to get ahold of and more flexible.

Middle-market companies are often in the unfortunate position of being too big to be exempt from government reporting requirements but too small to afford lobbyists capable of carving out an exemption.

“The midsize company is sort of like a guy who only has 1040 income and doesn’t itemize,” Stewart said.

Across all levels of government, middle-market executives would rather officials make taxes less complex than lower them, according to the report.

Stewart sees the findings as overall positive for state and local officials, so long as they keep in mind their middle-market constituencies and their potential for economic development.

Local governments should first focus on ensuring basic services like policing, sanitation and transportation are effective; then simply regulations while boosting incentives; and finally improve the business climate, he said.

“Officials should ask themselves, ‘How can we get what we need as a polity without overburdening people with nuisances?’” Stewart said. “Do we need another biotech incubator or a workforce development program.”

Dave Nyczepir is a News Editor at Government Executive's Route Fifty based in Washington D.C.

NEXT STORY: Flooding Adds to Louisiana’s Budget Woes; SE Colo. Struggles With Opioid Abuse